-

Airspace Classes

- What Is an Airspace Class?

- Controlled and Uncontrolled Airspace

- Class A Airspace

- Class B Airspace

- Class C Airspace

- Class D Airspace

- Class E Airspace

- Class G Airspace

-

Special Use Airspace

- Restricted Areas

- Prohibited Areas

- Warning Areas

- Military Operation Areas (MOAs)

- Alert Areas

- National Security Areas (NSAs)

-

Other Airspace Areas

- Temporary Flight Restrictions (TFRs)

- Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ)

- Military Training Routes (MTRs)

- VFR Flyway

- VFR Transition Routes

- Terminal Radar Service Areas (TRSA)

- Special Flight Rules Areas (SFRAs)

- Special Air Traffic Rules Areas (SATRs)

-

Conclusion

Ever feel confused about the complex definitions of airspace?

You’re not alone.

Without a solid understanding of the different types of airspace, you risk an awkward conversation with ATC at best and a trip to court at worst.

Let’s make sure that doesn’t happen to you.

In this article, we’ll cover everything you need to know about airspace in the US.

Airspace Classes

What Is an Airspace Class?

A class is a type of airspace. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) defines classes using letters like A or B.

The needs of the airspace determine which class to use.

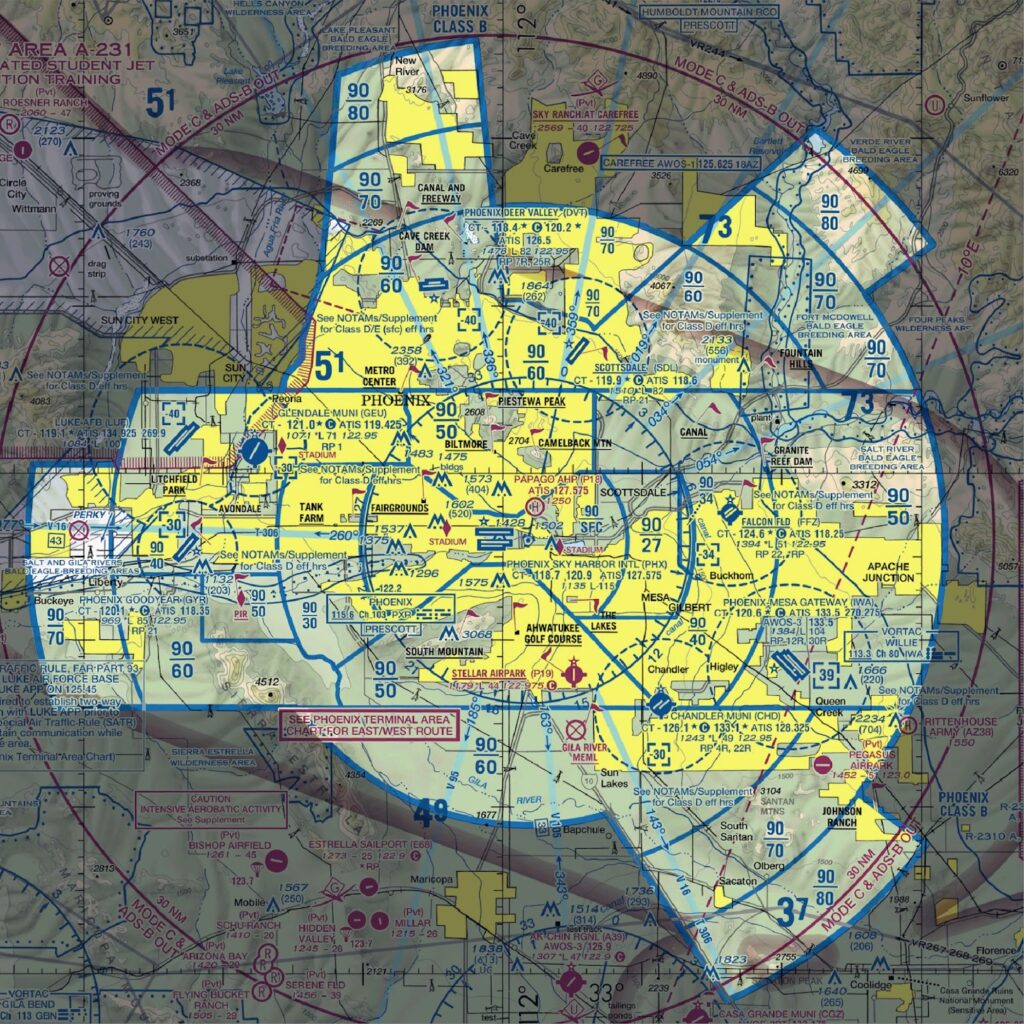

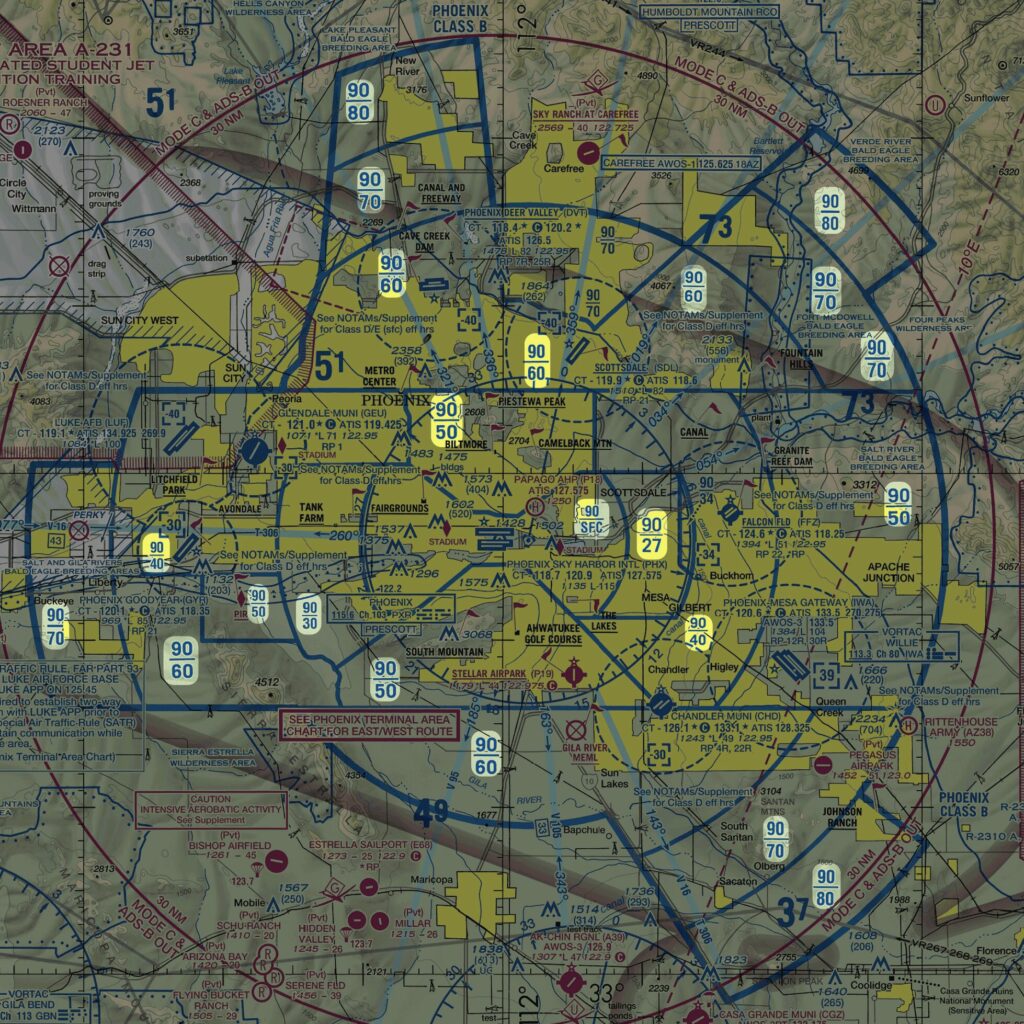

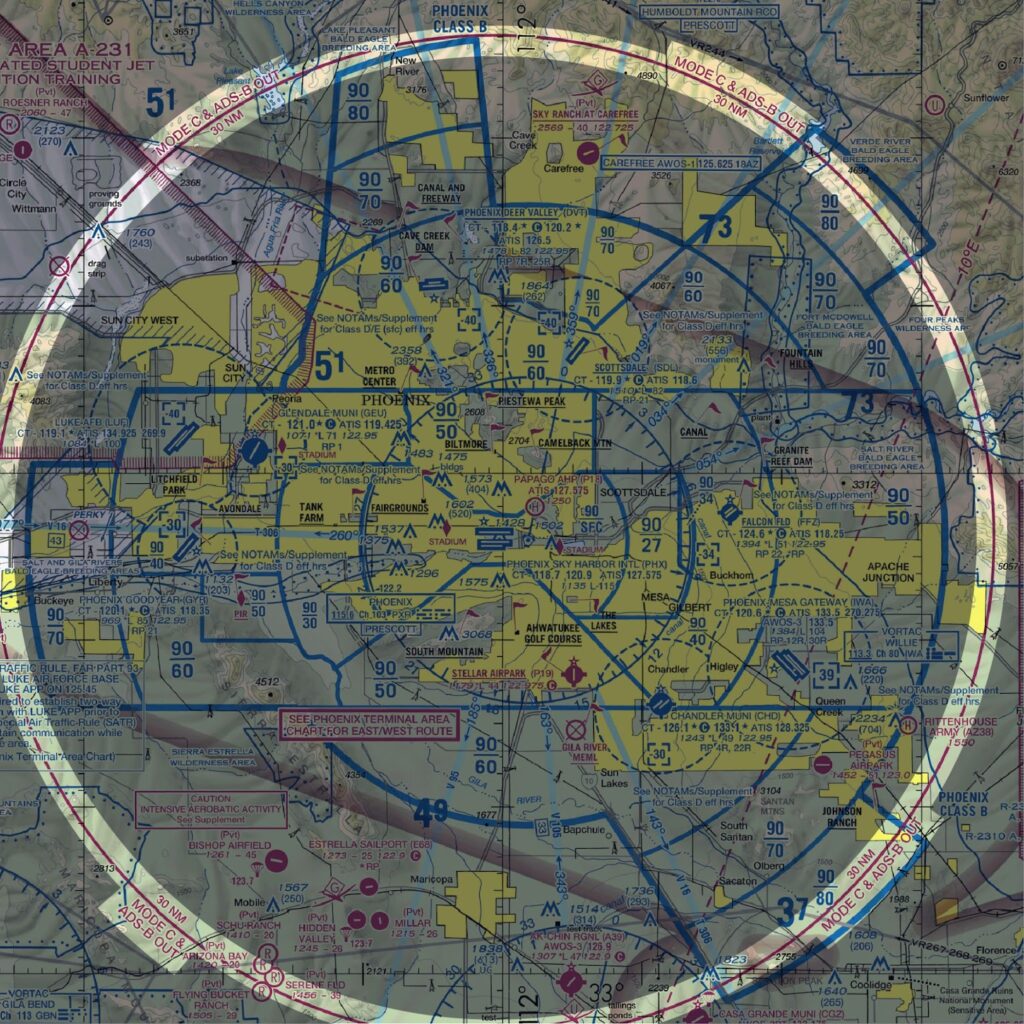

For example, Phoenix’s bustling Sky Harbor International Airport has a high volume of airliner traffic. The custom-made Class B airspace keeps the busy operations moving safely.

Nearby Casa Grande Municipal Airport is much smaller and has no airliner operations. Class G airspace works well for this airport’s more basic needs.

But what do these classes mean?

Let’s find out.

Controlled and Uncontrolled Airspace

A class of airspace is either controlled or uncontrolled.

Controlled airspace is where air traffic control (ATC) has the authority to control traffic. In uncontrolled airspace, they don’t. Any guidance ATC gives pilots in uncontrolled airspace is advisory only.

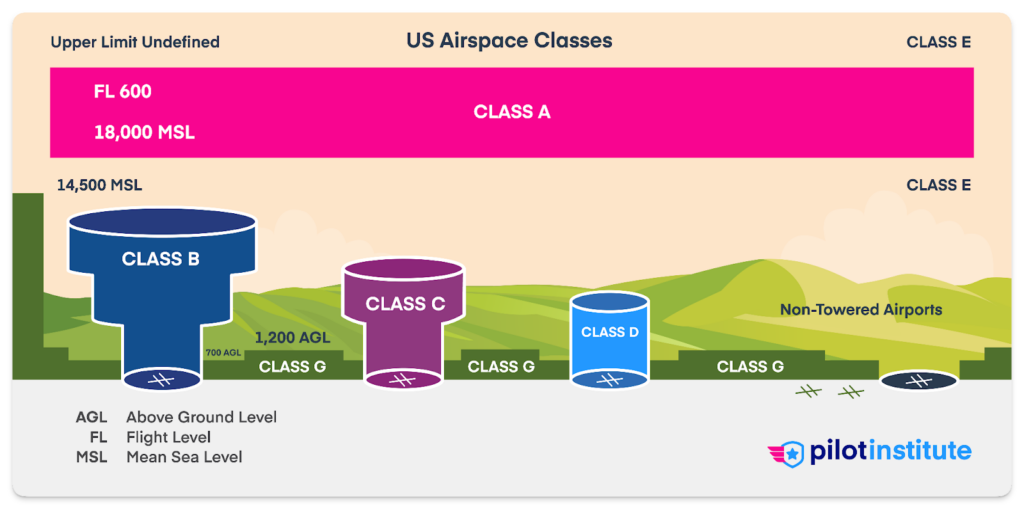

Classes A, B, C, D, and E are controlled airspace. Class G is the only uncontrolled airspace class.

First, let’s explain controlled airspace, starting with Class A.

Class A Airspace

Class A airspace is all around the United States, beginning at 18,000 feet Mean Sea Level (MSL) and going to 60,000 feet MSL.

Since Class A airspace is everywhere, sectional charts don’t depict it.

Aircraft in Class A airspace don’t use feet to express altitude. Instead, they use flight levels. A flight level is pressure altitude expressed in hundreds of feet. For example, 20,000 feet MSL would be flight level 200 (FL200).

All aircraft use the same altimeter setting of 29.92 inches of mercury. This helps aircraft maintain good vertical separation despite local variations in pressure.

Class A airspace is instrument flight rules (IFR) only. You must be on an instrument flight plan and cleared by ATC to enter. You will need a two-way radio, Mode-C transponder, and ADS-B Out. If navigating via VORs above flight level 240, you need distance measuring equipment (DME) or GPS.

The speed limit in Class A airspace is Mach 1.

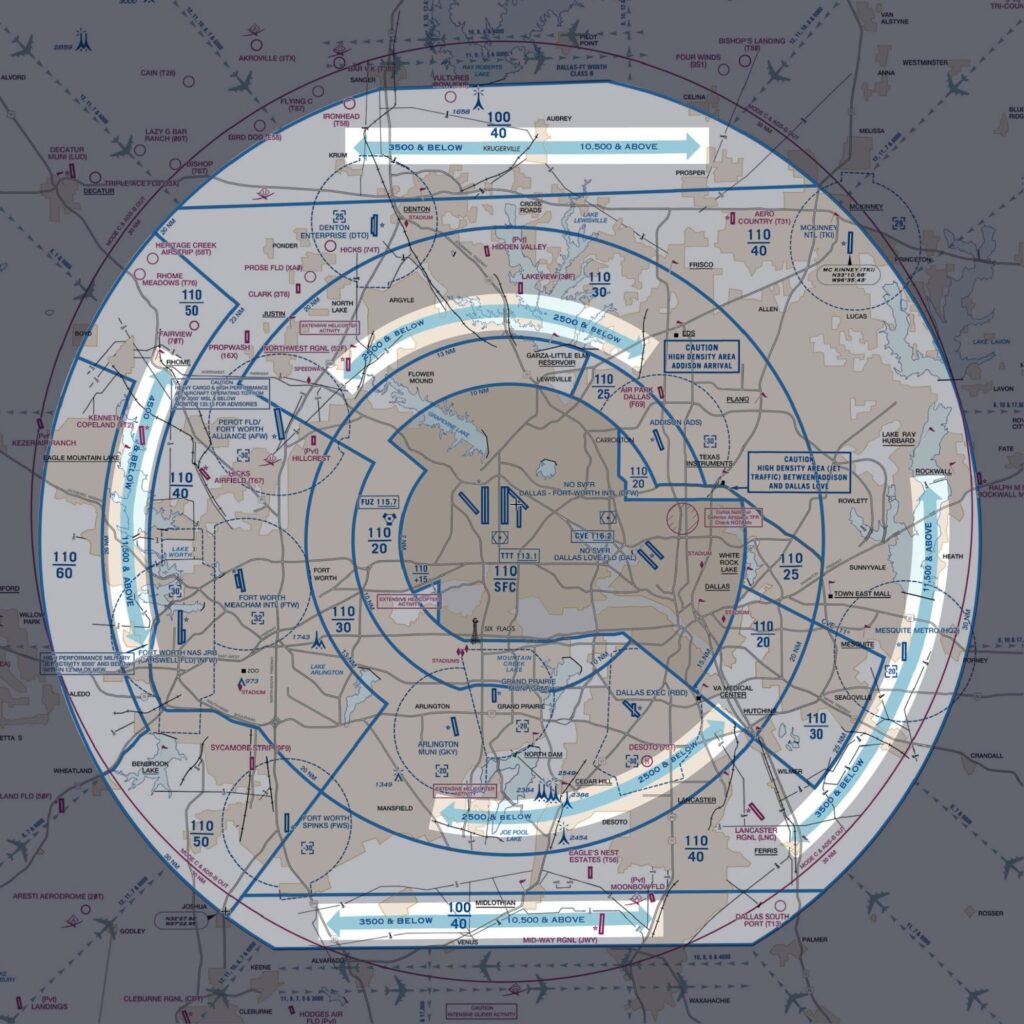

Class B Airspace

You will find Class B airspace around the nation’s 37 busiest airports in major cities.

If you could see Class B airspace in 3D, it would look like an upside-down wedding cake. This is because it consists of several tiers with different altitudes and shapes. Each Class B airspace is custom-made for the airport it surrounds.

Sectional charts depict Class B airspace with solid blue lines. Each sector has an altitude block with a floor and ceiling. The floor is where the airspace starts, and the ceiling is where it ends. The chart lists these in hundreds of feet MSL with a line in between.

The inner sector of Class B airspace starts at the airport surface (indicated by “SFC”). It extends up to around 10,000 feet MSL. Sectors further out will have higher bases, allowing traffic to fly underneath.

A 30-nautical mile Mode C veil surrounds Class B airspace. The sectional chart depicts this boundary as a magenta circle. Inside the circle, all aircraft need an operating Mode-C transponder and ADS-B Out.

The VFR weather minimums require at least 3 statute miles of visibility. The only cloud distance requirement is to stay clear of clouds.

If you’re flying in Class B airspace that starts at the surface, the cloud ceiling must be at least 1,000 feet AGL.

There’s also a speed limit of 200 knots below Class B and through its VFR corridors.

Before entering Class B Airspace, VFR aircraft must receive clearance from ATC.

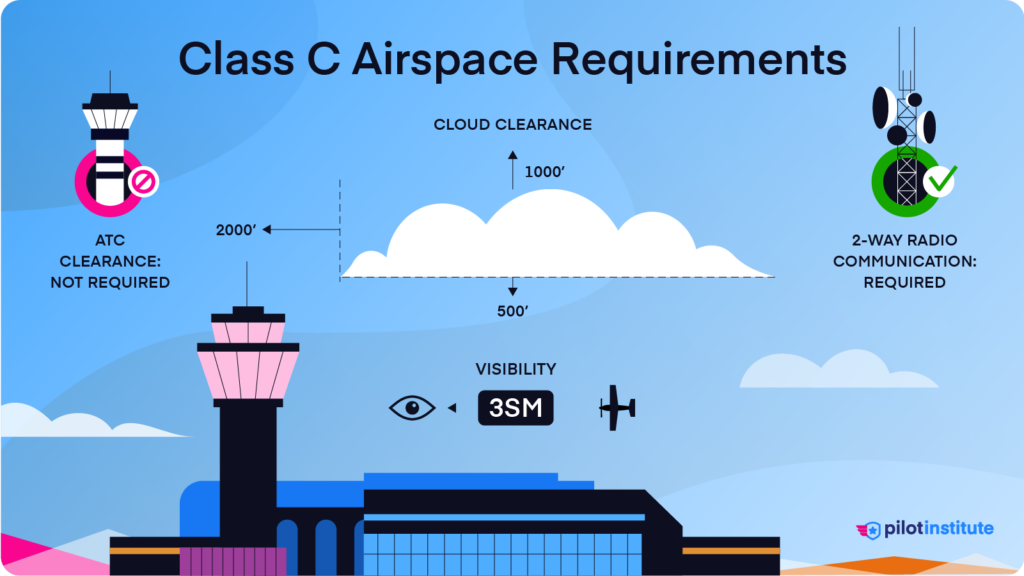

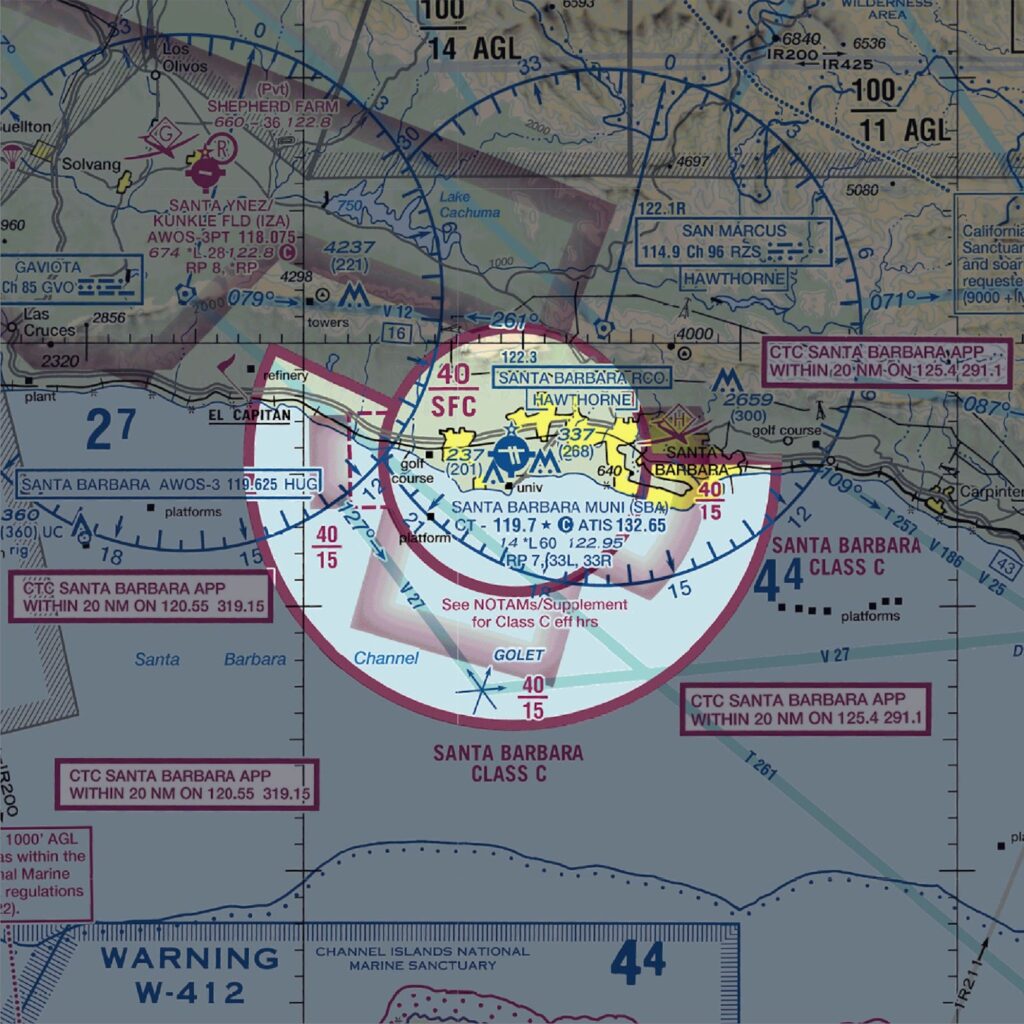

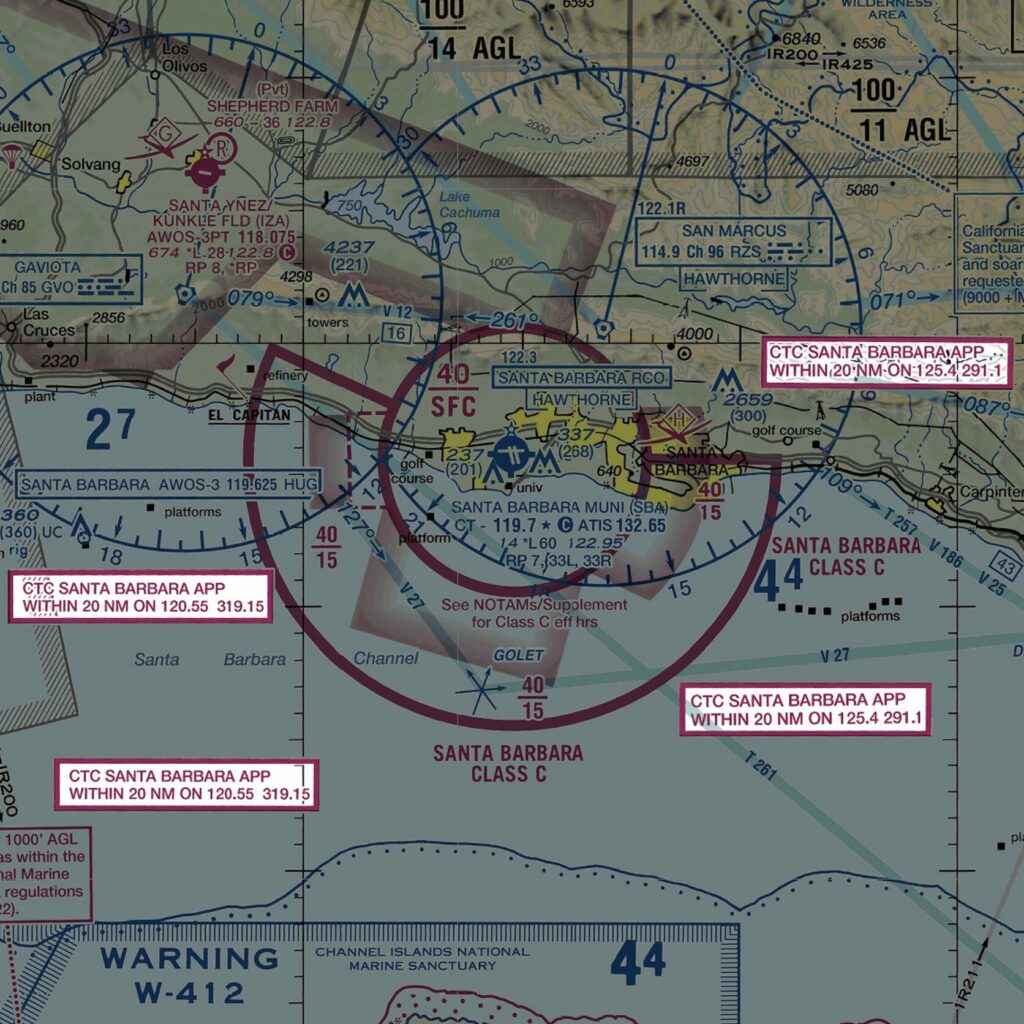

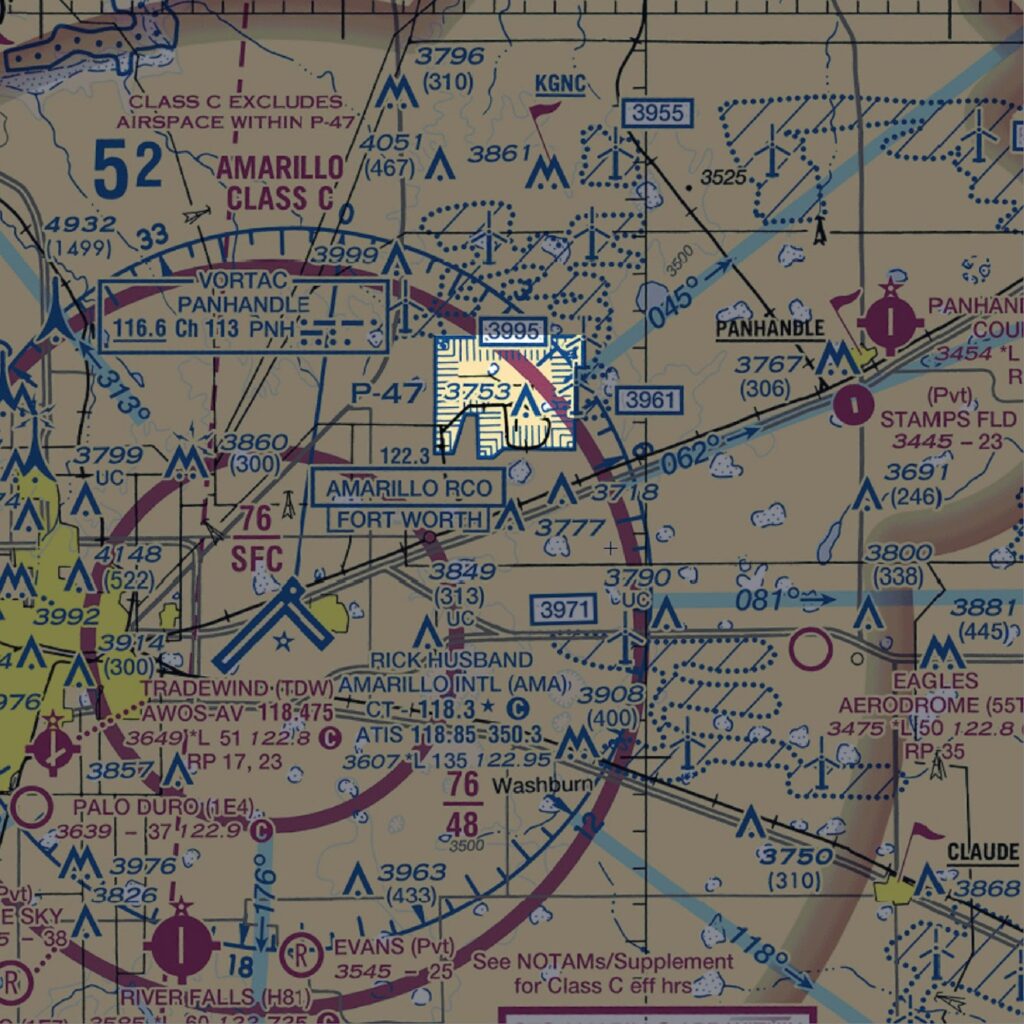

Class C Airspace

Class C airspace exists at large airports that are less busy than Class B airports. You will find them around most medium-sized to large cities.

On the sectional chart, Class C airspace looks similar to Class B airspace, only it’s smaller. It also has magenta lines instead of blue.

The inner core extends from the airport surface to around 4,000 feet AGL and has a radius of 5 nautical miles. The outer shelf has a radius of 10 nautical miles. It starts at 1,200 feet AGL and also extends to 4,000 feet AGL.

Flying VFR in Class C airspace requires at least 3 statute miles of visibility.

Traffic separation isn’t as tightly controlled as in Class B airspace. You’ll need to fly further from clouds to help see and avoid other aircraft. You must fly at least 1,000 feet above, 500 feet below, and 2,000 feet horizontally from clouds.

The speed limit is 200 knots within a 4-nautical mile radius of the airport. Otherwise, the standard limit of 250 knots below 10,000 feet MSL applies.

You don’t need ATC clearance to enter Class C airspace. But, you must establish two-way radio communication first. The approach control frequency is in a white box with a magenta border on your sectional chart.

You will need a Mode-C transponder and ADS-B Out to fly in or over Class C airspace.

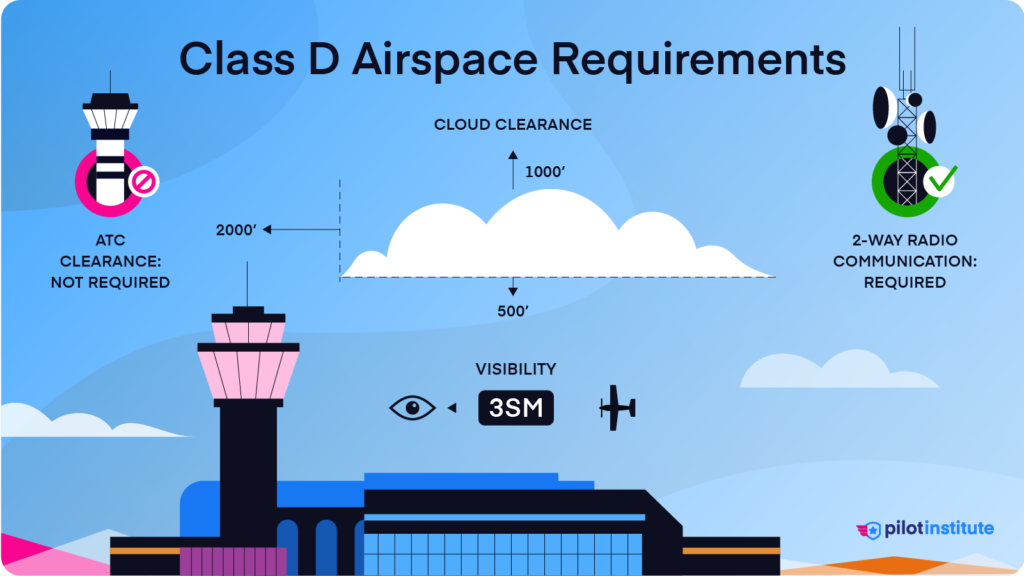

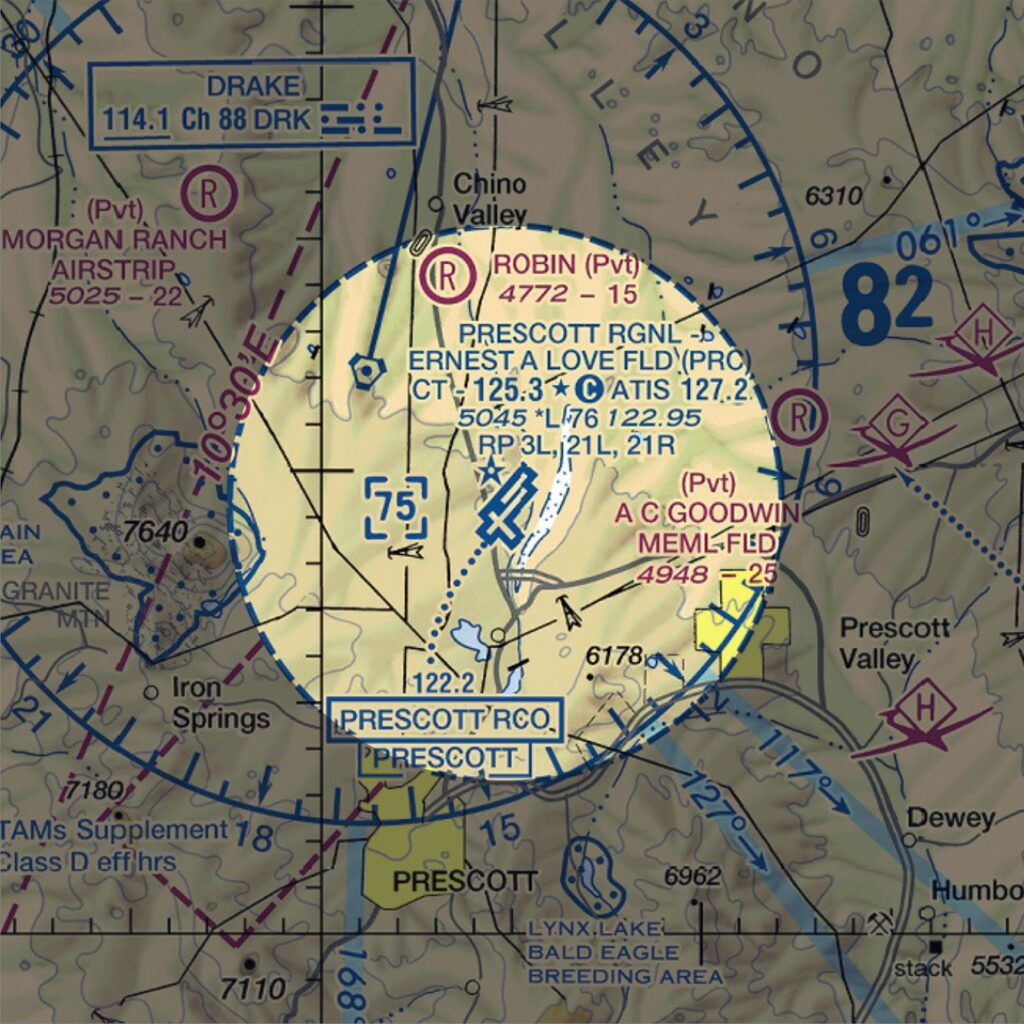

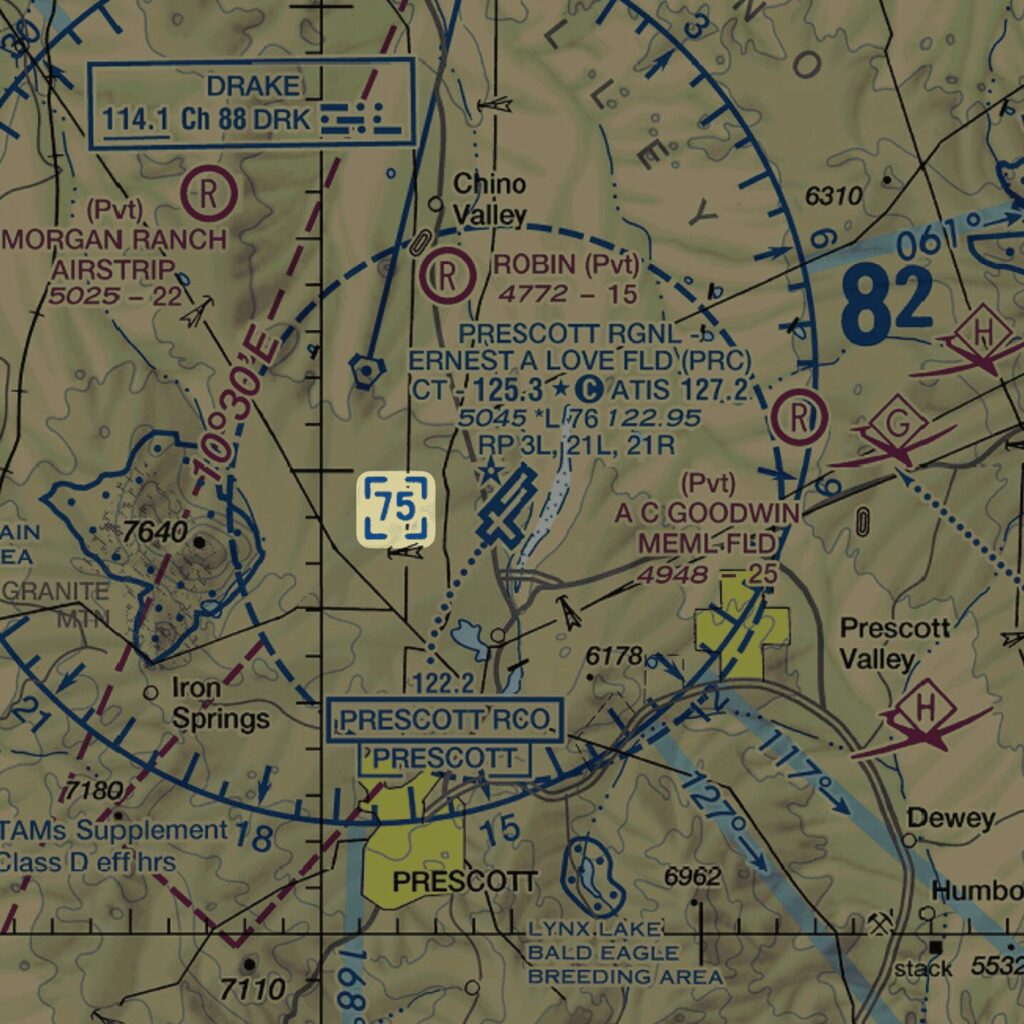

Class D Airspace

You’ll find Class D airspace at airports that are busy enough to have a control tower but not as busy as Class C airspace.

The sectional chart depicts Class D airspace with dashed blue lines. The number in the box indicates the ceiling in hundreds of feet MSL. A minus sign indicates the airspace ceiling goes up to but doesn’t include the listed altitude.

Class D airspace resembles a cylinder with a radius of about 4 or 5 nautical miles. It starts from the airport surface and extends to about 2,500 feet AGL or the airspace floor above it.

The VFR weather minimums are the same as Class C airspace. You need 3 statute miles visibility, and you must stay 1,000 feet above, 500 feet below, and 2,000 feet horizontally from clouds.

Since the airspace is small and doesn’t extend far from the airport, the speed limit is 200 knots.

Before entering Class D airspace, you must establish two-way radio communications with the tower.

Part-Time Class D Airspace

It’s common for control towers at Class D airports to close at night when traffic is slow. Sectional charts identify these part-time control towers with a “*” beside the tower frequency. You’ll find the hours of operation in the Chart Supplement.

When the tower shuts down, the Class D airspace no longer exists.

What airspace goes in its place?

It depends on whether the airport meets weather reporting and communications requirements.

If the airport meets requirements, it becomes surface Class E airspace. It reverts to Class G airspace if it can’t meet those requirements.

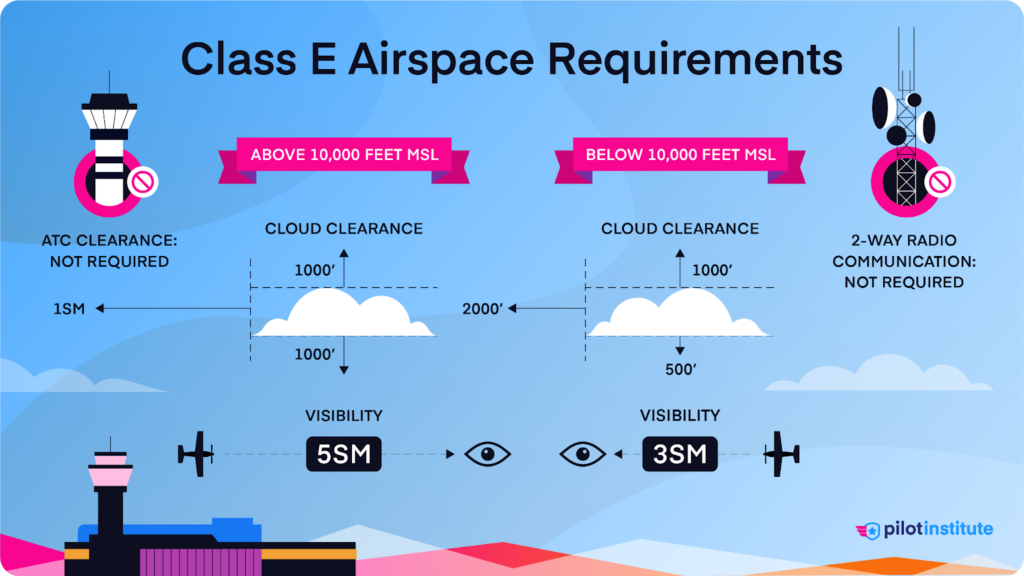

Class E Airspace

Any controlled airspace that is not Class A, B, C, or D is Class E.

Class E airspace fills in the gaps. It allows ATC to manage IFR aircraft outside other controlled airspace.

In most of the country, Class E airspace starts at 1,200 feet AGL, 700 feet AGL, or the surface. Unless the chart indicates otherwise, you can assume Class E airspace always begins at 1,200 feet AGL.

But how do we know where it starts lower?

Look for shaded magenta shapes on a sectional chart. The FAA calls these vignettes. They depict changes in the floor of Class E airspace.

On the “faded” side of the magenta vignette, the floor starts at 700 feet AGL. These are transition areas. They allow ATC to provide services to IFR aircraft flying in or out of airports. These are particularly useful at airports without a control tower. On the “solid” side of the shaded area, Class E starts at 1,200 feet AGL.

You might see a dashed magenta ring inside these transition areas around an airport. This ring indicates that the Class E airspace goes down to the ground.

Remember when we said that Class E starts at 1,200 feet at the highest in most of the country?

Although rare, places exist where Class E starts at 14,500 feet MSL. You will see this represented by a blue vignette. The “faded” side of the vignette represents the typical floor of 1,200 feet AGL. The “solid” side represents a floor of 14,500 feet MSL.

Class E airspace extends up to, but doesn’t include, the floor of Class A airspace at 18,000 feet. It starts again after Class A ends at 60,000 feet and continues to the end of the atmosphere. Even SR-71 pilots can’t avoid Class E airspace!

Aircraft operating under VFR are not required to maintain radio communications with ATC.

There are no Class E entry requirements. But, there are VFR weather minimums.

If you’re below 10,000 feet MSL, the weather minimums are the same as Class C and D airspace. You need 3 statute miles visibility, and you must stay 1,000 feet above, 500 feet below, and 2,000 feet horizontally from clouds.

If you’re above 10,000 feet, the minimums increase to 5 statute miles visibility. You need to stay 1,000 feet above, 1,000 feet below, and 1 statute mile horizontally from clouds.

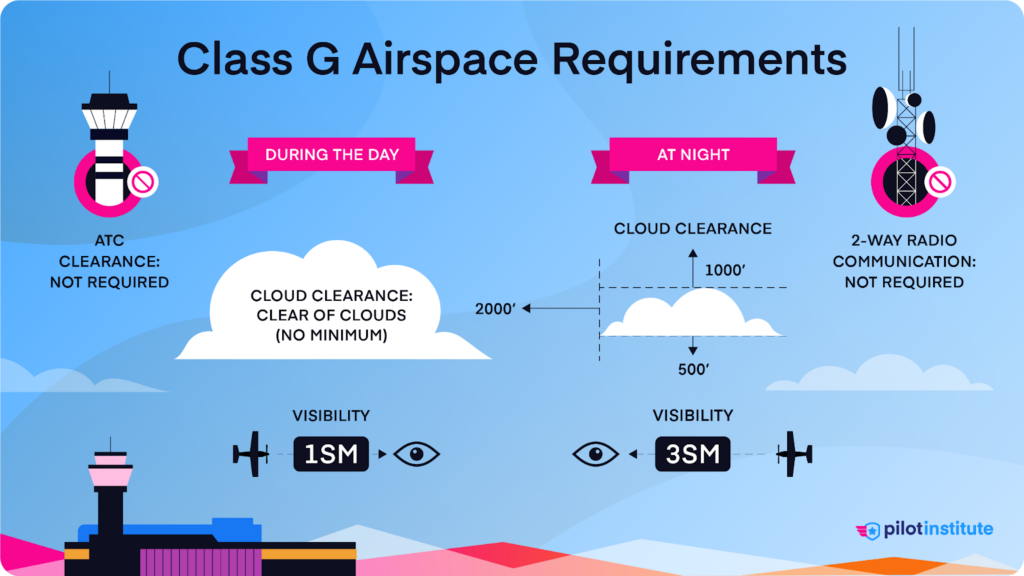

Class G Airspace

Class G airspace is uncontrolled airspace. It exists wherever controlled airspace doesn’t. Class G starts at the surface unless controlled airspace exists on the ground.

You won’t find Class G airspace depicted on the sectional chart, and there are no entry or communication requirements.

Class G VFR weather minimums are somewhat complicated.

If you’re in Class G under 10,000 feet MSL, you need 1 statute mile of visibility during the day and 3 statute miles at night.

Below 1,200 feet AGL during the day, you only need to stay clear of clouds. But at night, the requirements are stricter. You need to stay 1,000 feet above, 500 feet below, and 2,000 feet horizontally from clouds.

What if you’re in the rare Class G that exists under 10,000 feet MSL but over 1,200 feet AGL? In that case, this stricter cloud clearance also applies during the day and night.

Are you flying in Class G airspace over 10,000 feet MSL and 1,200 feet AGL? The requirements match high-altitude Class E. For visibility, that’s 5 statute miles. You must also stay 1,000 feet above, 1,000 feet below, and 1 statute mile horizontally from clouds.

There’s an exception if you fly in the traffic pattern at night within half a mile of the runway. In that case, you only need 1 mile of visibility and to stay clear of clouds. So enjoy your nighttime touch-and-goes!

Special Use Airspace

Special Use Airspace (SUA) has specific rules because of the activities inside it.

If these activities sound mysterious, we will solve the mystery for you.

Let’s start by looking at Restricted areas.

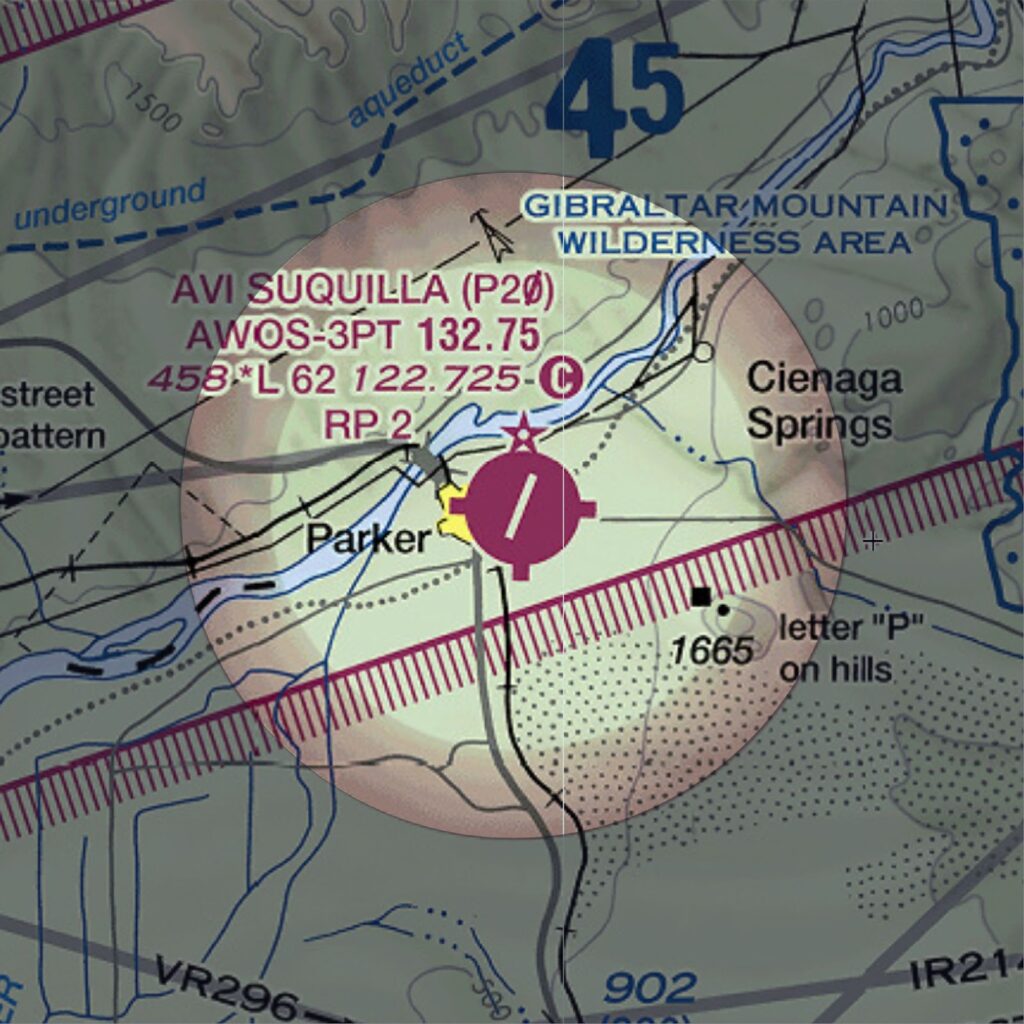

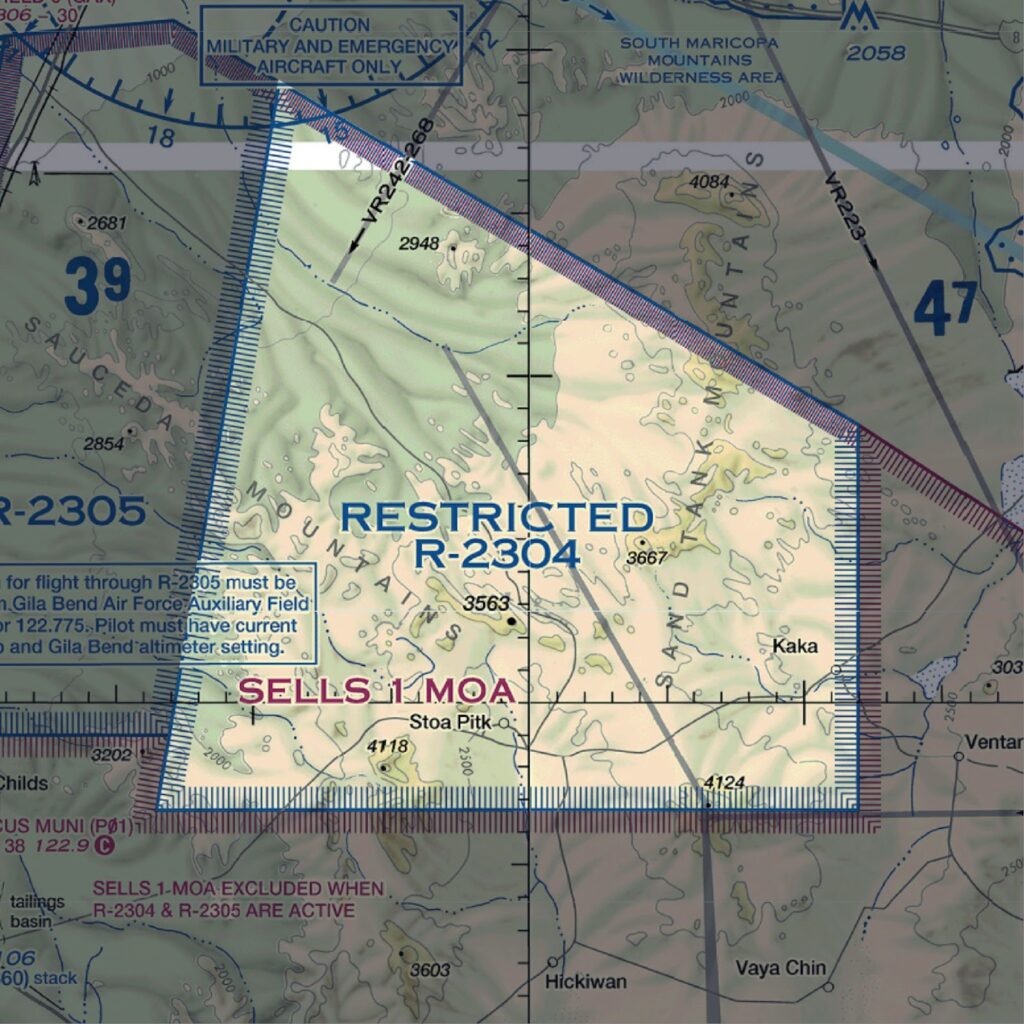

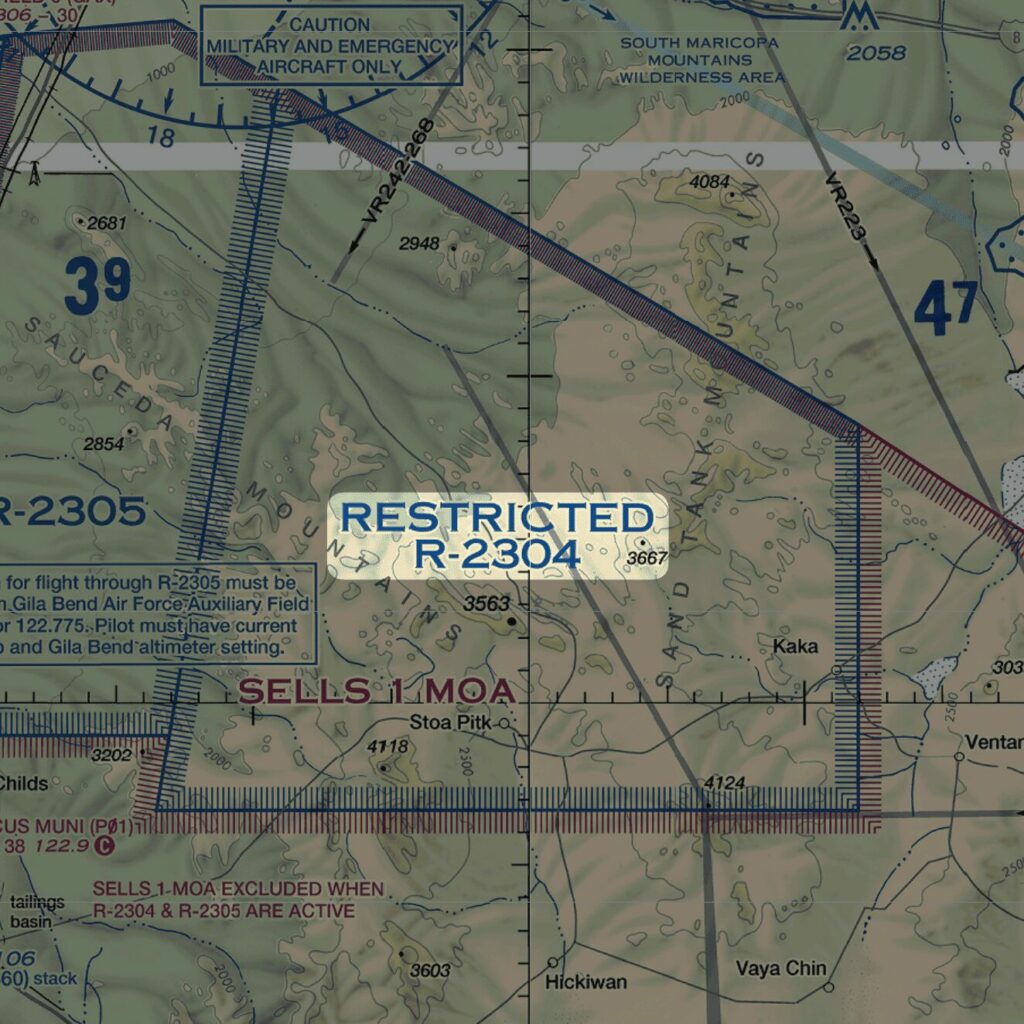

Restricted Areas

Restricted areas contain hazardous activities like artillery firing and guided missile launches. The purpose of Restricted areas is to separate civilian traffic from these activities.

Thankfully, avoiding Restricted areas is easy. Your sectional chart depicts them with a hatched blue border and the letter R followed by a number.

The FAA prohibits pilots from flying through a Restricted area while it’s active. Active means that hazardous activities are currently going on inside. You can find the active hours and affected altitudes on your sectional chart or EFB.

If you’re 100% sure it’s inactive, you can fly through without contacting anyone. But can you be 100% sure? Calling up the controlling agency first is highly recommended. It beats being intercepted by F-16s.

Your sectional chart or EFB lists the controlling agency’s contact information.

Prohibited Areas

Prohibited areas define airspace where aircraft are not permitted. No exceptions. These areas exist for reasons of national security or welfare.

Expect serious repercussions should you stumble into one, possibly including jail time.

Sectional charts depict Prohibited areas with a hatched blue border. They’re identified by the letter P followed by numbers. For example, Prohibited Area P-47 covers a nuclear weapons facility in Amarillo, Texas.

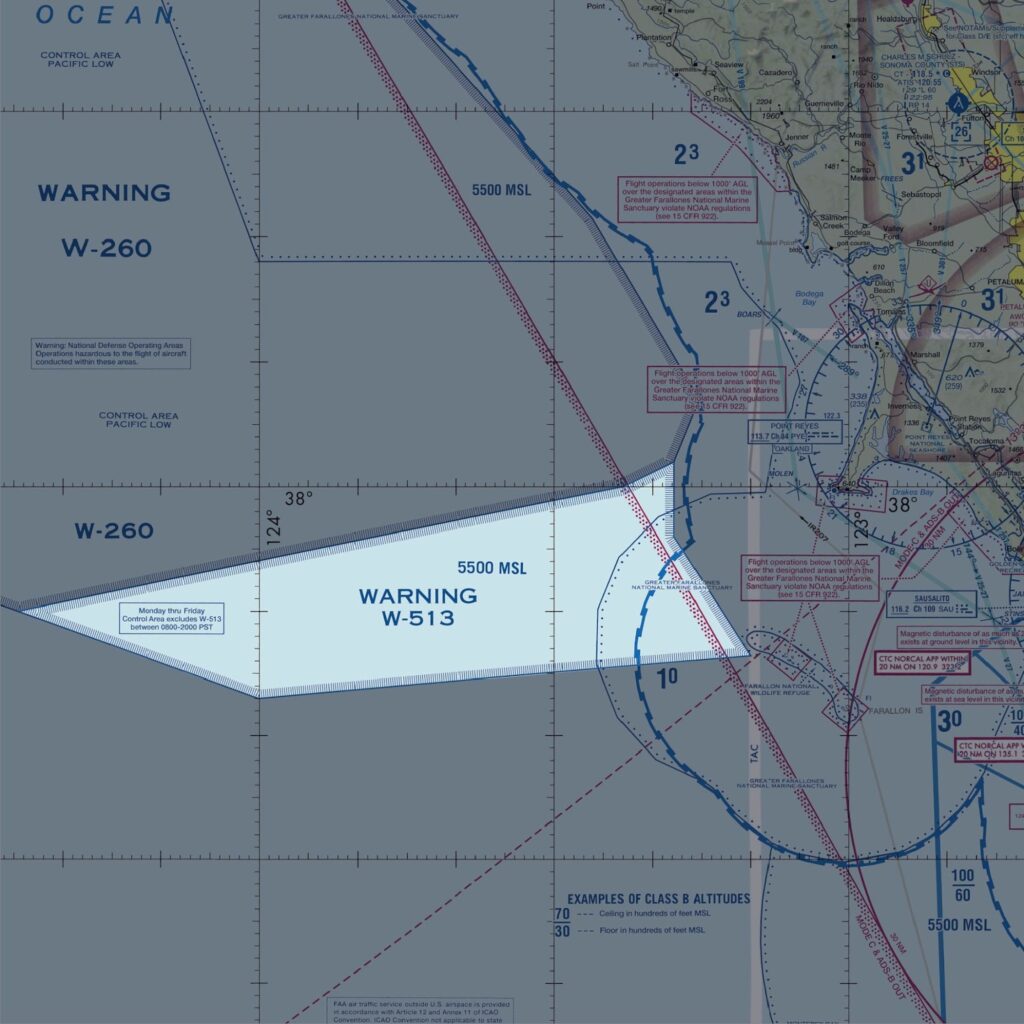

Warning Areas

Warning areas start 3 nautical miles from the U.S. coastline and extend outward. Like Restricted areas, they contain activities hazardous to civil aircraft. High-speed military jets and missile launches are common inside Warning areas.

Sectional charts depict Warning areas with a blue-hatched border. They’re identified by the letter W followed by numbers.

The main difference between Restricted and Warning areas is the location.

The U.S. government doesn’t have sole jurisdiction over open waters. Because of this, they can’t legally stop you from flying into a Warning area.

But as with Restricted areas, flying into a Warning area without contacting ATC first is a bad idea. Check your sectional chart or EFB for the active hours and controlling agency.

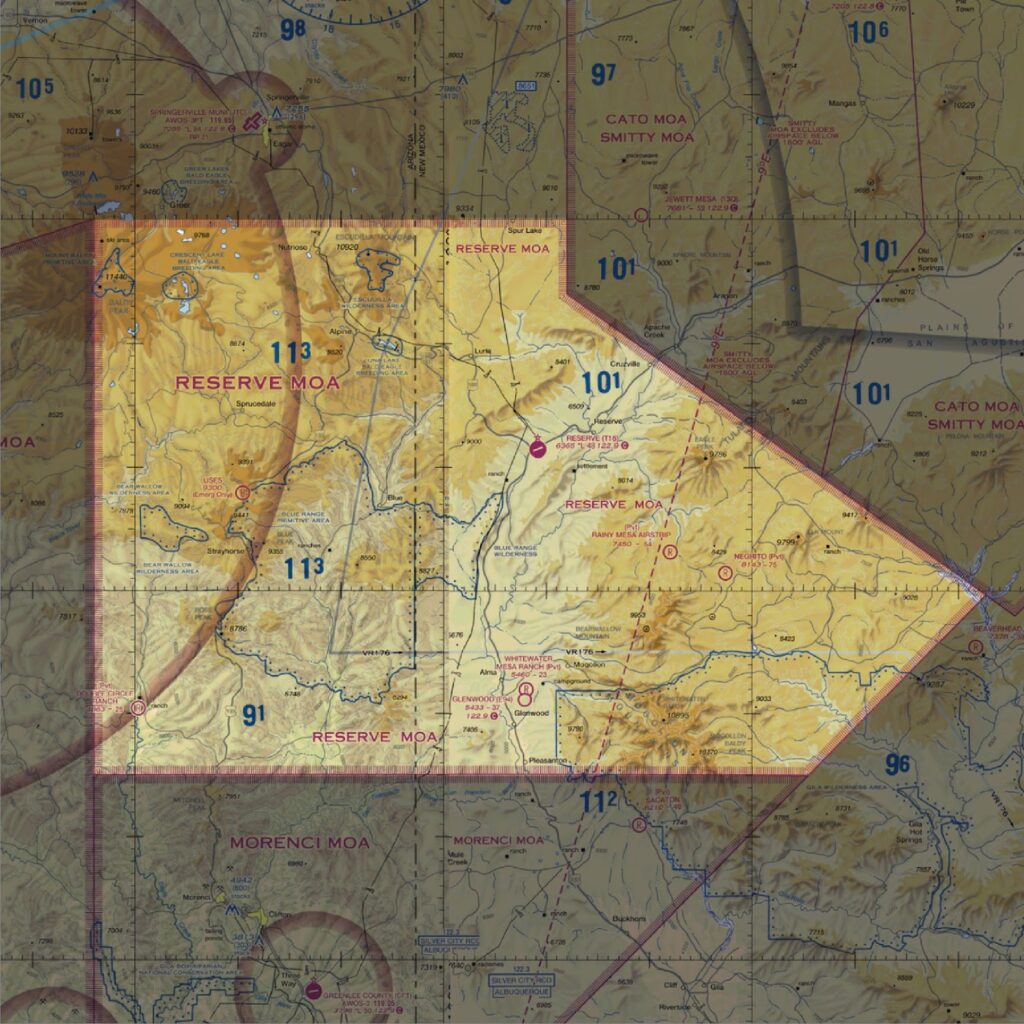

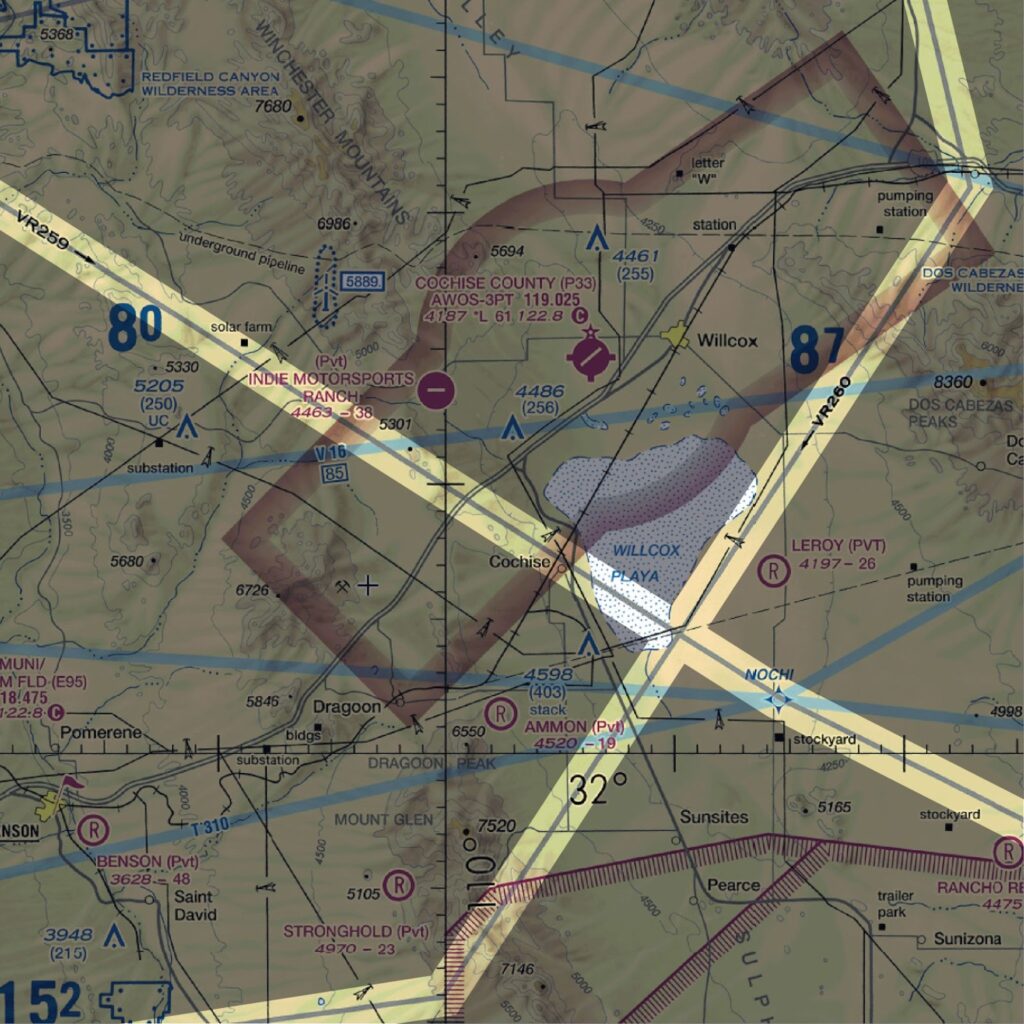

Military Operation Areas (MOAs)

Military operations areas (MOAs) separate military training activities from IFR traffic.

You can legally fly through an active MOA without permission if you’re under VFR. However, doing so could bring you face-to-face with fighter jets flying over 250 knots.

Always call up the controlling agency before entering a MOA.

Sectional charts depict MOAs with a hashed magenta border. You can find the MOA name written inside.

Your chart or EFB will tell you the times of operation and the altitudes affected.

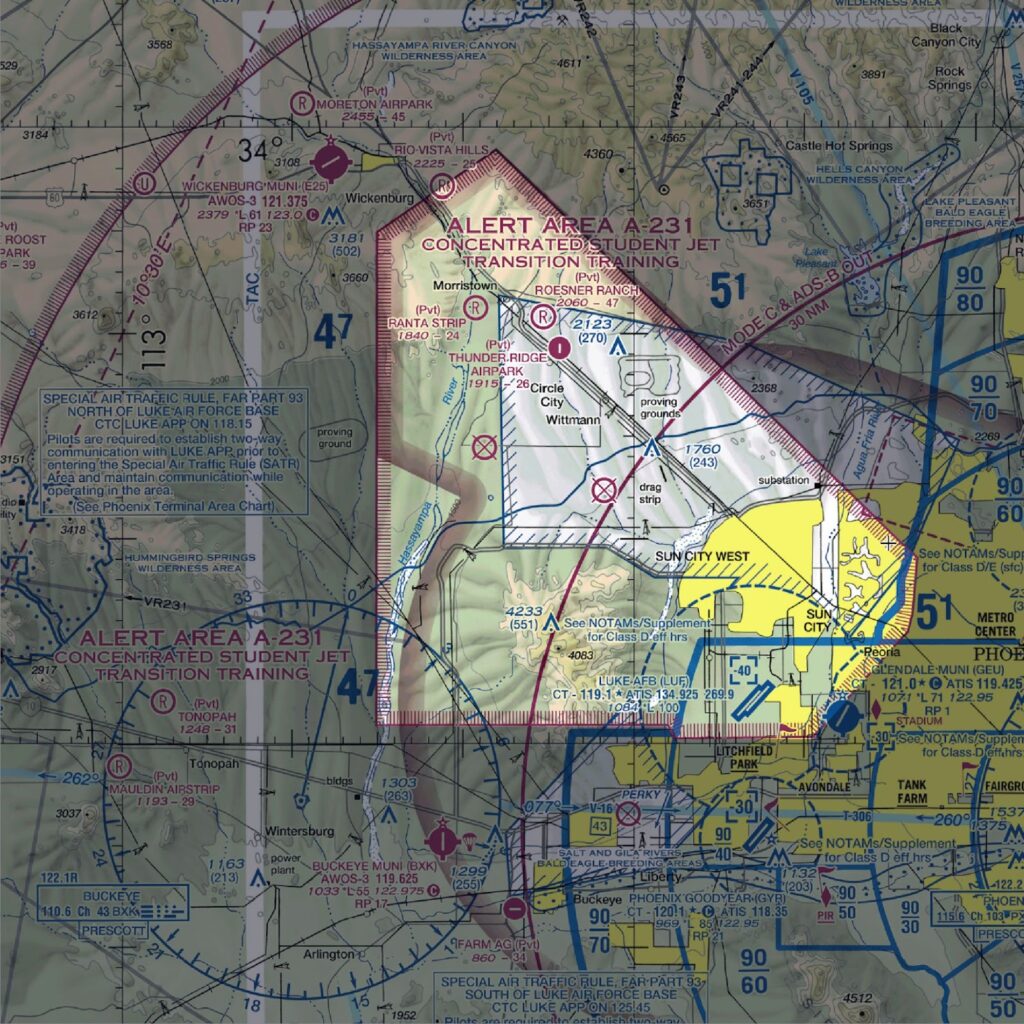

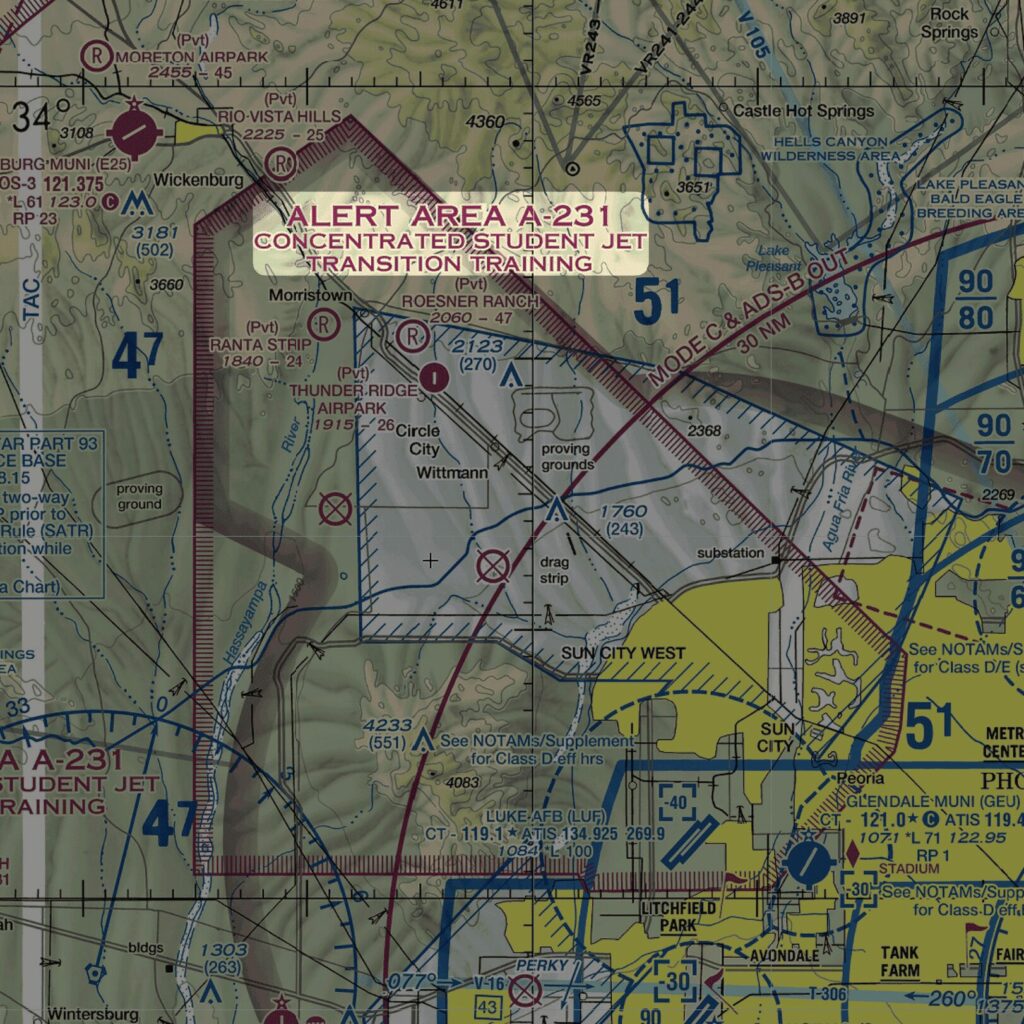

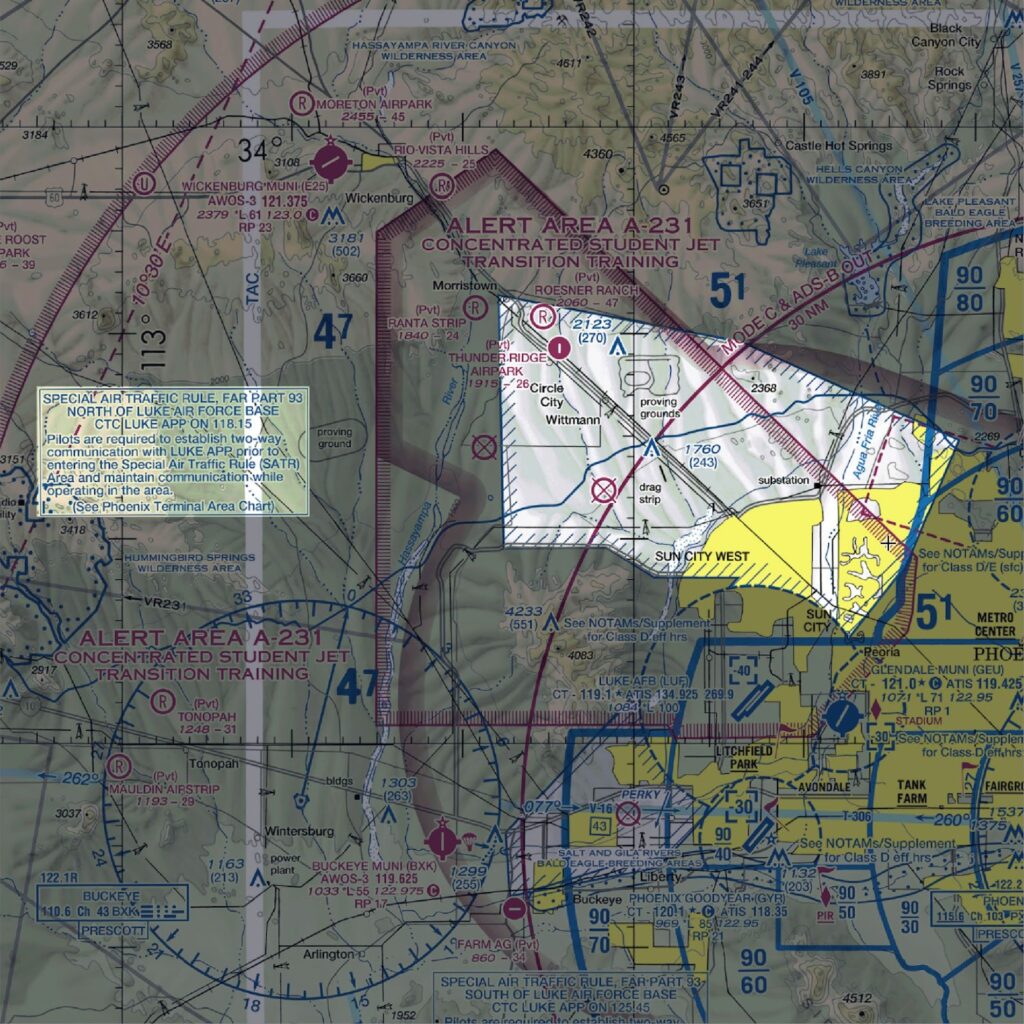

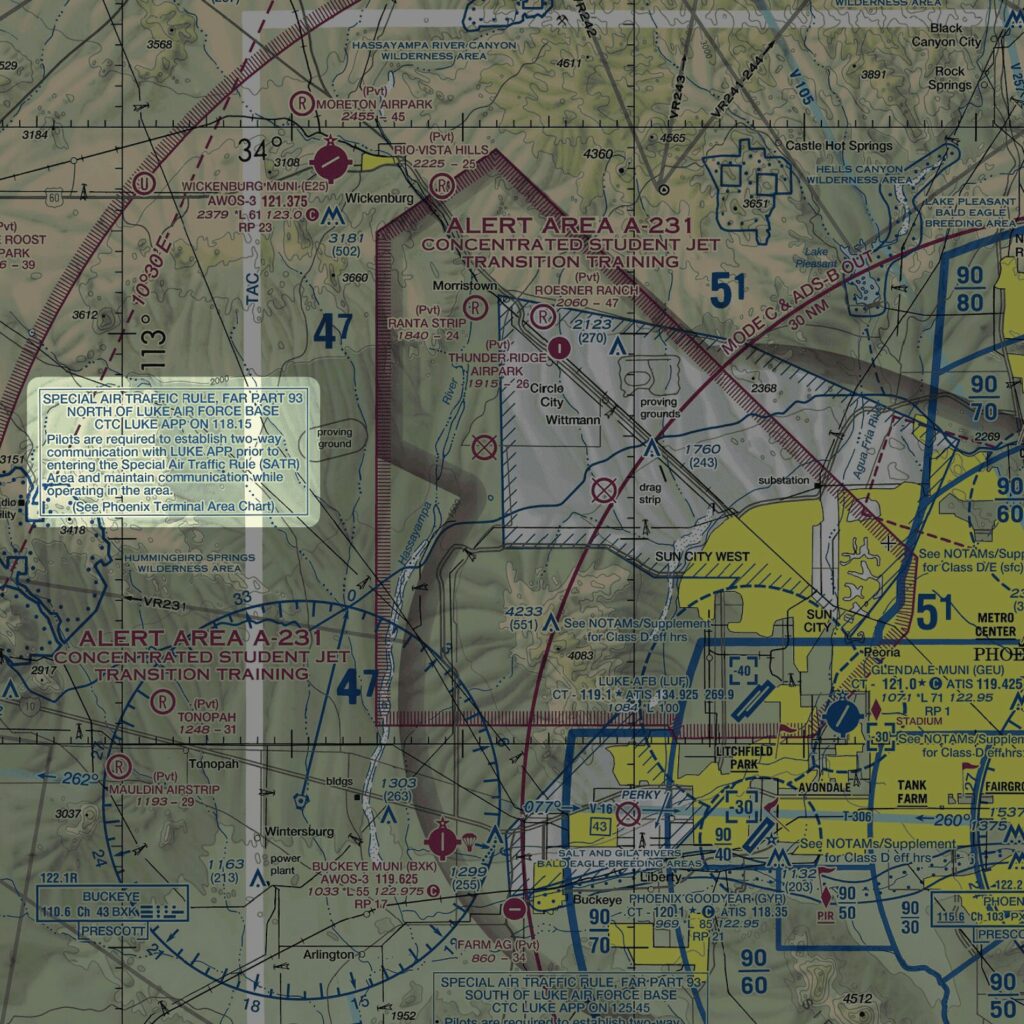

Alert Areas

Alert areas inform pilots that the area may contain a high volume of aerial activity. Intensive flight training areas are a common reason for Alert area designation.

Sectional charts depict Alert areas with a hatched magenta border and an “A” followed by a number.

There are no requirements to enter Alert areas. The FAA simply wants you to pay special attention while flying in these areas.

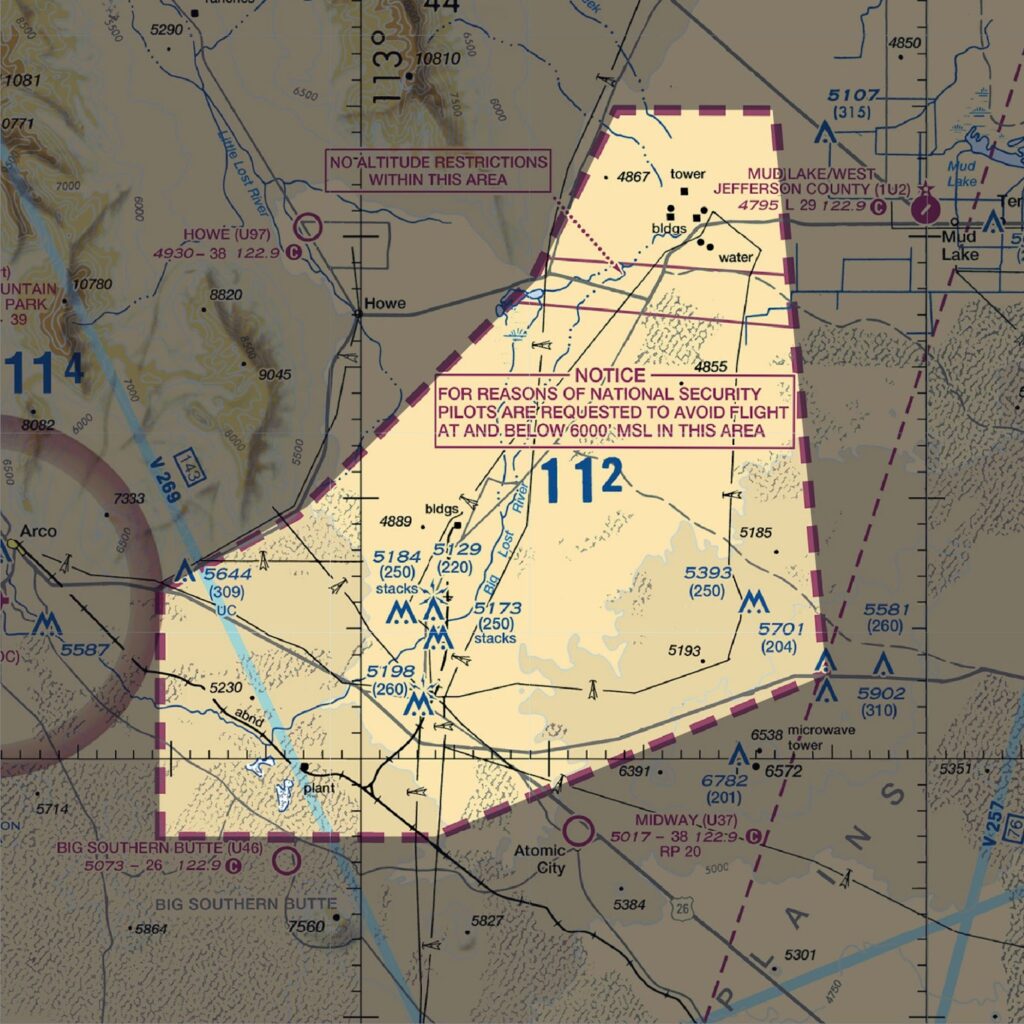

National Security Areas (NSAs)

National Security Areas (NSAs) protect the security and safety of ground facilities. For example, an NSA may cover a nuclear power plant or a military weapons research facility.

Sectional charts depict NSAs with thick, dashed magenta lines. There will be a notice listed nearby that includes specific altitude restrictions.

The FAA doesn’t wholly prohibit flight in NSAs. However, they request pilots avoid flying through them.

A Notice to Air Mission (NOTAM) may temporarily prohibit flight in an NSA. Check NOTAMs and contact ATC before flying through an NSA.

Other Airspace Areas

Several types of airspace don’t fit into a specific category. The FAA has grouped them into Other Airspace Areas.

Don’t let the generic name fool you. These areas are critical to know.

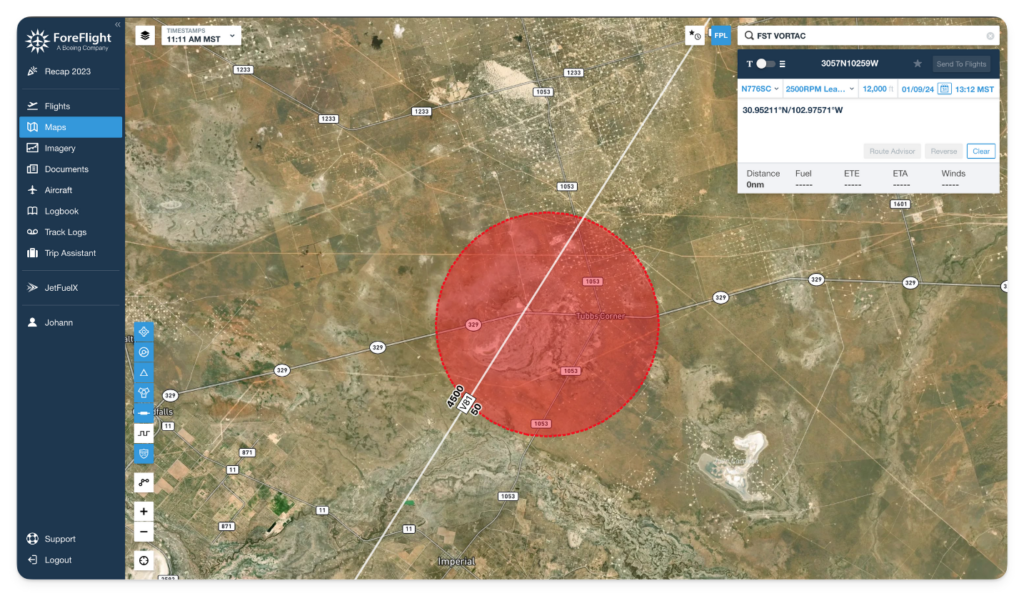

Temporary Flight Restrictions (TFRs)

Temporary Flight Restrictions (TFRs) prohibit or restrict aircraft activity in a designated area.

Think of TFRs as pop-up Prohibited or Restricted areas. They are active for specified dates and times.

Reasons for TFRs include:

- Providing a safe environment for the operation of disaster relief aircraft.

- Protecting the President, Vice President, or other public figures.

- Protecting airspace for space agency operations.

The FAA creates TFRs via NOTAM. As a pilot, it’s your responsibility to research any TFRs along your route before taking off. You can get into a lot of trouble by accidentally flying into one.

Unless related to national security, you won’t find TFRs printed on sectional charts. Thankfully, EFBs are excellent at overlaying them on the map.

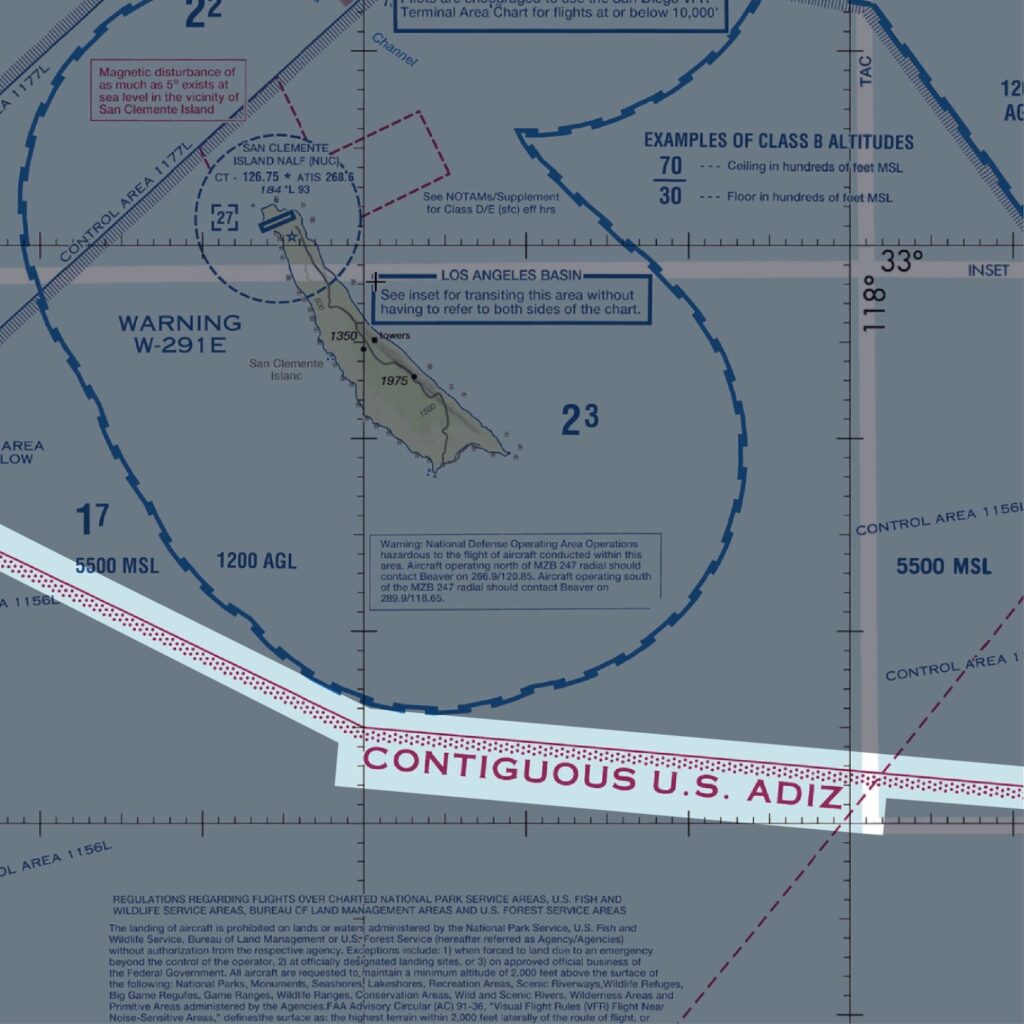

Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ)

The Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) surrounds the country’s perimeter. The ADIZ protects against incursions from unknown aircraft into the country.

If you’re flying through an ADIZ, you must be on an IFR or defense VFR flight plan and be in contact with ATC. The government treats unidentified aircraft entering the ADIZ as possible threats. Unauthorized entry into an ADIZ might result in interception by military aircraft.

Sectional charts depict ADIZ boundaries with a magenta line with dots.

Military Training Routes (MTRs)

Military Training Routes (MTRs) are routes that military aircraft fly during training exercises. MTRs allow military aircraft to exceed the 250-knot speed limit below 10,000 feet. Keep a close eye on traffic if you fly through one.

Sectional charts depict them as gray lines with two letters followed by numbers.

IFR routes are under ATC control and include the letters IR. VFR routes include the letters VR and are not ATC-controlled. A three-digit number means the route has at least one leg above 1,500 feet AGL. Four digits indicate the route stays entirely at or below 1,500 feet AGL.

VFR Flyway

VFR flyways are VFR flight paths around and under busy Class B terminal areas. They’re not mandatory, but the FAA recommends you use them. They help VFR pilots avoid accidentally entering Class B airspace without clearance.

You can find VFR flyways depicted on Flyway Charts (FLY).

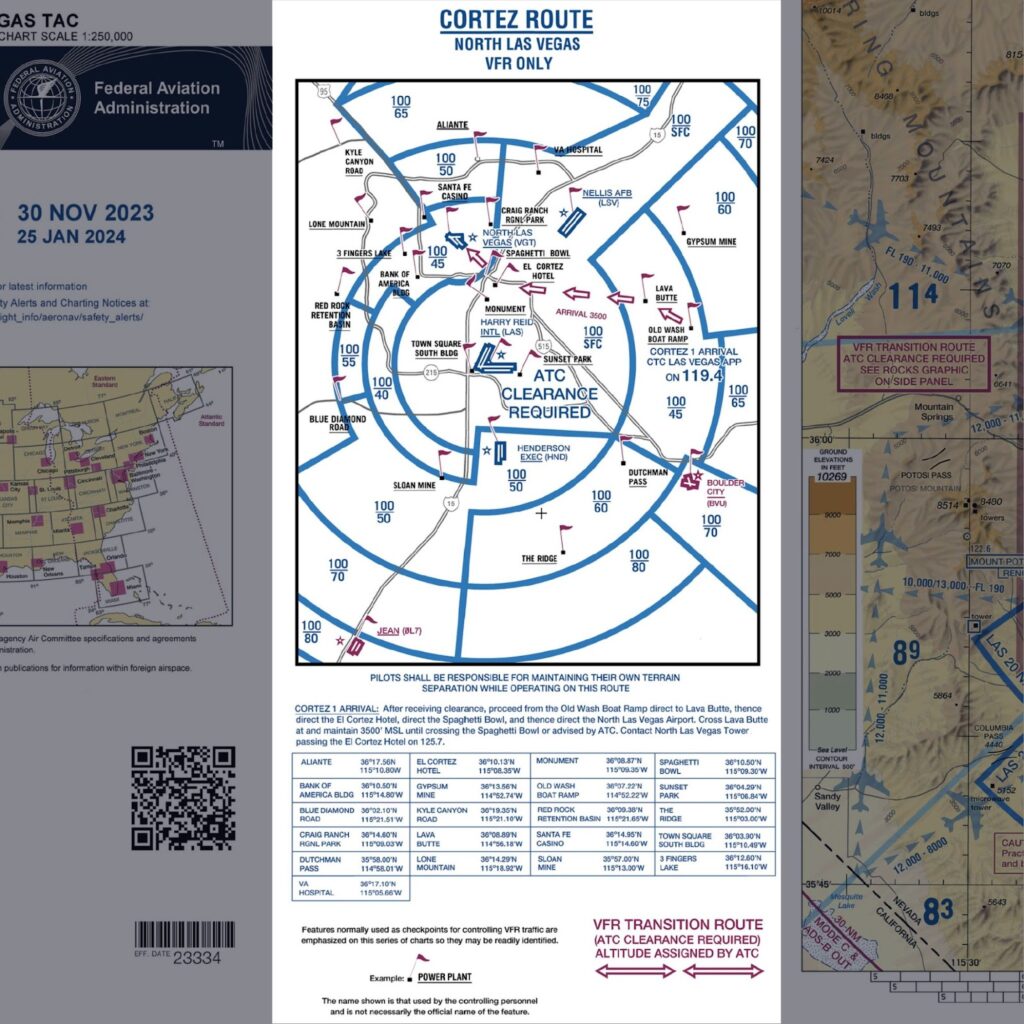

VFR Transition Routes

VFR flyways can help you fly around Class B airspace. But what if you want to fly VFR through Class B airspace?

Some Class B airports have established VFR transition routes. These routes keep VFR traffic along predictable paths in the busy Class B airspace.

Since you will be flying inside Class B airspace, you will need ATC clearance to use a VFR Transition Route.

You can find them depicted on Terminal Area Charts.

Terminal Radar Service Areas (TRSA)

Terminal Radar Service Areas (TRSAs) exist at certain Class D airports.

A TRSA is similar to approach control for a Class B or C airport. They allow ATC to provide pilots with separation and sequencing.

Unlike with Class B and C approach control, TRSAs are voluntary for VFR pilots. However, TRSAs provide extra traffic safety, so there’s little reason not to call them up.

Sectional charts depict TRSAs with thick, solid gray lines.

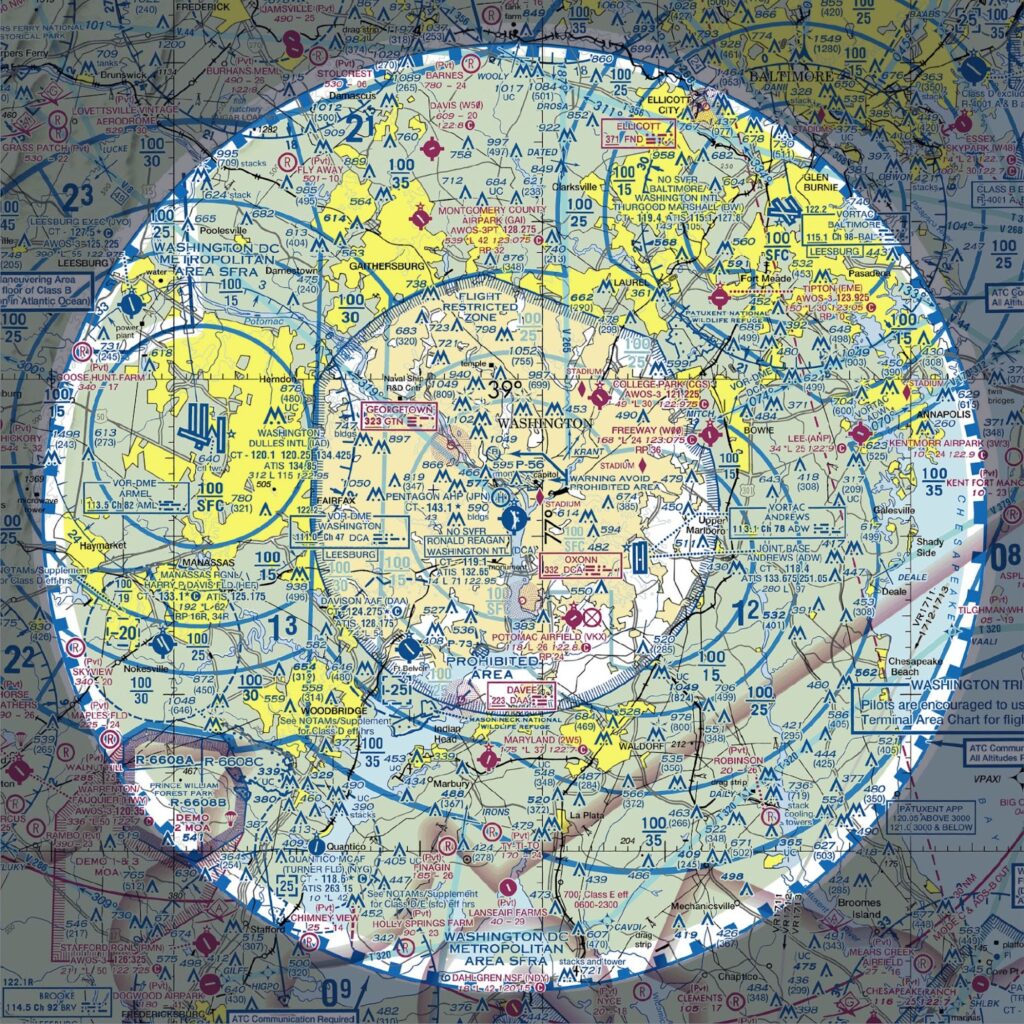

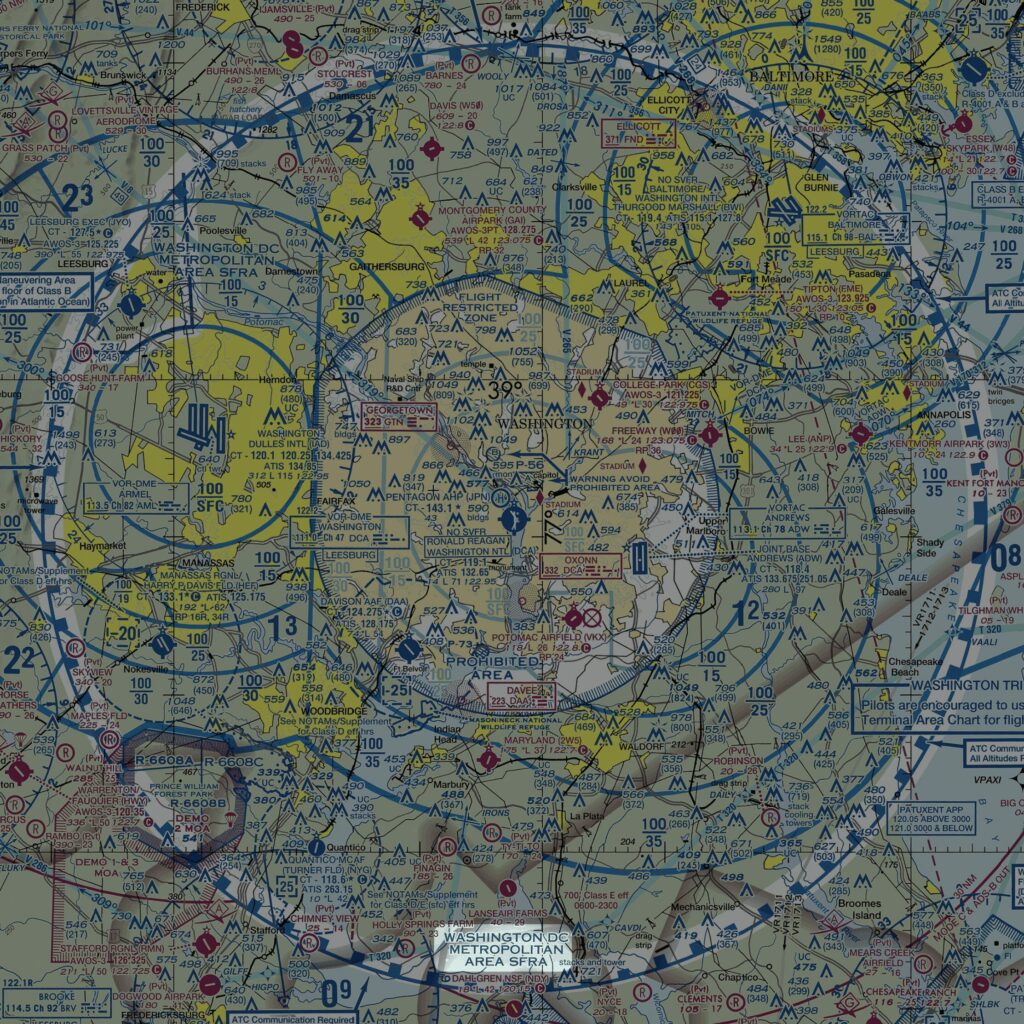

Special Flight Rules Areas (SFRAs)

Plan on flying in locations like Washington D.C. or New York City’s Hudson Corridor? You will need to know about Special Flight Rules Areas.

Special Flight Rules Areas (SFRAs) define airspace where aviation regulations differ from normal. They exist for security or safety reasons.

Flying in these areas requires learning the appropriate Special Air Traffic Rules. You might also need to take an online training course first. Some SFRAs require pilots to file a special flight rules flight plan before entering.

You can find the rules for each SFRA in 14 CFR Part 93.

Sectional charts depict SFRAs with blue lines with “teeth” pointing inward.

Special Air Traffic Rules Areas (SATRs)

Special Air Traffic Rules (SATR) Areas exist where air traffic rules for the area are not standard. They are similar to SFRAs.

Sectional charts depict SATR areas with a cross-hatched blue border. A nearby box will tell you where to find the applicable rules.

You can find SATR area and SFRA regulations in 14 CFR Part 93.

Conclusion

Now that you have a solid understanding of airspace definitions, it’s time to see them in action.

How?

By listening to ATC.

Read this article on how to listen to ATC online to get started.