Finding drone laws and safety guidelines should be easy nowadays. But much of what you can find online is full of misinformation and half-truths.

If you don’t know how to separate fact from fiction, you put yourself at serious risk. You also endanger manned aircraft pilots and people on the ground.

This article debunks the top drone myths, helping you share the skies safely.

Key Takeaways

- Drone pilots often have misconceptions about visual contact between drones and manned aircraft.

- There is more to visual line of sight (VLOS) rules than simply seeing the drone.

- Drone pilots must maintain situational awareness, even within the 400-foot altitude limit.

Myth #1 – Manned Aircraft Cannot Fly below 500 Feet

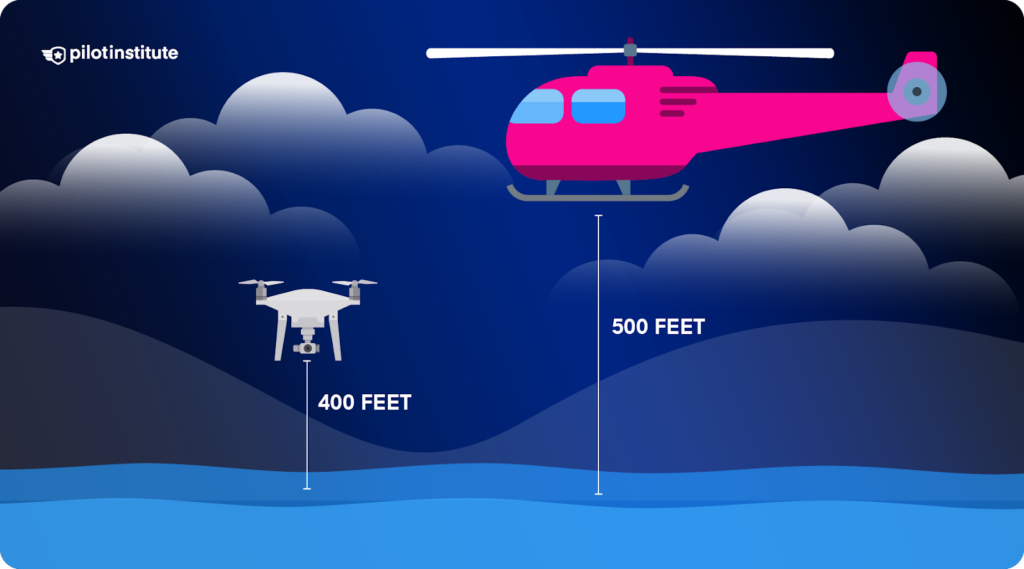

Under most conditions, the FAA allows drone flight up to 400 feet above the ground. This provides a safety margin between drones and higher-flying manned aircraft.

The FAA has established minimum safe altitudes for manned aircraft in 14 CFR § 91.119. Outside takeoff and landing, it might seem like the lowest altitude permitted is 500 feet. However, by looking closer, we see this isn’t the case.

For example, the 500-foot minimum altitude rule does not apply to helicopters. Unless situation-specific regulations state otherwise, they can fly lower. The only restriction is they must conduct the flight “without hazard to persons or property on the surface.” But if they can’t see your drone, they won’t be aware of the hazard.

It is common for helicopters to fly at low altitudes close to helicopter landing pads. This is true near hospitals, tourist areas, or large buildings with rooftop helipads. Emergency response or military helicopters also commonly operate at lower altitudes. For instance, Coast Guard helicopters can fly at low altitudes close to beaches.

How about fixed-wing manned aircraft? Generally, aircraft fly above 500 feet, but there are exceptions like pipeline patrol and crop spraying.

Also, the 500-foot rule doesn’t apply over open water or sparsely populated areas. In these areas, aircraft can fly as close to the surface as they deem safe. However, they may not fly closer than “500 feet to any person, vessel, vehicle, or structure.” But if you’re flying a drone in a sparsely populated area and the pilot doesn’t see it, it creates a collision risk.

What does this mean for drone pilots? You must be keenly aware of your surroundings, even if you fly your drone below the 400-foot limit. Are there nearby heliports, crop spraying operations, or hospitals? Make sure you know before you launch.

Myth #2 – Manned Aircraft Can See and Avoid Drones Easily

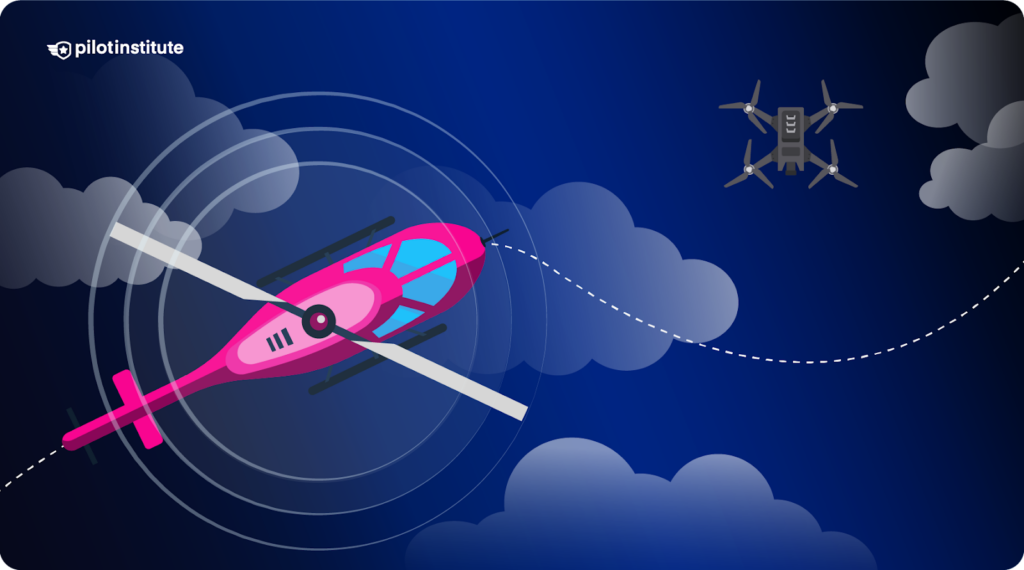

It’s tempting to think that aircraft pilots are always looking for drones. However, it is important to remember that they are often doing at least half a dozen other things at the same time.

The time available for spotting drones decreases as the pilot’s workload increases. Navigational tasks and aircraft configuration changes move their focus into the cockpit. Avoiding obstacles like wires and cables diverts the attention of low-flying helicopter crewmembers. These high-workload situations often coincide with low-altitude flight.

The ability to spot a drone from a manned aircraft varies from one pilot or situation to another. A study by Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University offers some insight. Helicopter pilots detect moving drones only 50% of the time at an average distance of 1,600 feet. The detection rate is much lower when the drone is static—only about 14%. The average detection distance is also much lower, at about 750 feet.

Let’s look at a real-world scenario. A helicopter pilot traveling at 100 KTAS has around 9.5 seconds to avoid a drone they spotted from 1,600 feet away. If the drone is stationary, that reaction time drops to a dangerous 4.5 seconds. Note that the numbers quoted here are average values. The detection distance can be much shorter, and helicopters often fly faster.

Another sobering data point comes from the FAA’s 2022 Advisory Circular 90-48E. It states pilots need 12.5 seconds to “identify, react, and avoid a midair collision.” In other words, pilots need to react immediately to avoid colliding with a moving drone. This relies on the pilot spotting the drone over a third of a mile away. It may be impossible to maneuver to avoid a stationary drone, even if spotted.

Myth #3 – UAS Pilots Can Easily See and Avoid Manned Aircraft

If an aircraft cannot easily spot your drone, can you, as a drone pilot, be trusted to yield the right of way to aircraft? This depends on your scanning technique, reaction time, and nearby visual obstructions.

We know the average reaction time for an aircraft pilot to see and avoid is 12.5 seconds. Drones are more maneuverable than manned aircraft, so we can shave 2 seconds off that time. Let’s assume that the manned aircraft is traveling at an average speed of 90 KTAS, or 152 feet per second. This gives a drone pilot a minimum detection range of 1,520 feet–almost a third of a mile.

However, 90 knots is quite slow, even for helicopters. Increased speed requires spotting the aircraft at a much greater distance.

If the aircraft is at an altitude of 300 feet, you need to be able to visually scan at an angle of 12 degrees over the horizon. This sounds simple but can get tricky quickly with obstacles like trees or buildings. You must maintain enough distance from obstacles to scan at the appropriate angle.

This point is not meant to discourage drone flight. However, it emphasizes the importance of situational awareness while flying a drone. As much as possible, fly with a visual observer. Fly in a spot that is clear of large obstacles. Maintain a distance from obstacles that ensures a clear view of your surroundings.

It’s also important to use the tools available to enhance situational awareness. A good example is using ADS-B data to monitor the nearby airspace for manned aircraft. Be aware that not all low-flying aircraft will show up on an ADS-B display. Also, check the airspace where you plan to fly. Don’t launch your drone before you do.

Myth #4 – As Long as You Can See the Drone, You Are Maintaining VLOS

Maintaining visual line of sight (VLOS) is one of the most important safety rules for drone flight. However, VLOS is more than just seeing the drone. According to the definition of VLSO in Part 107, it means four things:

- Know the unmanned aircraft’s location;

- Determine the unmanned aircraft’s attitude, altitude, and direction of flight;

- Observe the airspace for other air traffic or hazards; and

- Determine that the unmanned aircraft does not endanger the life or property of another.

If you cannot fulfill just one of these four items, you are not maintaining VLOS.

The fourth item is particularly tricky. If you fly too far away, your drone may endanger people or vehicles on the ground without your knowledge.

A point worth emphasizing is this: if you can only see your drone as a tiny speck in the sky, you are not maintaining VLOS. From that distance, it is impossible to tell your drone’s direction. You also cannot tell if you are flying over people.

Conclusion

The safety rules for drone operations exist because we are flying in shared airspace. We need to make sure our drones don’t put other aircraft, people, or property on the ground at risk.

Many drone flight myths come from believing we know more about our surroundings than we do. Knowing the facts is a great way to ground ourselves in reality. We must not overestimate our skills as drone pilots, especially in see-and-avoid situations.

Are you planning to fly your drone in busy areas? Read this article about what you need to do first.