-

Key Takeaways

-

Understanding Flight Altitude

- Altitude: MSL vs. AGL and Flight Levels

- Why Do Airplanes Fly So High?

-

Typical Cruising Altitudes for Different Aircraft

- Commercial Airliners

- Private Jets

- Military Aircraft

- General Aviation and Small Airplanes

-

Factors Affecting Flight Altitude

- Aircraft Performance and Limitations

- Atmospheric Conditions

- Air Traffic Control and Airspace Structure

-

Altitude Measurement and Flight Levels

- Reduced Vertical Separation Minimum (RVSM)

-

Limitations and Challenges at High Altitudes

- Aircraft Structural and Engine Limits

- Passenger Safety and Comfort

- Environmental Factors

-

Factors Influencing Altitude Changes During Flight

- ATC Coordination

-

Conclusion

Ever looked out an airplane window and wondered how high you’re really flying? Well, there’s more to it than just a number on the altimeter.

Altitudes affect your airplane’s performance and even passenger health. That’s why pilots work hard to balance every variable in their aircraft.

In this article, we’ll uncover why airplanes cruise where they do and how altitude decisions are made. To help with that, we’ll take a look at what goes on behind the scenes to keep every flight reliable.

Key Takeaways

- Altitude can be measured in terms of AGL, MSL, or flight level (FL).

- Service ceiling is the maximum altitude with a 100 ft/min climb at max power. The absolute ceiling is the absolute maximum altitude.

- Commercial airliners typically cruise between 30,000 and 40,000 feet for efficiency and safety.

- Single-engine piston aircraft have service ceilings of around 14,000 and 18,000 feet.

Free Private Pilot Study Sheet

Grab a printable PDF that highlights must-know PPL topics for the written test and checkride.

- Airspace at-a-glance.

- Key regs & V-speeds.

- Weather quick cues.

- Pattern and radio calls.

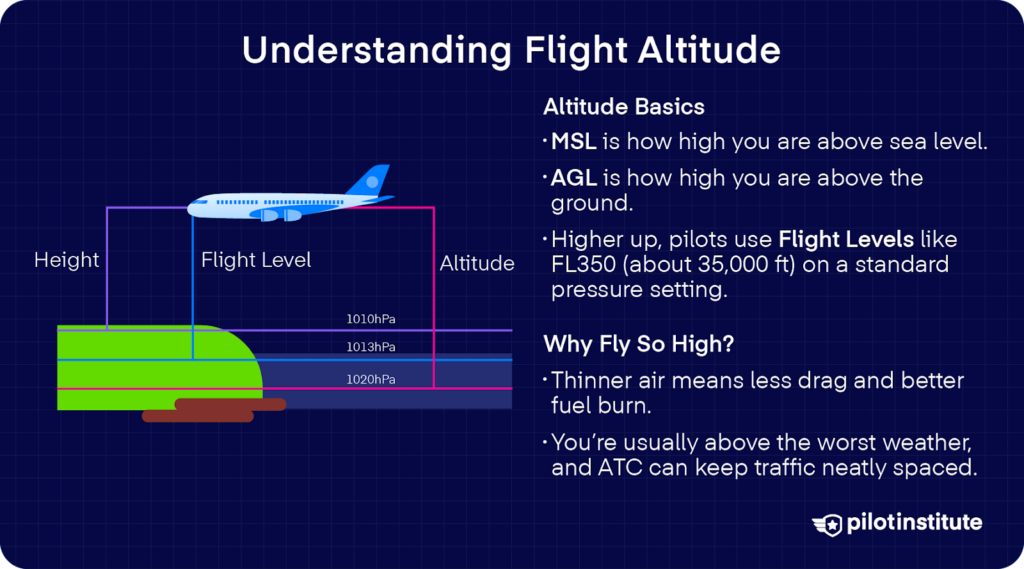

Understanding Flight Altitude

Altitude: MSL vs. AGL and Flight Levels

Altitude can be expressed in many ways, but most often, people are talking about either above Mean Sea Level (AMSL/MSL) or Above Ground Level (AGL).

MSL is the height of the aircraft above the average sea level. AGL, on the other hand, is the aircraft’s distance from the ground directly beneath it.

Just to show you how that’ll look, if you’re flying at 10,000 ft MSL over terrain at 4,000 ft, your altitude AGL would only be 6,000 ft.

It’s important to know the different types of altitude as well, such as pressure altitude and density altitude.

But there’s another way pilots and air traffic controllers (ATC) express altitude. In en-route operations above a certain altitude (like in Class A airspace), we use the concept of Flight Levels (FL).

Flight Levels are altitudes expressed in hundreds of feet, based on a standard pressure setting of 29.92 inches of mercury (inHg) in the U.S., rather than local barometric pressure.

For instance, FL350 corresponds to approximately 35,000 ft, based on the standard pressure setting.

But why use a different system at higher altitudes? It’s more efficient for everyone to use a standard pressure reference. Flight levels make it easier to space every aircraft in that high-altitude block using the same baseline. That, in turn, makes vertical separation more reliable.

Why Do Airplanes Fly So High?

Well, flying high just has a lot of advantages. When you climb higher, the air gets thinner, which means less air resistance or drag.

With less drag acting on the aircraft, it takes less fuel to maintain cruise speed. Also, thin air means the engines and aerodynamic surfaces can perform more efficiently.

You’ll also be less likely to run into weather systems like storms and widespread turbulence. The environment above major weather systems tends to be smoother and more stable.

High altitudes allow for structured traffic flows. When aircraft cruise at designated altitudes or flight levels, controllers can separate eastbound and westbound traffic in a more systematic way.

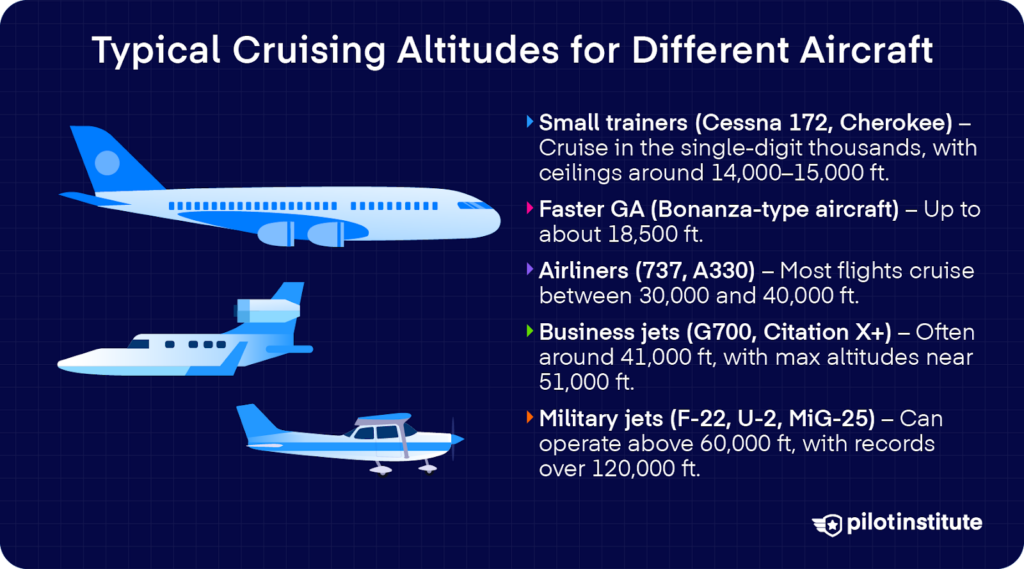

Typical Cruising Altitudes for Different Aircraft

Commercial Airliners

Most of us have flown in an airliner and looked out the window mid-cruise to see clouds spread out underneath us. That’s when we realized that we’re flying higher than we imagined, but just how high, exactly?

When you fly on a major airline, the aircraft is commonly cruising somewhere between 30,000 and 40,000 feet above sea level. For example, the Boeing 737-800 typically cruises between 33,000 and 41,000 feet! The Airbus A330-200 flies around the same altitude, at 31,000 to 41,000 feet.

Shorter routes or heavily loaded aircraft may cruise a bit lower, but the sweet spot for long-haul efficiency is in that 30,000-to-40,000-feet band.

Private Jets

For those who enjoy (and can afford to) cruise in luxury, private jets allow you to fly comfortably and quickly, but that isn’t to say they aren’t capable of soaring above the clouds, either.

The cabin is one of the G700’s headline items. It’s very long and wide, and it’s configurable into multiple living areas.

How high does it fly? It usually cruises at around 41,000 ft without breaking a sweat, but its maximum cruise altitude can go as high as 51,000 ft!

Then, there’s the Cessna Citation X+. You’ll notice its strongest selling points right away: very high cruise speed, a long-leg range for a mid-size jet, and modern avionics that make operating it efficient.

And that’s to say nothing of its climb capabilities. Same as the G700, it can reach altitudes of up to 51,000 ft.

Military Aircraft

Military aircraft operate in a different league. Military aircraft often fly much higher than civilian traffic, depending on mission and platform. These flights challenge the limits of altitude for surveillance or tactical advantage.

For instance, the F‑22 Raptor has a service ceiling of around 65,000 feet (19,812 meters). Meanwhile, the U‑2 Dragon Lady reconnaissance aircraft regularly flies at or above 70,000 feet (about 21,000 meters).

But if we’re talking about record-breaking altitude capabilities, nothing has beaten Soviet pilot Alexandr Vasilievich Fedotov and his MiG-25.

On August 1977, Fedotov broke a world record in Class C of Powered Aeroplanes (for planes that take off under their own power) when he climbed to 123,523 feet (37,650 meters) in his MiG-25!

General Aviation and Small Airplanes

Most pilots have started their careers in small and humble general aviation airplanes. For instance, the classic Cessna 172 lists a service ceiling of around 14,000 ft. The slower-breathing piston engine simply can’t maintain sea-level power indefinitely as the air thins.

Similarly, the Piper Cherokee PA-28-140 has a service ceiling of 15,000 ft. In even richer light aircraft, you’ll find the Beechcraft Bonanza A36, which is certified to about 18,500 ft in its standard form.

That’s still far below the altitudes jets or turboprops regularly use. But even if piston engines aren’t really made for flying high, when it comes to shaping the next generation of pilots, they get the job done.

Factors Affecting Flight Altitude

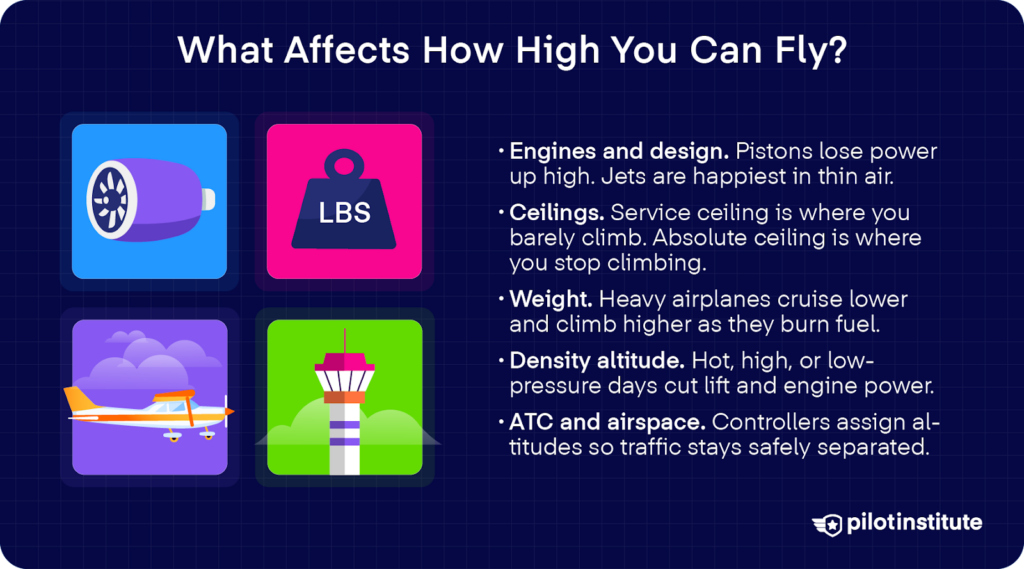

Now, let’s explore the key factors that determine how high an aircraft can fly. What are they capable of, and what are the limitations of climb in real-world operations?

Aircraft Performance and Limitations

First of all, engine type and overall performance matter a lot for altitude. Piston-driven engines tend to lose efficiency as you climb, because as air becomes thinner, there’s less oxygen available for combustion. That means the engine produces less power at higher altitudes unless it’s turbocharged or supercharged.

Jet or turbine engines, on the other hand, are designed to function much better in thinner air. That’s part of the reason why airliners cruise higher and more efficiently.

Performance Ceiling

Alongside engine type, you have two important altitude limits: the service ceiling and the absolute ceiling.

The service ceiling is defined as the maximum density altitude at which an aircraft can still maintain a climb rate of about 100 feet per minute under maximum continuous power and clean configuration.

As you can imagine, your engine’s already starting to struggle at this point. But if you keep climbing, you’ll eventually hit an altitude where it’s no longer possible to climb any higher. That point is what we call the absolute ceiling.

Weight and Altitude

Weight also has a role in your optimal cruising altitude. Heavier aircraft need more lift and more thrust to climb, so they often cruise at lower altitudes early in the flight.

But what happens when you burn off fuel as you fly? Well, your aircraft gets lighter, which means it can climb further into more efficient altitude bands.

Atmospheric Conditions

Of course, you’ll also want to keep an eye on what the atmosphere is doing. Remember that as temperature increases, or as you rise in altitude, the air density decreases. That’s because air means the molecules get spread out, and there are fewer of them in a given volume.

What does this mean for performance? That thinner air results in less lift from the wings, less thrust from propellers or jets, and less power from piston engines because they ingest less oxygen.

What we’re concerned about is the density altitude. It starts with pressure altitude, takes it a step further, and then corrects it for non-standard temperature. The number you arrive at is the altitude at which the aircraft “feels” like it is operating.

When the air is hotter than ISA or the pressure is lower than standard, density altitude increases, meaning the aircraft performs as though it were at a higher altitude in thinner air.

Air Traffic Control and Airspace Structure

When you’re cruising at altitude, much of your flight path is shaped by the structure of the airspace and the role of air traffic control. Every aircraft operating in controlled airspace must receive an ATC clearance.

Once you’re on your IFR (instrument flight rules) clearance, ATC assigns your cruising altitude or flight level to ensure safe vertical and lateral separation from other traffic. The rules governing which flight levels you fly are spelled out in 14 CFR 91.179.

That regulation states that you must maintain the altitude or flight level assigned by ATC when you’re operating under IFR in controlled airspace.

There’s also the well-known directional rule for flight level assignment based on your magnetic heading:

- If your magnetic track is 0° through 179° (eastbound), you are generally assigned odd flight levels (for example, FL 310, FL 330).

- If your magnetic track is 180° through 359° (westbound), you usually fly even flight levels (for example FL 320, FL 340).

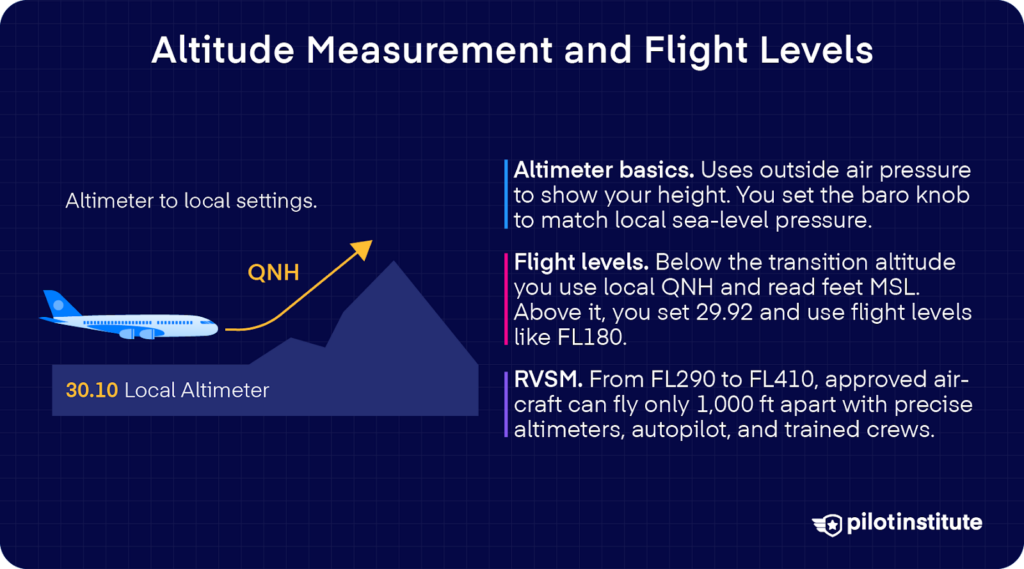

Altitude Measurement and Flight Levels

The altimeter is the only instrument in small aircraft that gives you altitude information. It works by measuring ambient static air pressure through the static port on the aircraft.

As you climb, the outside pressure drops and the internal diaphragm or bellows inside the instrument expand. That causes the needle to move to a higher reading.

But if the altimeter is based on the static air pressure, and the pressure constantly changes from one place to another, how do pilots stay on the same page?

To make sure altimeters are accurate and consistent, you can adjust the altimeter’s barometric setting (in the Kollsman window) to the current local sea-level pressure or the prescribed setting.

When to Use Flight Level?

At lower altitudes, you use the local pressure setting (often called QNH) so your altimeter reads height above mean sea level.

But above the transition altitude, you switch to the standard pressure setting of 29.92 inches of mercury (or 1013.25 hPa). That’s the point where you transition to flight level from MSL.

For example, in U.S. airspace, once you climb above 18,000 feet MSL, you set your altimeter to 29.92 and begin flying in flight levels (e.g., FL180 = 18,000 feet).

Reduced Vertical Separation Minimum (RVSM)

Airspace can get pretty crowded. Yes, even at very high altitudes.

In situations like this, the efficient use and safe separation of aircraft are handled by the Reduced Vertical Separation Minimum (RVSM). This system applies in airspace from FL 290 to FL 410 inclusive.

Under RVSM, the vertical separation between properly equipped aircraft is reduced to at least 1,000 feet. Aircraft are spaced more closely vertically, which makes for more available cruising levels and increases airspace capacity.

How can you operate in RVSM airspace? There are requirements for both your aircraft and crew.

For example, the aircraft must have two independent altitude-measurement systems, an altitude alert system, and an automatic altitude control system capable of maintaining altitude within tight tolerances.

The operator must obtain an RVSM approval. They have to ensure monitoring of altitude-keeping performance and that the pilots are trained in RVSM procedures.

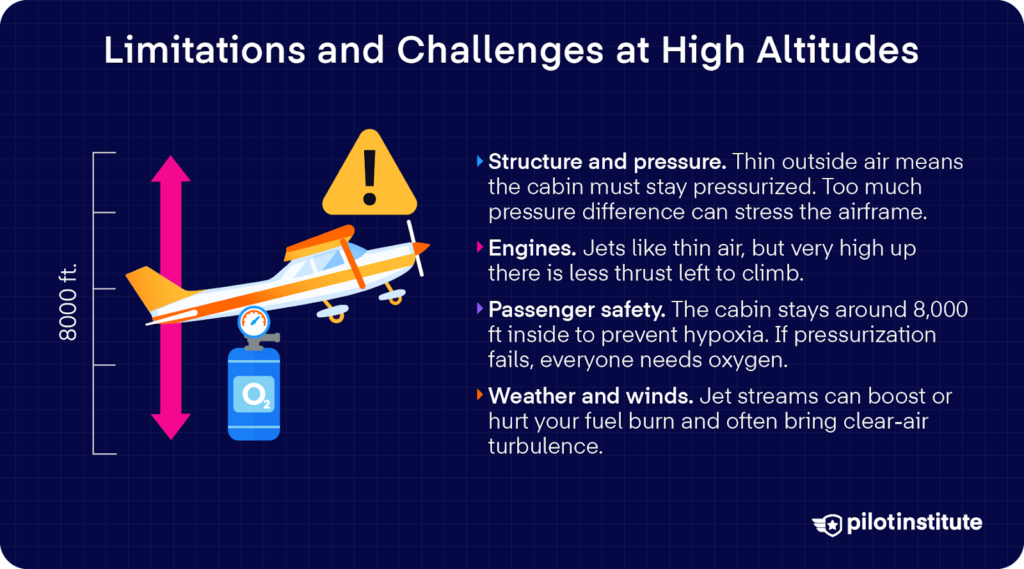

Limitations and Challenges at High Altitudes

As you climb higher in an aircraft toward its maximum capabilities, you begin to encounter structural and performance challenges that limit how high you can safely go.

Aircraft Structural and Engine Limits

The air outside thins out and pressure drops, so how does nobody suffocate at such high altitudes? Well, the cabin has to remain pressurized to keep everyone comfortable.

Differential Pressure

That growing gap between inside and outside pressure is called differential pressure. But if your aircraft’s structure can’t withstand it, the result could be a dangerous decompression or even structural failure.

To prevent that, strict limits are built into aircraft design. Under 14 CFR 25.841, pressurised cabins must be equipped to provide a cabin pressure altitude of not more than 8,000 feet under normal operating conditions.

Any airplane certified to fly above 25,000 feet must have a pressurization system capable of keeping the cabin below a pressure altitude of 15,000 feet even after a “probable failure condition.”

In other words, even if something goes wrong, passengers and crew shouldn’t be exposed to unsafe cabin pressure levels.

Engine Limitations

On the engine side, thinner air at high altitude does help reduce drag, but it also comes with a tradeoff. Jet engines rely on the mass of air flowing through them to produce thrust, and as altitude increases, the air becomes less dense.

With fewer air molecules entering the engine, there’s less oxygen for combustion and less mass flow overall, which means thrust begins to drop off.

So, even if a decrease in temperature results in more thrust, the air pressure simply falls faster than the temperature does.

This imbalance causes the engine’s overall output to decline even as the airplane climbs into smoother, more efficient air.

Passenger Safety and Comfort

Cabin pressurization is what makes high-altitude flight both possible and comfortable.

As you climb, the outside air becomes too thin to breathe safely, so the system keeps the cabin at a pressure equivalent to about 8,000 feet or lower. This protects everyone on board from hypoxia, and it’s what allows long flights without the need for oxygen masks.

But comfort is only one part of the equation. The pressurization system also controls how quickly cabin altitude changes. It prevents the kind of pressure swings that can cause ear pain or even injury.

At the same time, it constantly replaces stale air with fresh air from outside. This way, the cabin atmosphere stays clean and pleasant.

Of course, with all this automation, there’s always the risk of something going wrong. A loss of cabin pressure can happen suddenly, so you must be prepared to act fast. Quick recognition and immediate response can make all the difference.

Supplemental Oxygen

But what if the worst-case scenario does happen, like a cabin pressurization failure? Regulations in 14 CFR 121.329 require supplemental oxygen for crew when cabin pressure altitudes exceed 10,000 feet up to 12,000 feet for flights over 30 minutes.

If the cabin altitude rises above 14,000 feet, the supply must cover 30 percent of the passengers for that portion of the flight.

And at even higher levels, there’s no room for compromise. There must be enough oxygen for everyone on board for the entire time spent at those altitudes.

Environmental Factors

At high altitudes, you’ll often encounter the powerful, fast-moving air currents known as the Jet Stream. These winds can offer a big boost when you’re travelling in their direction. It can reduce your fuel burn and shorten your flight time.

For instance, one study found that transatlantic flights between London and New York could have saved up to about 16% of fuel by better aligning with favourable tailwinds.

And while we did say that there’s less turbulence high above, that doesn’t mean you’re fully off the hook. If you fly into or against strong jet stream headwinds, your fuel consumption rises, and your climb profile or cruise plan may change.

Along with these winds, you’ll run the risk of experiencing clear‑air turbulence (CAT), which often happens in the upper troposphere near jet streams where wind shear and thin air interact.

CAT can occur without visible clouds and can be hard to spot, so you always have to plan for it and stay alert.

Factors Influencing Altitude Changes During Flight

Your flight altitude is not set in stone. In fact, it can change as the flight progresses.

As fuel burns off during flight, the aircraft’s weight steadily decreases. With less weight to support, it doesn’t need as much lift to stay level.

That shift creates a few options for the pilot and the airplane’s performance. The aircraft can either climb higher, fly faster, or the engines can be throttled back to produce less thrust.

Let’s take a look at each of your options. First, when you increase speed, you also get more drag. That can raise fuel consumption.

What if you reduce thrust? That could just cause the engines to operate less efficiently.

Climbing, however, gets you to that sweet spot. When you gain altitude as your aircraft loses weight and the air thins, drag naturally decreases. That means your airplane can maintain its power setting while still improving efficiency.

ATC Coordination

The drawback? A cruise climb doesn’t always fit within air traffic procedures or busy airspace operations.

In regions like the U.S. or Europe, traffic is often so dense that allowing one aircraft to climb continuously could block others from flying at their ideal altitudes.

That only shows the importance of coordination with ATC. And alongside that, you have to constantly keep track of your aircraft’s weight and the available airspace.

When everything lines up, then you can request clearance to climb.

Conclusion

You’ve probably taken up flying to reach great heights, but that comes with understanding what makes those heights possible.

Keep asking questions and challenging yourself. In order to master how to fly, you must know why flight works the way it does.

You can climb in altitude, but more importantly, you should also climb in knowledge. That only makes you a better and more capable pilot.