-

Key Takeaways

-

What is Class B Airspace?

- Horizontal Boundary

- Vertical Limit

-

Operating Requirements in Class B Airspace

- Operational Requirements

- Equipment Requirements

- Pilot Requirements

- Weather Requirements

-

Flying in Class B Airspace

- How to Enter Class B Airspace

- How to Operate Inside Class B Airspace

- How to Get Around Class B Airspace

-

Conclusion

Thinking about flying in Class B airspace but don’t know how to start?

It’s understandable. The fast jets and faster-talking controllers can be intimidating. Keeping track of all the rules and regulations might seem like too much.

If the complexity of this busy airspace feels overwhelming, don’t worry.

This article makes Class B airspace easy to understand. From entry and weather requirements to interacting with ATC, we have you covered.

Key Takeaways

- Class B airspace surrounds the nation’s busiest airports.

- Class B airspace features multiple tiers with shelves progressively spreading outwards up to 30 nm.

- Pilots must meet equipment and certification requirements and have ATC clearance to enter.

- VFR flyways, corridors, and transition routes help VFR traffic transit the crowded airspace.

What is Class B Airspace?

Class B (or Bravo) airspace surrounds the busiest airports in the country. The airspace funnels vast traffic volumes to and from major metro areas. You’ll always find a steady stream of airliners queued up for departure and arrival.

Class B airports are not only busy, they’re usually big as well. Airports such as ATL and JFK have multiple runways and cover around 5,000 acres of land.

Why are Class C and D airspace inadequate for such airports?

Class C and D airspace are less tightly controlled and cover smaller areas. These simpler classes cannot handle major international airports’ constant high-speed jet traffic.

Managing so many aircraft is challenging. Keeping jet traffic safe alongside slower general aviation aircraft is harder still. This is why large airports require complex multi-layered Class B airspace.

Horizontal Boundary

Class B airspace typically centers around one major airport, the primary airport. Some locations, like the New York City metropolitan area, have several primary airports.

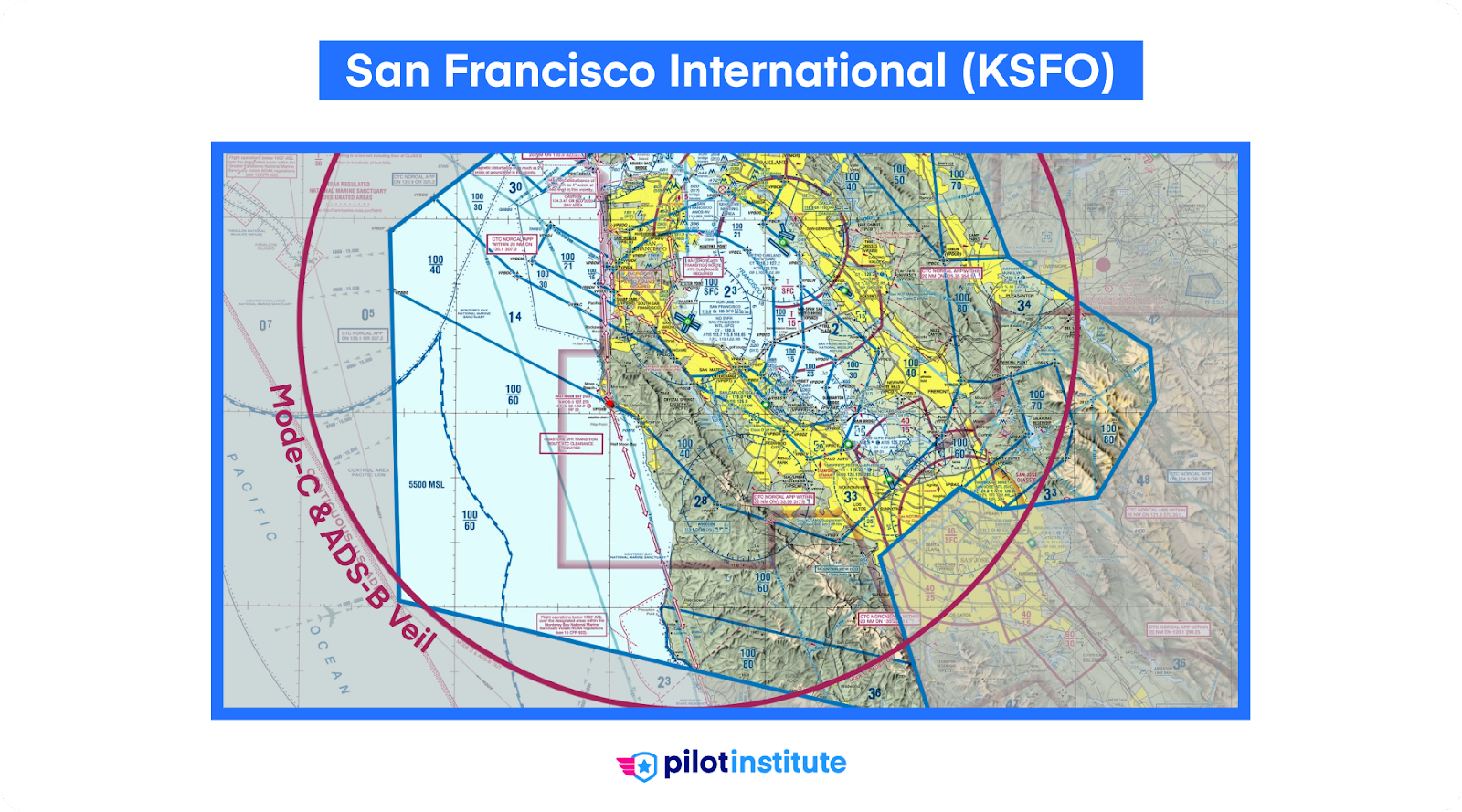

Class B airspace doesn’t have a standard shape. Simpler Class B designs resemble concentric circles. Others, like San Francisco’s airspace, look more like a random patchwork of segments. However, the airspace is anything but random. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has tailored each airspace to ensure traffic flows in and out of the airport safely.

The FAA also designs Class B airspace to have minimal impact on nearby satellite airports. They try to make the underlying airspace easily navigable by visual flight rules (VFR) aircraft. For example, the FAA modified SFO’s Class B to provide more room for VFR aircraft under terminal arrivals.

Chart Depiction

Terminal Area Charts (TACs) are specifically designed to show Class B airspace in detail. Class B airspace is also charted on VFR Sectionals and instrument flight rules (IFR) Enroute Low Altitude charts.

All charts depict Class B airspace boundaries with thick, solid blue lines.

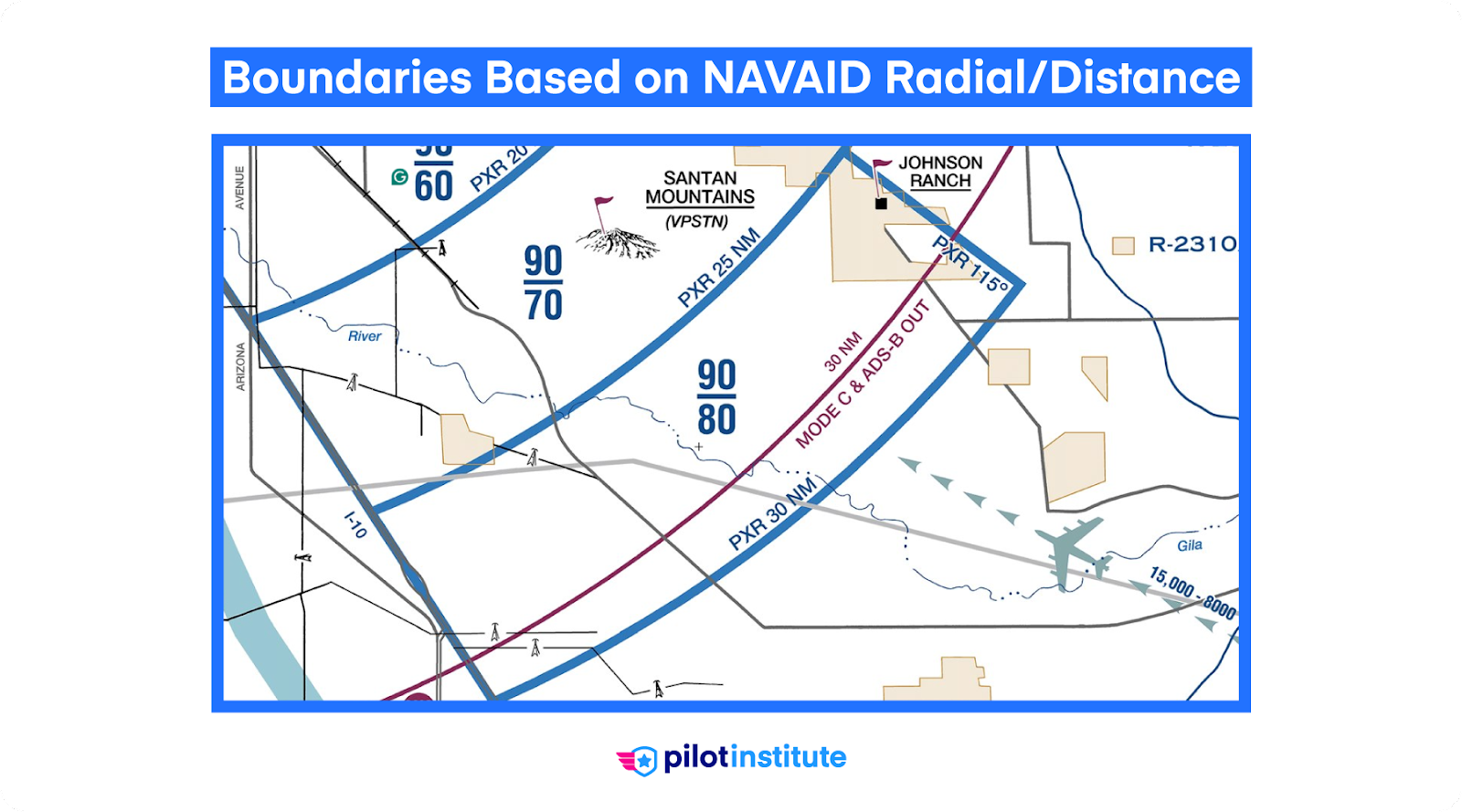

Mode C Veil

The Mode C Veil is a 30-nautical mile boundary around a Class B airport. It extends from the surface up to 10,000 feet MSL. All aircraft inside the veil must have an operating Mode C transponder and ADS-B Out. This allows controllers to monitor nearby traffic, even if they’re not talking to them.

Mode C Veils are present around most Class B airports. A complete list is available in the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Section 1, Appendix D to Part 91.

Parts of Class B airspace sometimes extend beyond the Mode C circle, like at SFO. This can also happen when the navigational aid defining the airspace is offset from the airport.

Phoenix Sky Harbor is a great example of this. The Mode C veil uses the airport as its center, while the Bravo airspace is centered around the PXR VORTAC.

Vertical Limit

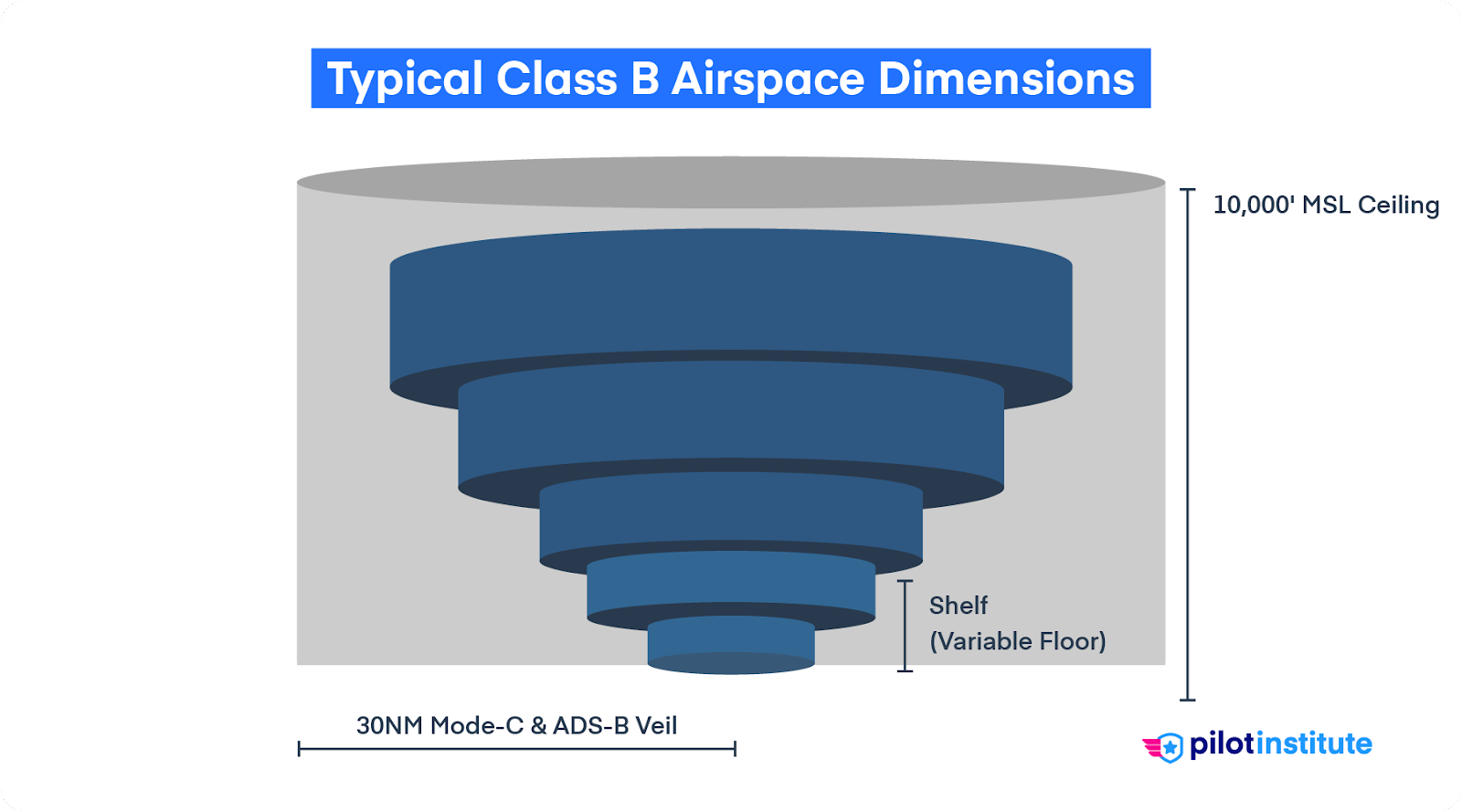

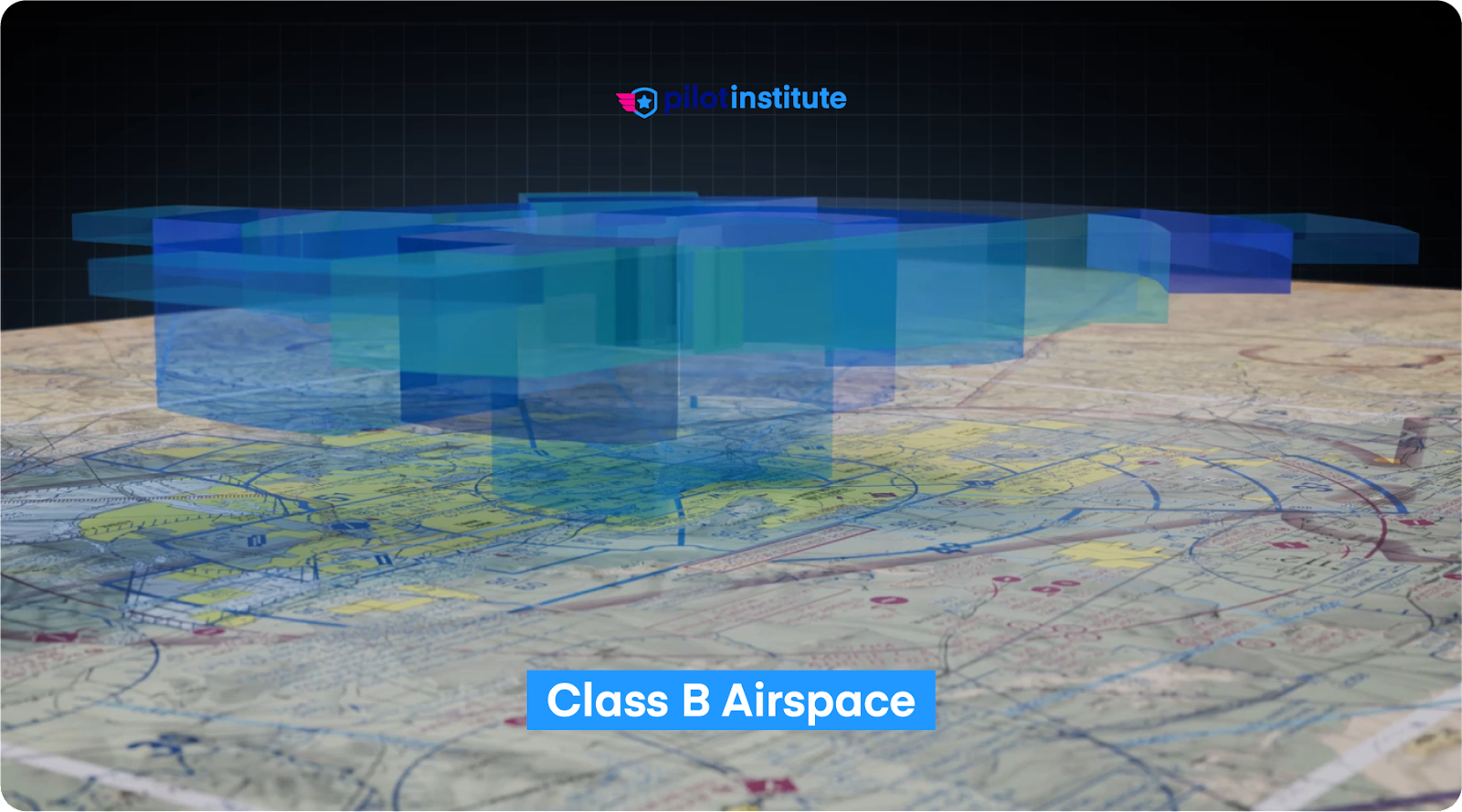

The airspace surrounding Class B’s primary airport(s) starts at the surface. This central core extends up to around 10,000 feet MSL, the airspace’s ceiling. Two or more additional layers – or shelves – cover arrival and departure routes. The shelves extend outwards from the core.

As we move outwards from the airport, each shelf’s base altitude – or floor – increases. This allows air traffic to safely operate independently underneath the Class B airspace. However, the ceiling for each shelf is the same as the core. If depicted in 3D, the resulting airspace looks like an upside-down wedding cake.

Although Class B airspace has a typical ceiling of 10,000 feet MSL, exceptions exist. Due to its high elevation, Denver’s Class B airspace extends up to 12,000 feet MSL to give airliners room to descend. New York’s Class B airspace has a 7,000-foot ceiling, allowing more room for overflying aircraft.

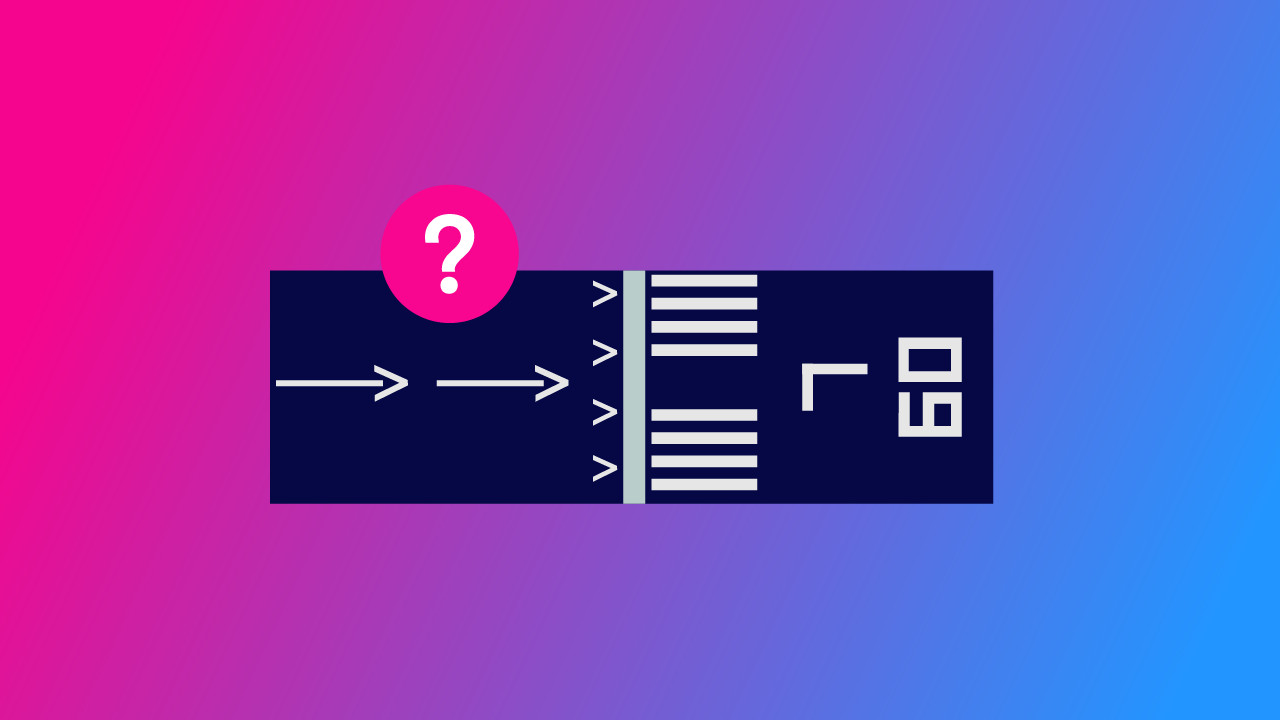

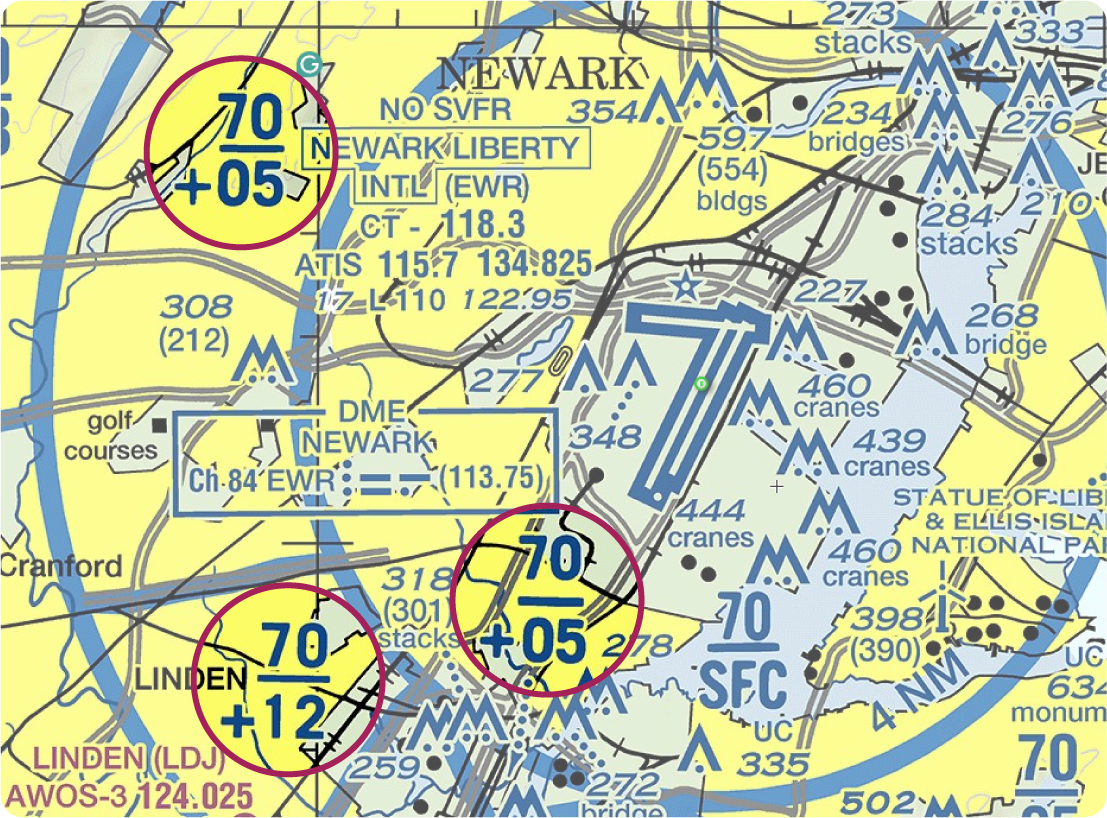

Vertical limits for each section of the airspace are depicted with dark blue labels. These labels show two numbers separated by a line.

The number on top represents the ceiling, while the lower number is the floor. These numbers designate the altitude in hundreds of feet MSL. For example, 30 means 3,000 feet.

Surface areas have ‘SFC’ written instead of the lower number. Occasionally, you’ll see a + sign preceding the lower number. This plus sign means the airspace floor starts above the altitude shown on the chart.

Operating Requirements in Class B Airspace

Operational Requirements

VFR traffic needs explicit clearance to enter Bravo airspace. Two-way radio contact with the approach controller is not enough.

If you’re flying under IFR, you don’t need an explicit Bravo clearance. Your IFR clearance authorizes you to fly your planned route.

Regardless of flight rules, you must meet the equipment requirements before entering.

Equipment Requirements

- A two-way radio.

- A Mode-C transponder (automatic altitude reporting capability) inside the Mode C Veil.

- ADS-B Out inside the Mode C Veil.

- If flying under IFR, you’ll need a VOR or TACAN receiver, or an RNAV system (GPS).

Pilot Requirements

You’re allowed to enter Class B airspace only if:

- The PIC (Pilot in Command) holds at least a private pilot certificate.

- The PIC holds a recreational pilot certificate and meets the requirements of 14 CFR § 61.101.

- The PIC holds a sport pilot certificate with 14 CFR § 61.325 endorsements.

- You’re a student training for a private pilot certificate with an endorsement for 14 CFR § 61.95.

- You’re a student training for a recreational or sport pilot certificate with endorsements for 14 CFR § 61.94.

Operating at some Class B airports requires a minimum of a private pilot certificate. These primary airports have some of the country’s busiest and most complex airspace. They cannot afford to give student, sport, and recreational pilots the necessary attention.

You’ll need at least a private pilot license to take off or land solo at the following airports.

| FAA LID / ICAO Code | Airport Name |

| ADW / KADW | Andrews Air Force Base, MD. |

| ATL / KATL | Atlanta Hartsfield Airport, GA. |

| BOS / KBOS | Boston Logan Airport, MA. |

| ORD / KORD | Chicago O’Hare Intl. Airport, IL. |

| DFW / KDFW | Dallas/Fort Worth Intl. Airport, TX. |

| LAX / KLAX | Los Angeles Intl. Airport, CA. |

| MIA / KMIA | Miami Intl. Airport, FL. |

| EWR / KEWR | Newark Intl. Airport, NJ. |

| JFK / KJFK | New York Kennedy Airport, NY. |

| LGA / KLGA | New York La Guardia Airport, NY. |

| DCA / KDCA | Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport, DC. |

| SFO / KSFO | San Francisco Intl. Airport, CA. |

Weather Requirements

We find the VFR weather requirements in 14 CFR § 91.155.

VFR operations in Class B require:

- Flight Visibility of at least three statute miles.

- Remaining clear of clouds with no minimum distance requirement.

These limits aren’t as strict as those in other controlled airspace classes. Why?

Class B airspace can afford looser weather requirements because ATC tracks traffic closely. The controller handles the separation between all aircraft. So, you don’t have to fear aircraft popping out of clouds without warning.

However, additional visibility requirements exist for VFR traffic at a primary airport.

If the airport reports ground visibility of less than three statute miles, you can’t take off, land, or enter the traffic pattern. At airports that don’t have ground visibility equipment, use flight visibility instead.

Class B primary airports will also restrict VFR operations when the ceiling is less than 1,000 feet.

SVFR Operations

It’s possible to work around VFR weather limits at some Class B airports. How? By requesting a Special VFR (SVFR) clearance before entering the airspace. SVFR has its own requirements, which you can read here.

According to 14 CFR § 91.157, SVFR is only allowed in the surface area and the airspace directly above it, up to 10,000 feet. That means it’s only allowed in and above the core but not in the shelves of the Bravo airspace.

Note that many Class B airspaces prohibit SVFR operations due to high volumes of IFR traffic. Charts indicate airports that don’t allow SVFR.

Flying in Class B Airspace

How to Enter Class B Airspace

VFR aircraft must remain outside the Class B until the controller clears them to enter.

To request Bravo clearance, call the approach controller when you’re about 30-40 miles out. Provide your callsign, location, altitude, and destination. The controller will identify you on radar, assign you a squawk code, and clear you into the airspace.

If you’re departing from a satellite airport under Class B, call approach right after takeoff. If the satellite airport has a control tower, they can help coordinate. However, you must receive clearance from approach control before entering Class B airspace.

Bravo airspace is almost always busy. But it can be particularly hectic at certain times of the day. This is called a ‘push’. ATC is very likely to refuse VFR Bravo clearances during a push. They’ll ask you to remain outside Bravo airspace and advise you when to expect further clearance.

How to Operate Inside Class B Airspace

Once inside the Bravo, you must pay strict attention. You’re responsible for maintaining situational awareness, ATC communication, and following airspace rules. The airspace is busy, and there is no room for error.

Airspeed Restrictions

Almost all Class B airspace exists below 10,000 feet. This effectively limits traffic in Class B to 250 knots due to 14 CFR § 91.117(a). Traffic flying under a shelf or through a VFR corridor needs to stay below 200 knots.

Traffic Separation

ATC will separate VFR traffic from all other VFR and IFR aircraft. They’ll provide at least 500 feet of vertical separation. Lateral separation will be at least 1 ½ miles for jets and large aircraft or target resolution for small aircraft. ATC may allow visual separation at its discretion.

Landing at Class B Airports

If you plan to land at a Class B airport, here’s what you need to know.

Call ahead to prearrange your arrival. ATC will advise you of the off-peak times when entry into the airspace is less likely to be denied.

Don’t attempt a landing at a Class B airport without extensive preparation. Listen to ATC transmissions to familiarize yourself with the airspace. Learn the typical approaches and altitudes. Determine the common taxi routes.

Controllers juggle a large number of aircraft at any given time. Clearances can be long and complex, and you must keep up with rapid-fire ATC chatter. You’ll need to stay sharp even after landing. Taxi clearances can be very complicated.

Has it been a while since you flew out of a busy commercial airport? Consider improving your skills at a busy Class D or C airport first.

How to Get Around Class B Airspace

Compared to other airport airspaces like Classes C and D, Class B airspace is huge! The widest shelves can extend as far as 30 miles from the primary airport.

That’s a considerable detour for small general aviation aircraft. Terrain or weather around the airspace can add time and fuel consumption. Here’s how to bypass the Bravo.

Flying Under or Around Class B

Despite its imposing size, you can transit the Class B airspace without major detours. Just fly under a shelf!

You don’t need a clearance since you’re not entering Bravo airspace. However, you will need an operating Mode C transponder and ADS-B Out.

You’ll also have to limit your speed to 200 knots, obeying 14 CFR § 91.117(c). Traffic avoidance is your responsibility when you’re flying VFR. Expect considerable traffic near Class B airspace. The reduced speeds help you see and avoid other aircraft.

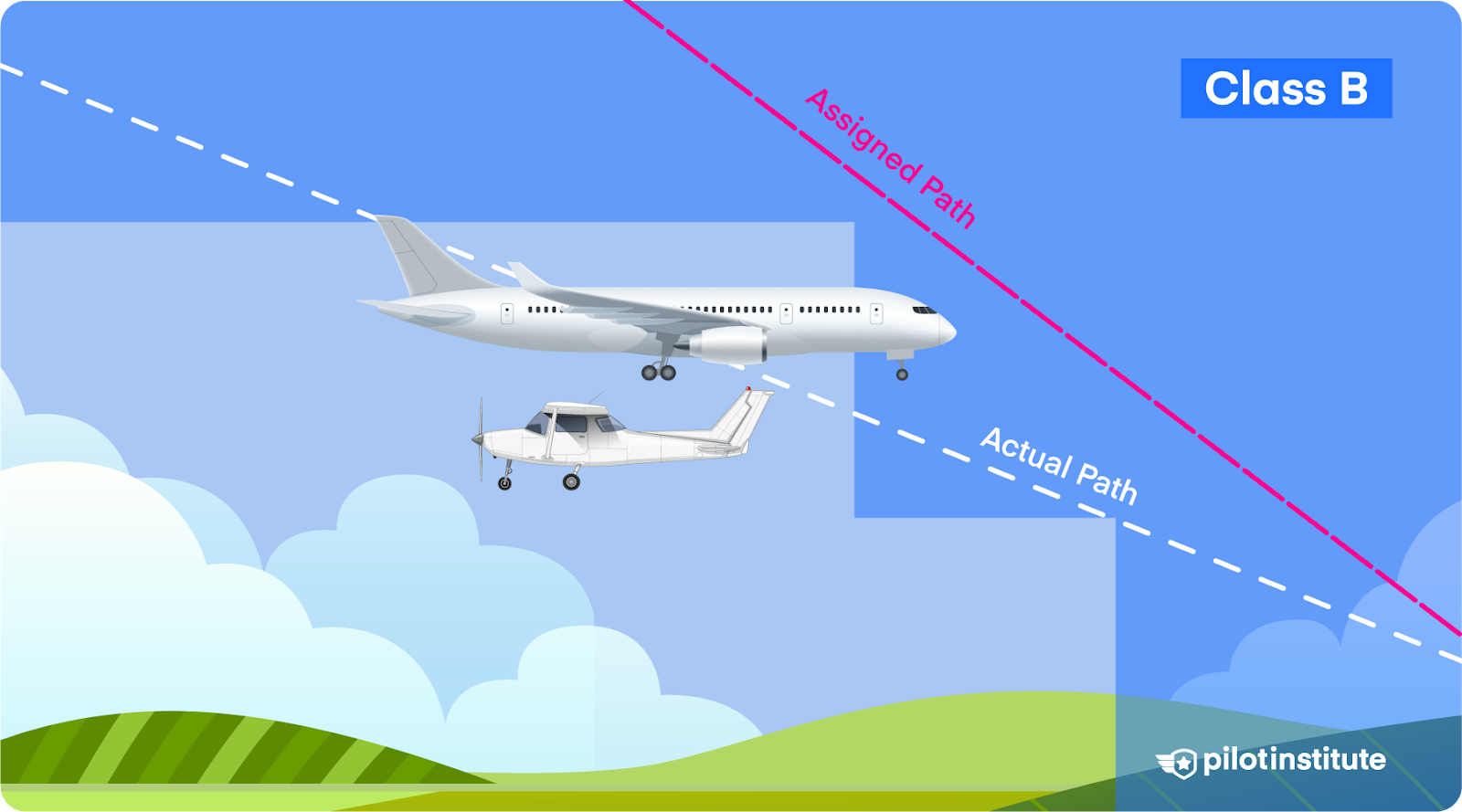

Stay clear of the Class B boundaries if you’re flying under a shelf with a floor less than 3,000 feet AGL. This prevents unintended airspace incursions and provides a safety buffer from traffic.

Class B excursions are increasingly common. They often happen when aircraft descend early on a visual approach. This puts them at risk of descending through the airspace floor.

Consider keeping a 500-foot vertical and two-to-three-mile lateral margin from the airspace boundary. You don’t want an incorrect altimeter setting to cause an airspace incursion.

To avoid conflicts, follow the VFR cruising altitudes laid out in 14 CFR § 91.159. Consider getting flight following to improve your situational awareness.

Following Published VFR Routes

Some Class B airspaces help transiting VFR traffic by publishing routes for guidance.

VFR Flyways

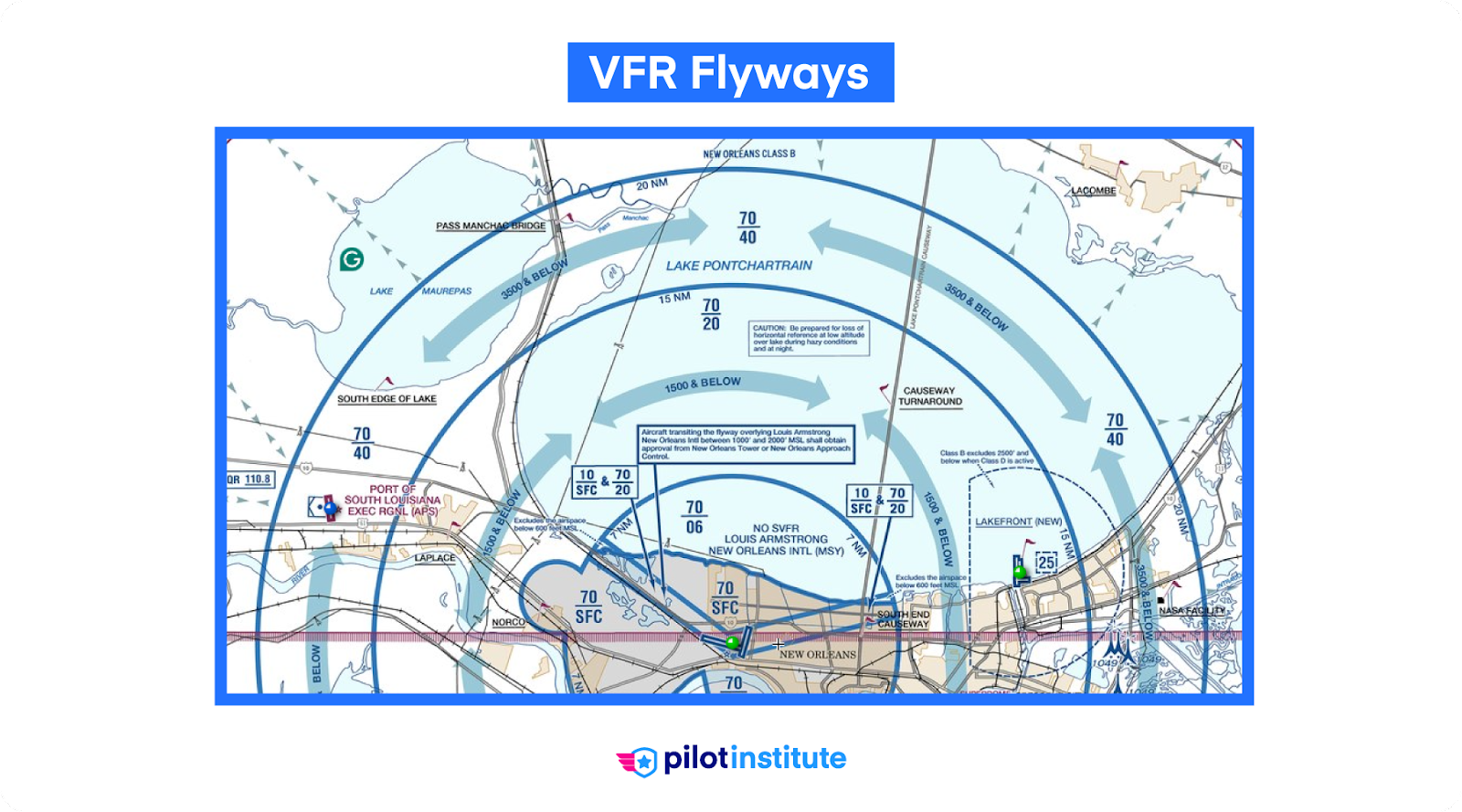

VFR Flyways are routes aircraft can use when skirting the Bravo airspace. They aren’t mandatory, but ATC recommends using them. They are depicted on VFR flyway planning charts on the backside of the airport’s TAC.

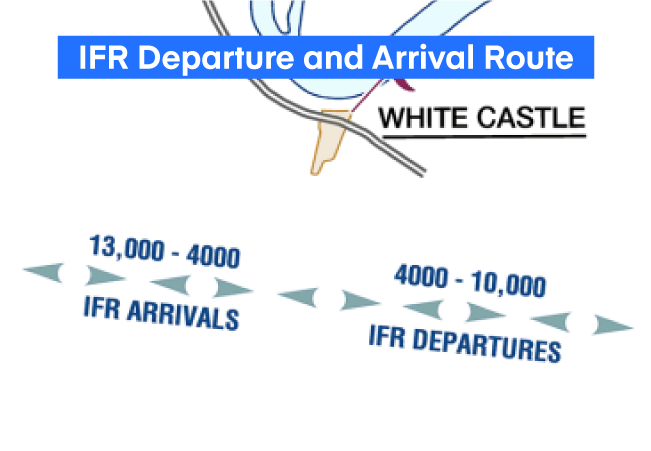

The flyway routes are shown with blue arrows, along with their recommended altitudes. They include notable landmarks and obstructions to help with visual navigation. Common IFR routes are also shown to let VFR pilots know where to expect fast-moving traffic.

VFR flyways don’t require a clearance. However, you still must contact any Class C/D controllers if you cross their airspace en route.

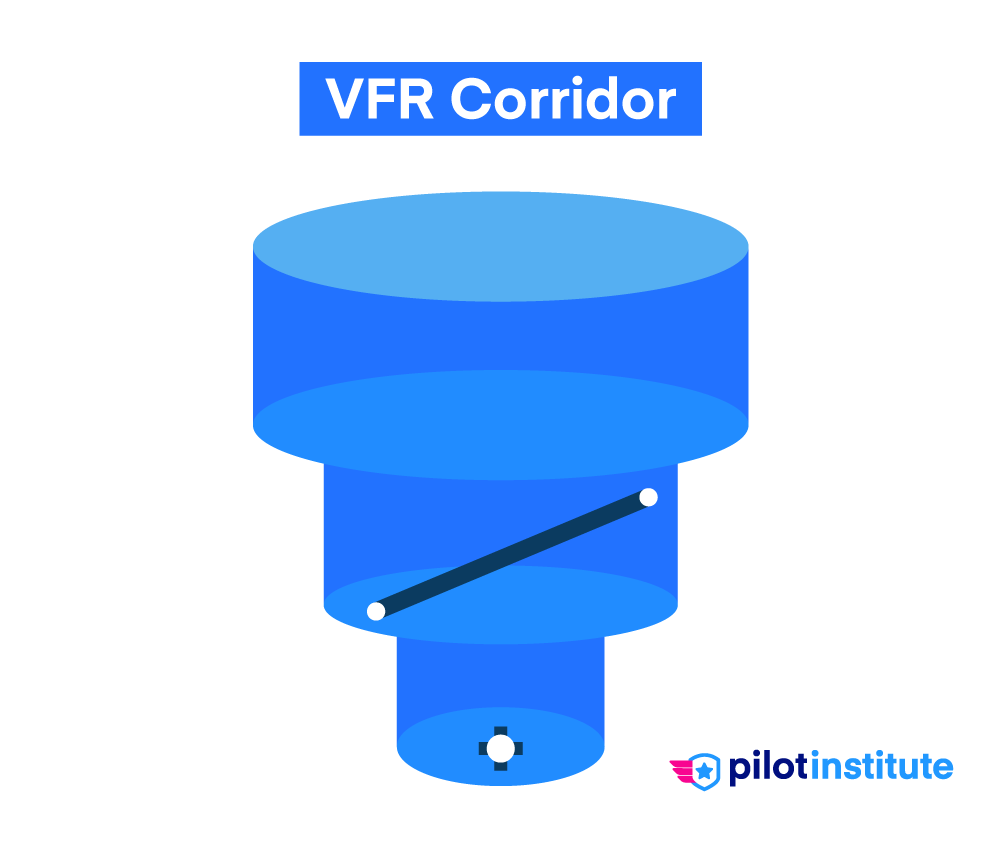

VFR Corridors

Some Class B airspace features a route right through the middle for VFR traffic. You can fly through these “holes” within the airspace without a Bravo clearance.

VFR corridors are often heavily congested. Their limited dimensions require great care when navigating them. They’re typically placed above the primary airport’s surface area.

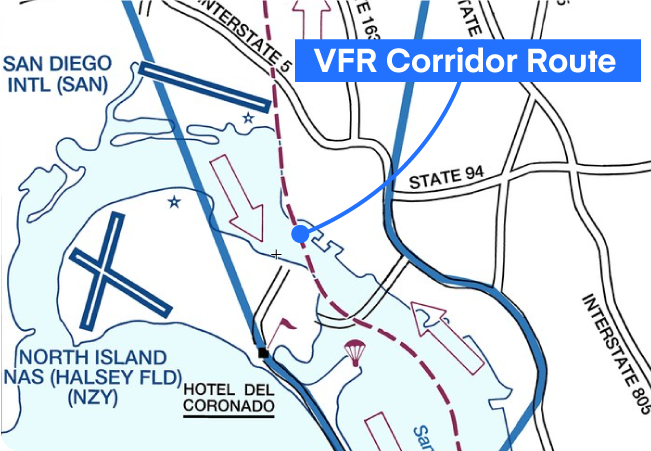

San Diego’s TAC shows the VFR corridor depicted with a red dashed line. Red arrows show the direction of travel, while the altitude limits are also labeled. Aircraft use a specific frequency to give each other position reports.

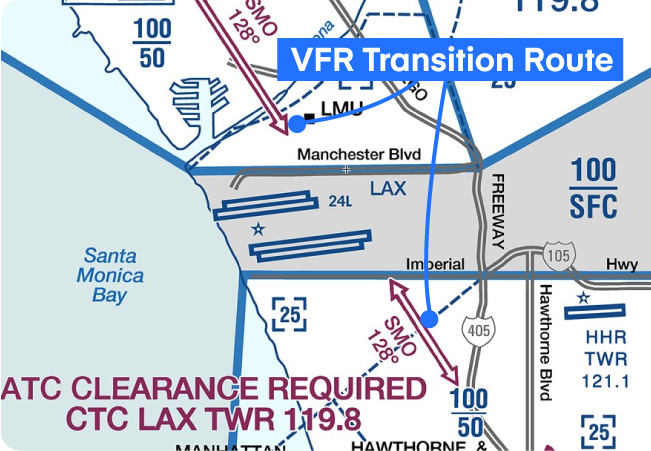

VFR Transition Routes

Some Bravo airspaces have traffic volumes that are too much for a VFR corridor to handle. The FAA developed VFR transition routes for these locations.

Unlike other methods, VFR transition routes require Bravo clearance before entry. They’re represented on TACs with red double-sided arrows and often have their own names.

The image shows the Mini route over Los Angeles. The course is predefined, but ATC will assign altitudes.

Conclusion

Learning to navigate Class B airspace is difficult. It’s complex, busy, and fast, which many general aviation pilots find intimidating.

However, with preparation and knowledge, you’ll be ready to take on the challenge.

If you’re new to flying out of towered airports, Class B is not the best place to start. Thankfully, several smaller airspace options exist.Want to learn more about other airspace classes? Find out how other classes work in this comprehensive guide to airspace.