-

Key Takeaways

-

What Is a Squall Line?

-

Formation of Squall Lines

- Squall Line Development Process

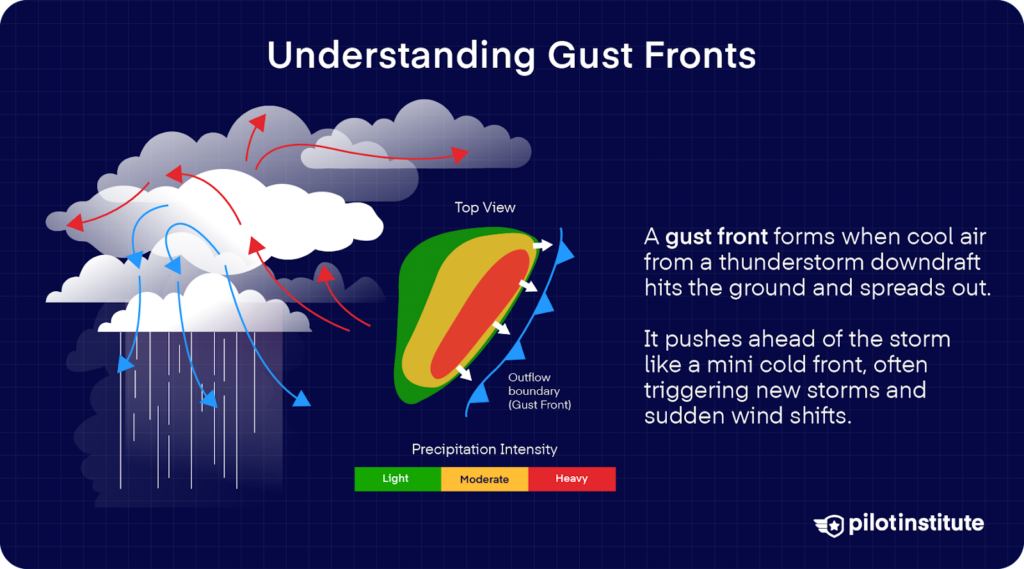

- Gust Fronts

-

Characteristics of Squall Lines

- Squall Line Duration and Movement

- Bow Echoes and Line Echo Wave Patterns (LEWPs)

-

Weather Hazards Associated with Squall Lines

- Downdrafts

- Heavy Rainfall and Flash Flooding

- Hail

- Lightning

- Tornadoes

-

How to Avoid Squall Lines

- Coordination with ATC

- Flight Planning Considerations

-

Can You Fly Through a Squall Line?

- Turbulence and Wind Shear

- Hail and Tornadoes

-

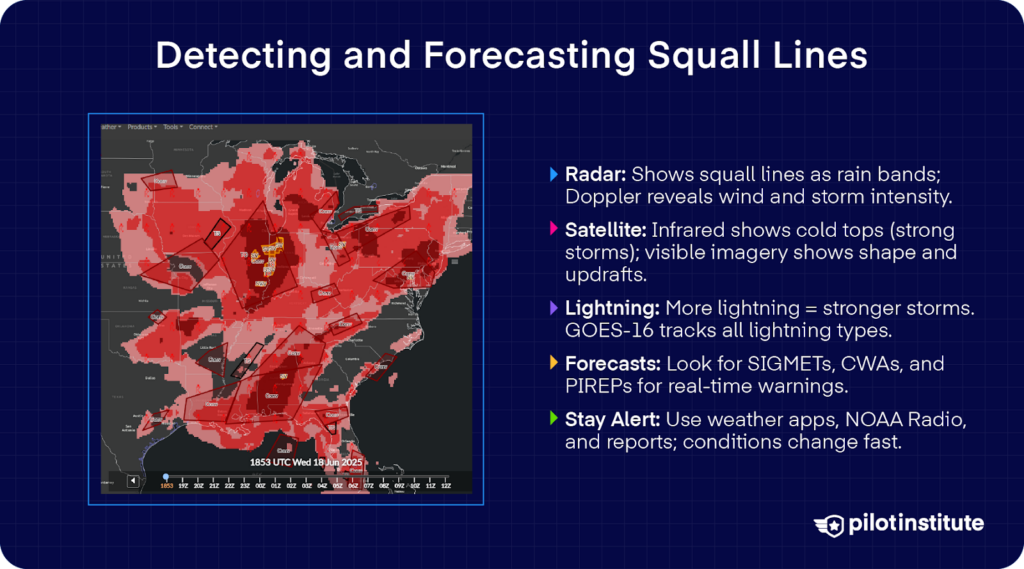

Detecting and Forecasting Squall Lines

- Radar Identification

- Satellite Imagery

- Lightning Detection Systems

- Weather Forecasts and Warnings

- Staying Informed

-

Conclusion

If you see a wall of dark, towering clouds stretching across the horizon and closing in rapidly, you’re looking at a squall line, and it could mean bad news.

Squall lines are powerful weather phenomena that can impact vast areas. They’re a threat to both aviation and everyday life.

So, to help you stay alert and aware, let’s talk about them and how you can be ready when one comes your way.

Key Takeaways

- A squall line is a band of thunderstorms that can stretch for hundreds of miles.

- Moisture, instability, lift, and wind shear are needed to form and sustain a squall line.

- Squall lines can bring strong turbulence, heavy rain, hail, lightning, and tornadoes.

- Weather radars and reports can help you plan ahead to avoid squall lines.

What Is a Squall Line?

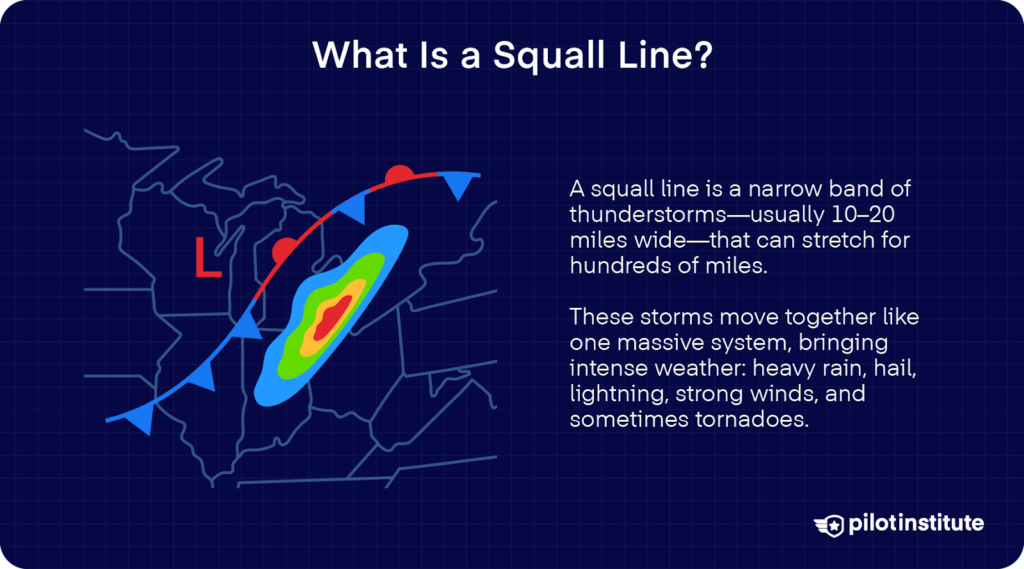

Sometimes thunderstorms will form in a band that can extend for hundreds of miles. This, in a nutshell, is a squall line. These lines can stretch for hundreds of miles but typically remain narrow, about 10 to 20 miles wide.

What’s it like to fly into a squall line? Well, they behave almost like a single, large storm system. Squall lines move as a cohesive unit and sweep across large regions.

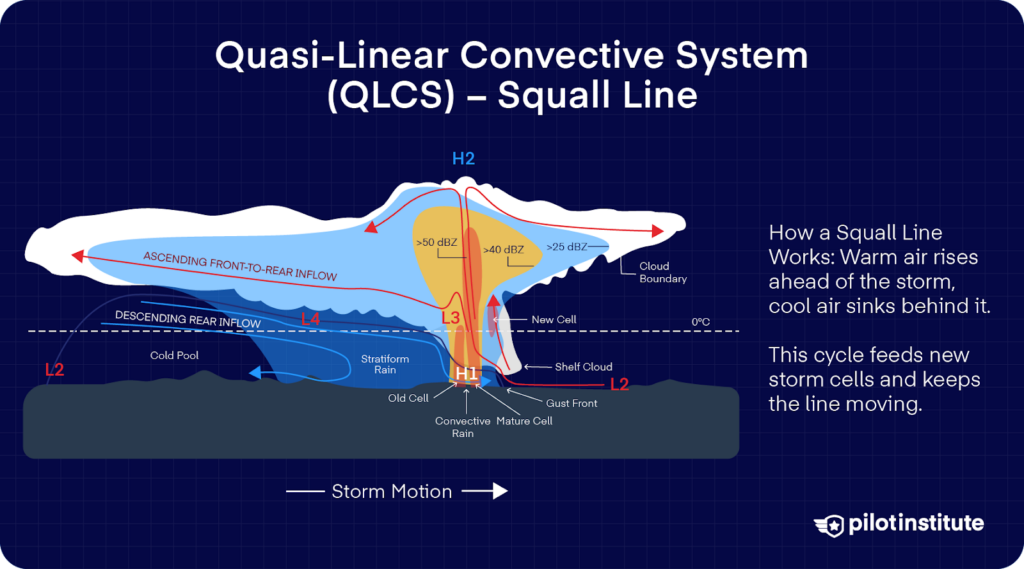

They deliver severe weather along their path. In meteorology, squall lines fall under the generic term Quasi-Linear Convective System (QLCS).

Because squall lines act as a unified phenomenon, they can cover a vast area with intense weather. And by “intense weather,” we mean the whole package: heavy precipitation, hail, frequent lightning, and strong straight-line winds. Sometimes, even tornadoes or waterspouts.

Formation of Squall Lines

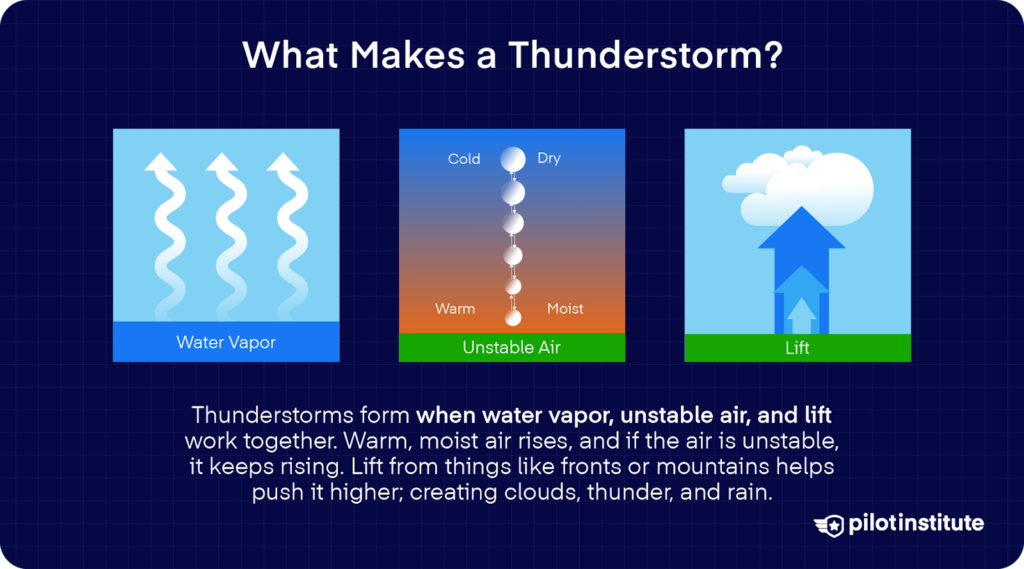

Squall lines often form where the right ingredients come together just the right way. Since they’re made of thunderstorms, they generally begin with the same process.

So, what do you need to make a thunderstorm?

Moisture

Moisture is typically measured by the surface dew point. Generally, you’ll need a dewpoint of 55°F or higher for a surface-based thunderstorm.

What does the dew point have to do with the formation of thunderstorms? Higher dew points mean more low-level moisture. Let’s see how this will fit into our puzzle.

Lifting Mechanism

Squall lines tend to develop along cold fronts, warm fronts, or dry lines. It’s these areas that act as natural lifting zones.

As dense, cooler air pushes under warmer air, it forces the warm air upward. It helps air parcels overcome the cap and reach levels where instability takes over.

Squall lines can form ahead of a cold front within the warm sector of a mid-latitude cyclone. In these areas, rising warm and moist air intensifies the line.

Atmospheric Instability

So far, we have two of the three ingredients for a thunderstorm. The final piece is atmospheric instability. Technically speaking, instability refers to the atmosphere’s ability to support rising air.

Air can become unstable due to many different factors. Let’s take our two puzzle pieces—moisture and lift—and see how they contribute to instability.

Once lifted, moist air can reach saturation and release latent heat. It becomes warmer and more buoyant than its surroundings.

In a conditionally unstable atmosphere, only saturated parcels continue upward, and the unsaturated parcels sink. This fuels deep convection and eventually, thunderstorms.

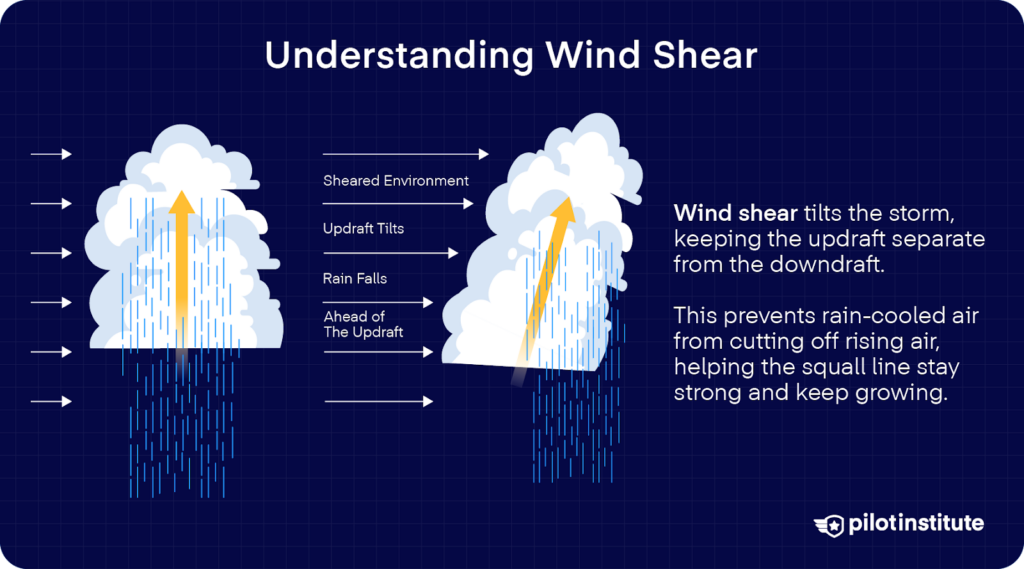

Wind Shear

But on top of all of that, there’s another piece of the puzzle that can help sustain the squall line.

Wind shear is the change in wind speed or direction with height. In a squall line, one of its main effects is tilting the storm. Wind shear is important in helping to forecast severe thunderstorms.

When the updraft is tilted away from the downdraft, the storm’s rising air becomes less cut off by its own rain-cooled air.

The uninterrupted updrafts then remain strong and last longer. With them, the squall line maintains its structure and keeps growing.

Squall Line Development Process

So, how do they all come together to make the perfect storm? Here’s how it happens, step-by-step:

1. Low-Level Convergence

As boundaries like cold fronts advance, strong convergence helps lift warm, moist air upward. Winds on the surface collide and force air aloft, and this triggers the process of storm development.

2. Thunderstorm Formation

As parcels of rising air reach their level of free convection, the first thunderstorms erupt along these convergence zones. This is where the elements of thunderstorm formation come into play, and a storm starts to brew.

3. Organization into a Line

Once the process starts, upper-level winds and vertical wind shear tilt and align storm updrafts. What used to be separated storms fall into a coherent, elongated line.

4. Maintenance and Propagation

A healthy balance between storm inflow of warm, moist air and outflow of cold, dense air from downdrafts keeps the squall line going. This, as you can remember, is also thanks to wind shear.

Gust Fronts

One of a squall line’s most powerful tools is the gust front. This is the leading edge of colder air descending from storms. This cold pool acts like a miniature cold front that lifts warm air ahead of it.

What could an additional lifting mechanism mean? New thunderstorms.

These gust fronts can trigger thunderstorm formation even far ahead of the main line, which sustains the squall line.

Characteristics of Squall Lines

So, what does a fully formed squall line look like? At the front of a squall line, a gust front forms when cool air from the storm’s downdrafts falls to the ground and spreads outward.

When this cool air meets the warm, moist air ahead of the storm, it forces that air to rise. As the warm air rises and condenses into clouds, it helps keep the storm alive and can even create new thunderstorms ahead of the main line.

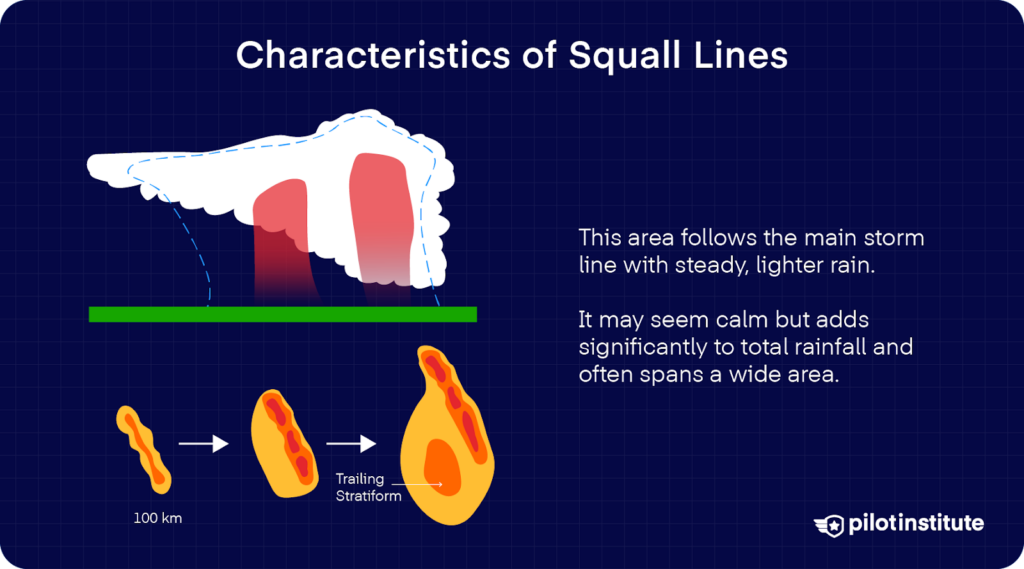

Trailing Stratiform Region

Behind the convective line lies the trailing stratiform region. This zone brings lighter, steadier rain that might not look very threatening, but still significantly contributes to the overall rainfall.

Studies and weather models show that this area consistently follows behind the stronger storm cells and can stretch across a vast region.

Visual Indicators

How can you spot a squall line with just the naked eye? Look out for shelf clouds. They are low, wedge-shaped arcus clouds attached to the leading edge of the storm.

These clouds mark the boundary where the gust front lifts warm air. They’re often a warning sign that there’s severe turbulence underneath.

You might also see roll clouds, which, unlike shelf clouds, are tube-shaped and detached from the parent storm.

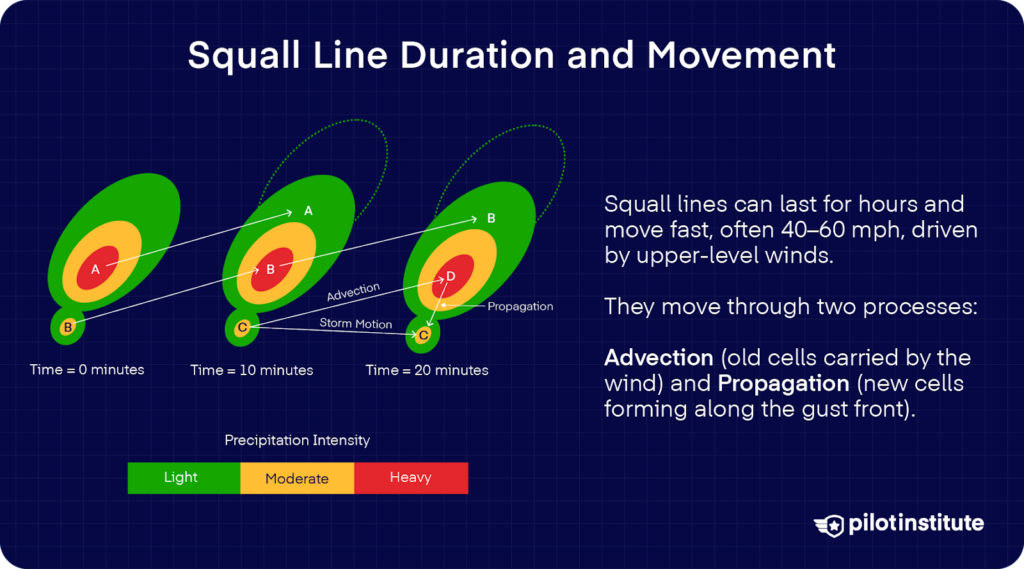

Squall Line Duration and Movement

Squall lines can persist for many hours or even over a day, as long as the right ingredients are available.

When it comes to movement, squall lines usually travel quickly, often at speeds of 40 to 60 miles per hour. Their speed is mainly powered by winds high in the atmosphere.

The movement of squall lines depends on two things. First is advection, which is the movement of storm cells by average winds throughout the atmosphere. Second is propagation, which stems from new cell formation along the gust front as old cells decay.

Individual cells that comprise the storm move northeast (advection), but dissipate and are replaced by new cells (propagation).

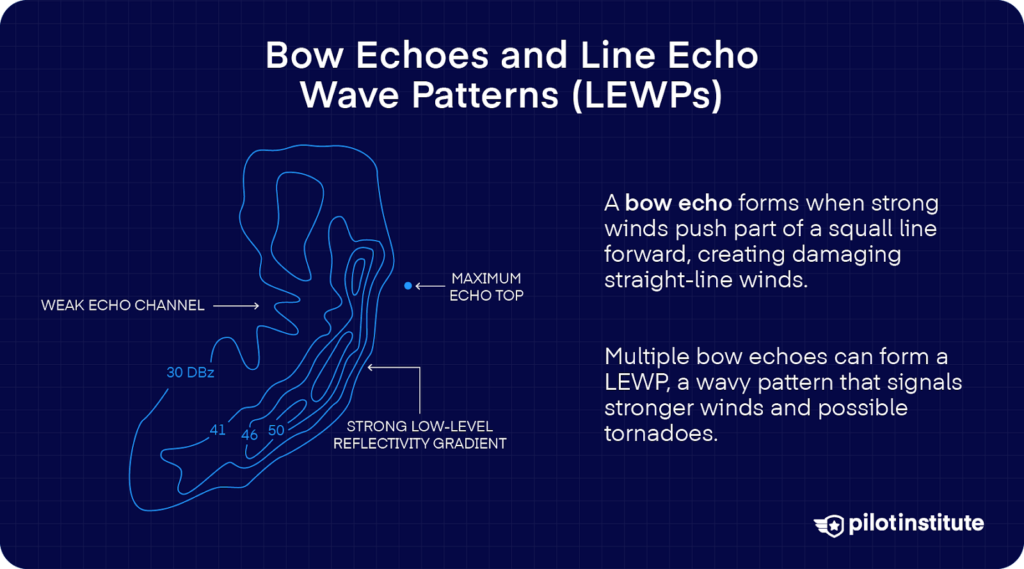

Bow Echoes and Line Echo Wave Patterns (LEWPs)

You might see a radar signature where part of a squall line curves outward. This forms a shape that looks like an archer’s bow, called a bow echo.

This happens when powerful winds—either from a rear inflow jet or a strong downburst—slam into the surface and push the middle of the storm line ahead of the rest.

These bow echoes are especially dangerous because they often produce strong, straight-line winds that can be just as damaging as a tornado.

Sometimes, several bow echoes form along the same squall line. When this happens, radar may show a Line Echo Wave Pattern (LEWP), which looks like a wavy structure.

How do these occur? A LEWP often starts where there are small, rotating low-pressure areas in the squall line. LEWPs are a warning sign for stronger straight-line winds and a higher chance of tornadoes. You’ll likely find them near the top or cyclone-facing side of each wave.

Weather Hazards Associated with Squall Lines

Downdrafts

Downbursts and microbursts are strong downdrafts that accelerate toward the ground and then spread out.

Inside bow echoes, you might encounter mid-level winds descending from the storm called rear inflow jets. But when these hazards reach the surface, they can strengthen the gust front and even worsen the already destructive winds.

In the most extreme scenario, a squall line could evolve into a derecho. They’re fast-moving systems that maintain at least 58 mph winds over a swath spanning over 400 miles. This includes several well-separated gusts exceeding 75 mph.

Heavy Rainfall and Flash Flooding

Expect a lot of rainfall when you’re in a squall line, especially if a training storm repeatedly moves over one place.

What can happen in this kind of weather? Flash flooding, which starts from rapidly rising water in streams. Urban drainage systems can be overwhelmed, leading to flooded houses, road closures, and heavy traffic.

Visibility is also heavily reduced. In a thunderstorm, it’s practically zero, which puts you at risk both in the air and on the ground.

Hail

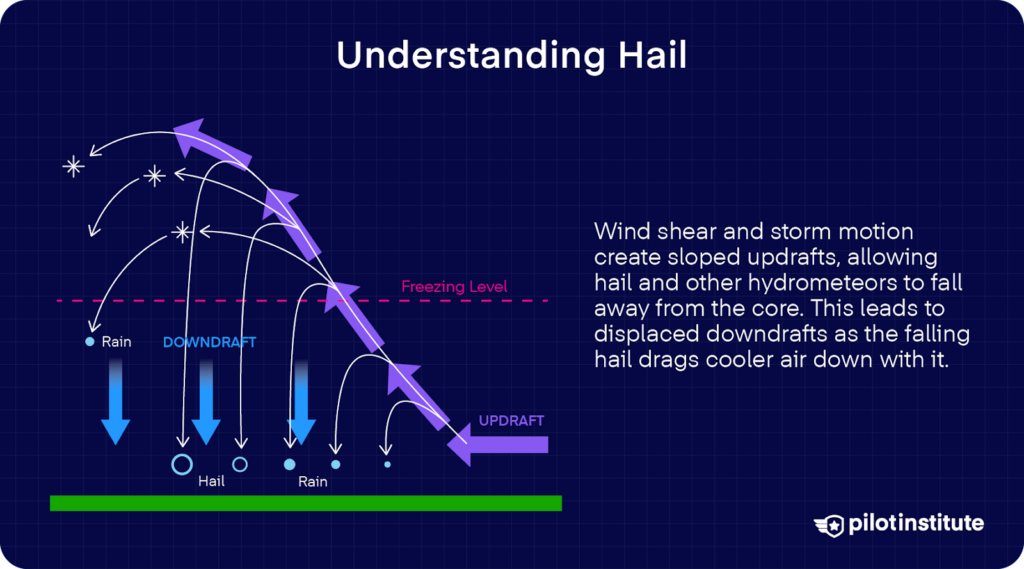

Strong updrafts can lift moisture above freezing altitude. This moisture turns into hailstones that fall back to the ground.

Remember that wind shear plays a hand in strengthening and reinforcing a squall line. But beyond this, Upper-level wind shears can blow hailstones horizontally away from the storm’s core.

As hail falls, it can damage vehicles and homes. Aircraft components aren’t safe either. Hail threatens both ground operations and in-flight safety.

Lightning

Squall lines are marked by frequent and intense lightning, and this is because of the strong charge separation within storm clouds. You’re at greater risk of a lightning strike when you fly around these systems, even if the air seems otherwise clear.

For your safety, you should seek shelter in buildings or vehicles with hard roofs. Stay away from open areas and tall objects. Corded phones or electrical appliances can attract lightning, so refrain from using them.

Tornadoes

Did you know that about 25 percent of all tornadoes in the United States come from squall lines? And even though they’re more common in supercells, they’re still a threat you shouldn’t ignore.

Small, intense areas of rotation called mesovortices can form inside bow echoes. These spinning areas often begin near the front part of the bow, where air is quickly pulled in and forced upward.

As this rising air stretches vertically, the spin becomes stronger, and that’s when a tornado is most likely to form.

These tornadoes may be hidden in heavy rain, so they can be tough to see. Always stay vigilant and pay careful attention to tornado warnings when there’s a squall line.

How to Avoid Squall Lines

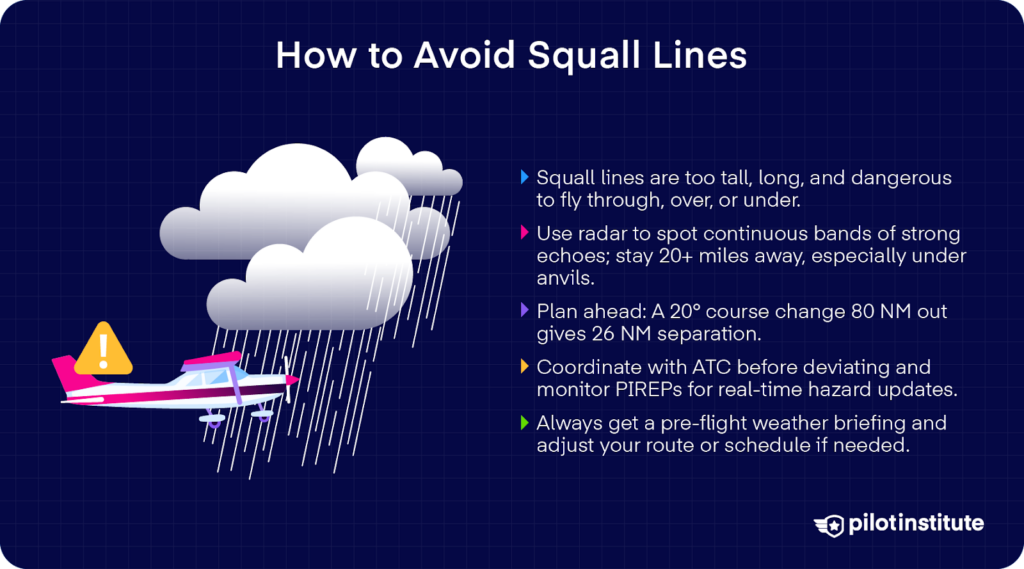

The FAA says that among all thunderstorm types, squall lines are the most effective barrier to air traffic. They’re usually too tall to fly over, too dangerous to fly through or under, and too long to fly around.

But can you even avoid a squall line? Yes, and here’s how.

Detection and Avoidance

To avoid squall lines, you should use onboard or ground-based weather radar. Look out for continuous lines of intense echoes that indicate moderate to heavy precipitation.

Remember that radar detects moisture, not turbulence. However, you can make the connection that areas of strong return generally also point to turbulence.

The FAA Advisory Circular AC 00‑24C says that you should maintain at least 20 miles of separation from storms with severe or intense echoes, especially under the anvil of a large cumulonimbus.

As you fly closer to a potential squall line, you should have a course of action planned in advance. But what steps can you take?

Let’s say you’re 80 NM away from the edge of the squall line. If you deviate just 20° off-course, after 80 NM, you’ll have a lateral displacement of 26 NM from the squall line.

Coordination with ATC

Another thing you shouldn’t forget is to maintain effective communication with Air Traffic Control (ATC).

Let them know about your intention to deviate before you make any changes. If you need it, you can ask for radar navigation assistance. Then, inform them you’re rejoining the planned route only after clearing the weather.

It also helps to monitor Pilot Reports (PIREPs) for turbulence or other hazards to support your situational awareness.

Flight Planning Considerations

The best way to ensure your survival is to be prepared for any threats ahead. A thorough pre-flight weather briefing is essential for your safety.

Look into the latest forecasts and advisories from sources like the Aviation Weather Center. Relevant briefings include:

- Severe Weather Warnings (WW).

- SIGMETs (WS).

- Convective SIGMETs (WST).

- AIRMETs (WA).

- Severe Weather Outlooks (AC).

- Center Weather Advisories (CWA).

- Area Forecasts (FA).

- Pilot Reports (UA/PIREP).

When you hear about a squall line forecast or development, you can either plan an alternate route or adjust your schedule. It might be wise to delay your departure or cancel the flight.

If you’re already en route, stay tuned for any weather updates or reports. You can find these from data-linked NEXRAD via FIS‑B, ATC radar advisories, HIWAS broadcasts, and direct PIREP requests.

Flight Service Stations (FSS) or En Route Flight Advisory Service (EFAS) help you stay updated on turbulence and weather reports. If any new developments point to danger, you should be ready to reroute or divert your flight.

Can You Fly Through a Squall Line?

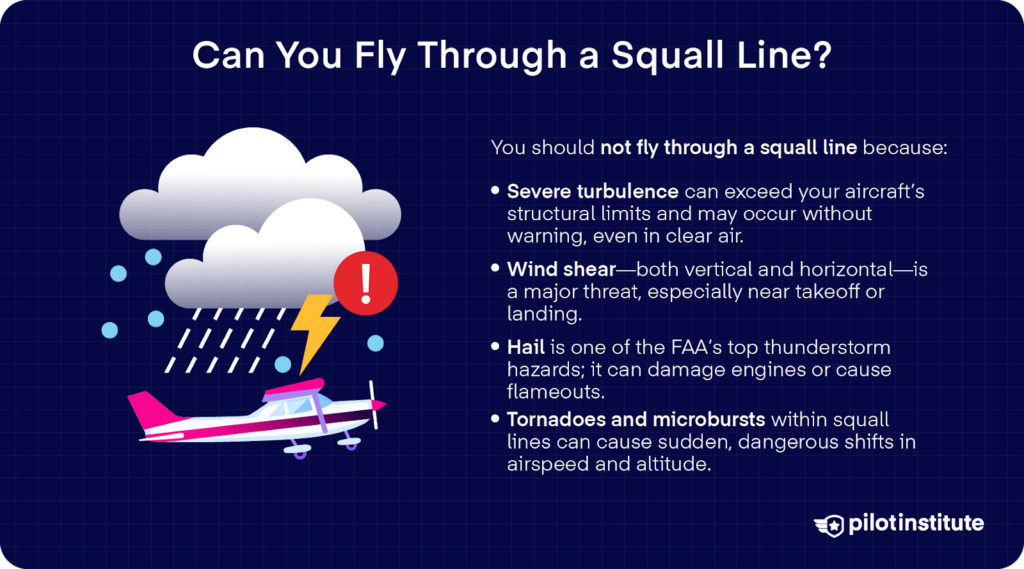

Out of curiosity or any hazardous attitude, you might be tempted to fly through a squall line. That’s why, at this point, we’d like to emphasize: flying through a squall line is exceptionally unsafe and must be avoided.

Turbulence and Wind Shear

Severe turbulence within these storms are often stronger than what your airplane’s structure can handle. It’s entirely possible for thunderstorm turbulence to destroy aircraft.

Turbulence and wind shear in thunderstorms are inherently violent, but what’s worse is that you won’t always see them coming. Watch out for extreme clear air turbulence, which can occur under the anvil of a storm.

Wind shear is a serious threat. Remember that it can occur both horizontally and vertically, and you’re most at risk during takeoff and landing.

Eastern Air Lines Flight 66 in 1975 tragically illustrates the danger of wind shear in squall lines. The aircraft was on its final approach to JFK when it flew into a deadly microburst. The aircraft struck approach lights, which caused it to catch fire and crash onto the runway.

Hail and Tornadoes

The FAA identifies two greatest hazards in a thunderstorm. The first is turbulence. The second is hail.

In fact, hail ingestion alone can cause flameouts or destroy critical components, as in the case of TACA Flight 110, where hail and rain led to dual engine flameouts.

Tornadoes and strong microbursts can also be lurking within a squall line. If you encounter them, you might experience abrupt fluctuations in airspeed and altitude that impair your control.

Detecting and Forecasting Squall Lines

Radar Identification

Weather radar is one of the best tools for spotting squall lines. On radar screens, squall lines appear as long, solid, or broken bands of heavy rain. These rain bands help show where the central part of the storm is located.

Doppler velocity data can also show how the wind moves inside the storm. This helps you see features like strong gusts of wind, rotating areas, or rear inflow jets.

Thanks to new radar technology, computers can now find and track these storm lines in real time, even before they’re fully formed.

Satellite Imagery

Satellites give another view of squall lines and their intensity. Infrared satellite images show cloud-top temperatures, and they work day and night.

What do cloud-top temperatures tell us? The colder the top, the higher and stronger the storm. If the tops get colder over time, it’s a sign that the storm is growing.

During the day, visible satellite images let forecasters see the actual cloud shapes and patterns. These images can show overshooting tops, which can also indicate strong updrafts and severe weather.

Lightning Detection Systems

Modern lightning detection systems track total lightning activity, both Cloud-to-Ground (CG) and Intra-Cloud (IC) flashes.

This goes for both ground-based networks and space-based sensors like the GOES-16 Geostationary Lightning Mapper (GLM).

A rise in lightning flash rates often means strengthening updrafts and intensifying convective systems. Lightning data now tend to go hand-in-hand with radar and satellite observations to issue early warnings.

Weather Forecasts and Warnings

Meteorologists and aviation authorities use different alerts to warn you about dangerous weather.

SIGMETs are urgent warnings sent out whenever there’s severe weather that could threaten aircraft. This includes squall lines, severe turbulence, large hail, strong winds, and even tornadoes. These alerts are sent as needed—there’s no fixed schedule.

Convective SIGMETs are a special type of SIGMET with a particular focus on thunderstorms. They’re sent out every hour or immediately if dangerous conditions arise suddenly.

Center Weather Advisories and Area Forecasts give frequent updates and often include maps and graphics to show where bad weather is forming or heading.

For real-time updates from other pilots flying in the area, you can listen out for PIREPs. These are especially useful because they describe weather events as they happen.

Staying Informed

Squall lines don’t just affect the aviation industry. The general public is also at risk when these events happen. The NOAA Weather Radio, weather apps, and local media broadcasts are all helpful tools in staying safe on the ground.

Since squall lines can form and evolve rapidly, everyone should stay tuned for continuous updates. Remember that situational awareness is a skill that can save you both inside and outside the cockpit.

Conclusion

Squall lines are powerful, fast-moving systems that can unleash chaos in minutes. They span hundreds of miles. When they come, they bring destructive winds and blinding rain.

That’s why it’s absolutely essential to understand them. The risks they pose both in the air and on the ground demand to be taken seriously.

We can always take smart, timely actions to stay safe. For us pilots, we must treat squall lines as no-go zones and plan ahead.

Knowledge is your first line of defense, and preparedness is your best ally. Listen to alerts, always have a plan, and keep on learning.