-

Key Takeaways

-

The Concern of Drones and Privacy

-

What the FAA Says About Drone Privacy

-

Local Laws on Drone Flights

-

Remote ID – The FAA’s System for Drone Transparency

- Compliance Options

- Enforcement and Penalties

- Impact on Drone Operations

-

How to Avoid Drone Privacy Problems

-

Frequently Asked Questions

-

Conclusion

If you’re wondering whether or not you can fly a drone over public property, the answer is yes.

However, privacy is one of the biggest and oldest issues with drone flight. Most people can relate to it. It’s easy to see where this concern can come from.

Drones started as tools for military surveillance operations. Modern drones are now better for surveillance. They have compact designs and advanced cameras.

If you’re going to fly your drone a lot, then you’re likely to encounter an argument regarding privacy at some point.

How can you resolve a privacy-related issue?

What can you do to make sure that you never run into privacy-related problems in the first place? Let’s explore these questions.

Key Takeaways

- Remote ID is now required for most drones in U.S. airspace.

- Privacy concerns with drones are common, especially with advanced cameras.

- Follow local, state, and federal laws to avoid privacy issues.

- Get consent and stay transparent to prevent privacy conflicts.

The Concern of Drones and Privacy

Since drones came on the scene, people have worried about spying, invading privacy, and recording without permission. After all, drones can fly just about anywhere and can be small enough to avoid instant detection.

Today’s drones are well-equipped for surveillance. They have cameras that capture images in low light. Some can also feature powerful zoom lenses and automatic subject tracking.

Are the fears of the public grounded on reality? Unfortunately, yes, they are. There have probably been hundreds of documented cases of drones violating the privacy of citizens.

In 2016, a man in Utah was able to chase down a drone that he caught flying outside of this bathroom. After finding the drone, the man saw it had many photos and videos. These showed people outside their apartments, likely taken without their consent.

A study from Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University found that private citizens are cautious about drone use. This includes drones used by hobbyists, professionals, and police officers.

The respondents liked using drones for police or rescue operations. However, they strongly opposed drones flying over their homes all the time.

Demographics help show which groups of people worry most about drone activity that might invade their privacy. Females are understandably more concerned about being videotaped without their consent. Conservatives on the political spectrum are less accepting of using drones widely.

What the FAA Says About Drone Privacy

The FAA is the top authority for the national airspace. They can restrict or regulate drone operations.

In recent years, the FAA has gradually expanded drone laws. Now, drone owners must register their devices. Also, pilots wanting to fly drones for business need certification.

Unfortunately, none of the FAA rules address the issue of privacy. As far as the FAA is concerned, drone pilots will encounter no problems as long as they fly within operational limits and stay out of “no-fly zones.” This has left a sizable gap in drone legislation which has gone unaddressed for what feels like a long time.

The FAA’s drone laws focus on keeping the national airspace safe. They also protect people and property on the ground.

Local Laws on Drone Flights

The FAA has worked on a system to identify drones and hold pilots accountable. We will explore this further later. In the meantime, state and city governments have created their own drone laws. These laws focus on privacy, safety, and security issues linked to drone use.

The biggest challenge of complying with these state or city-specific laws is that they can be very different across borders.

Some states try to classify unauthorized drone flights over private property as a misdemeanor, but these laws are often preempted by federal authority. Under 49 USC §40103, the FAA has exclusive control over U.S. airspace, so states can’t treat flight alone as trespassing or restrict altitude.

In contrast, other states may not have any regulations on drone operations at all. This means that drone pilots need to exercise due diligence whenever they fly their drones in a place where they have never done so before.

Sometimes, drone pilots question the validity of state or city drone laws. This is especially true when these laws clash with FAA regulations.

The FAA usually ends up with the ultimate authority in these cases, although we can imagine that the experience can’t be pleasant for a drone pilot. Legal cases are stressful and expensive, even when you come out on the winning side.

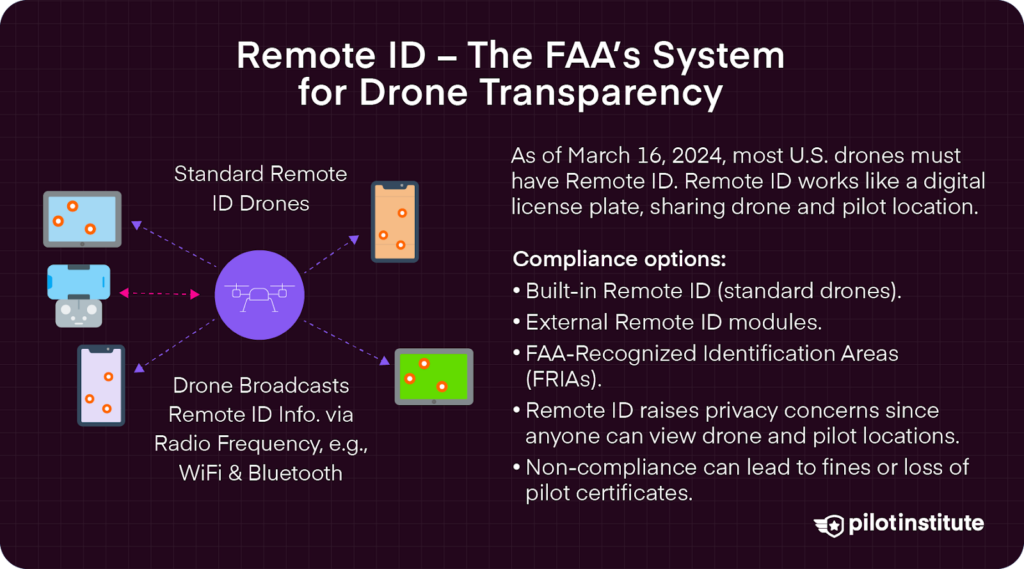

Remote ID – The FAA’s System for Drone Transparency

As of March 16, 2024, the FAA requires most drones operating in U.S. airspace to comply with Remote ID regulations.

Basically, remote ID acts like a “digital license plate.” It sends out your identification and location information while flying. This system boosts your awareness of airspace and helps law enforcement track drone activities.

Compliance Options

Drone operators have three methods to meet Remote ID requirements:

- Standard Remote ID Drones: Drones with built-in Remote ID capability that broadcast identification and location information directly from the drone.

- Remote ID Broadcast Modules: External modules that can be attached to drones lacking built-in Remote ID. These modules broadcast the necessary information but have some limitations compared to integrated systems.

- FAA-Recognized Identification Areas (FRIAs): Designated areas where drones without Remote ID can operate. Community-based organizations or educational institutions typically establish these and require FAA approval .

- Flying Drones Under .55lbs: For recreational purposes, does not require registration or remote ID.

Enforcement and Penalties

The FAA’s discretionary enforcement policy for Remote ID compliance ended on March 16, 2024. Operators who don’t follow Remote ID rules might face penalties. These can include fines or the loss of their drone pilot certificates.

Impact on Drone Operations

The implementation of Remote ID aims to integrate drones safely into national airspace. It adds new requirements for operators but also allows for advanced drone operations.

This includes flights beyond visual line of sight and flying over people. It creates a framework for safety and accountability.

How to Avoid Drone Privacy Problems

Currently, laws protecting people from rogue drones are inconsistent or weak. Some are easily challenged, and others don’t exist at all.

Just as prominent as cases of drones violating privacy are cases of people taking matters into their own hands. Shooting down drones is illegal, but your neighbor might not care. They may act if they think someone is recording them without permission.

While informing others that you’re flying is a good practice, pilots also need to know that random people can’t legally tell them to stop flying. If someone doesn’t like it, that’s unfortunate—but it’s not a valid reason to prevent someone from flying or to harass them while they do.

In 2017, the Commercial Drone Alliance opposed the proposed “Drone Aircraft Privacy and Transparency Act.” The community group created a set of voluntary best practices for drone pilots to help avoid privacy problems.

The guidelines were generally agreed upon by many industry and community members, as well as the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA).

The voluntary best practices should look familiar to any experienced photographer. Many of these guidelines focus on deliberate transparency. This means, while not required, getting consent from property owners for any aerial images and videos you use.

There may be cases when consent does not equate to compliance, especially if there are state or city laws in place to protect the privacy of citizens. If you’re not sure about the drone regulations of a place you’ve never operated in, then take the time to do a bit of research.

Check FAA approved sources related to drone regulations and laws. Locations such as Texas have their own regulations regarding drones and advise contacting the local municipality you’re filming in to see if they have their own additional regulations. It’s worth the time to cover all your bases before you start flying your drone.

The Commercial Drone Alliance guidelines stress the need to follow changing laws at the federal, state, and local levels.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Are drones an invasion of privacy?

Drones can invade privacy if they record images, videos, or data without consent. However, most drone pilots use drones responsibly, and privacy laws protect citizens.

- How do I stop drones from flying over my property?

You can contact local law enforcement if you believe a drone is invading your privacy. But avoid attempting to disable the drone yourself since damaging or interfering with the drone is illegal. They are considered aircraft under federal law.

- Is it legal to fly a drone over your neighbor’s property?

Flying a drone over private property is not illegal, and there is no minimum altitude. However, states and local municipalities with rules setting minimum altitudes are federally preempted.

- Are people allowed to fly drones around your house?

There is no reasonable expectation of privacy from the air when aircraft operations occur at “legal altitudes.” Drones don’t have a minimum legal altitude.

Conclusion

No matter how common drones become, concerns over privacy will probably always be there. People naturally feel wary of drones. This is especially true as they become common in our skies.

Perhaps new legislation and better drone flight etiquette will change the public perception of drone use.

For the most part, it is the burden of drone pilots to lay to rest any concerns with privacy. Drones can be used for good or bad. There are real cases of drones being used for voyeurism. This shows their potential for both noble and harmful purposes.

Only you know how honorably you’ll use your drone. It’s your job to show others they can trust you.