-

Key Takeaways

-

What Is a Biplane?

- Quick Comparison: Biplane vs. Monoplane

-

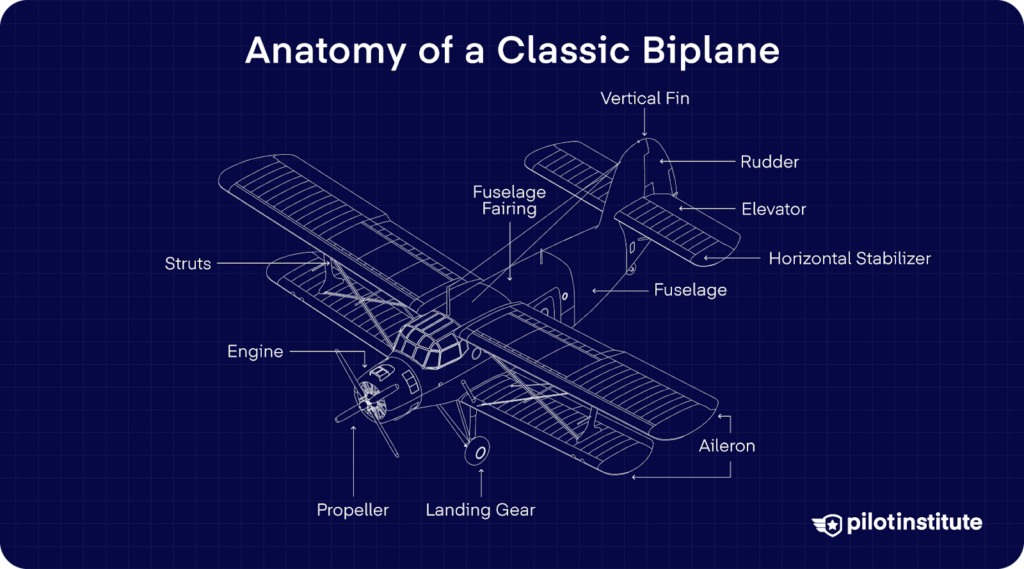

Anatomy of a Classic Biplane

- Wing Structure

- Bracing and Rigging

- Fuselage, Empennage & Landing Gear

-

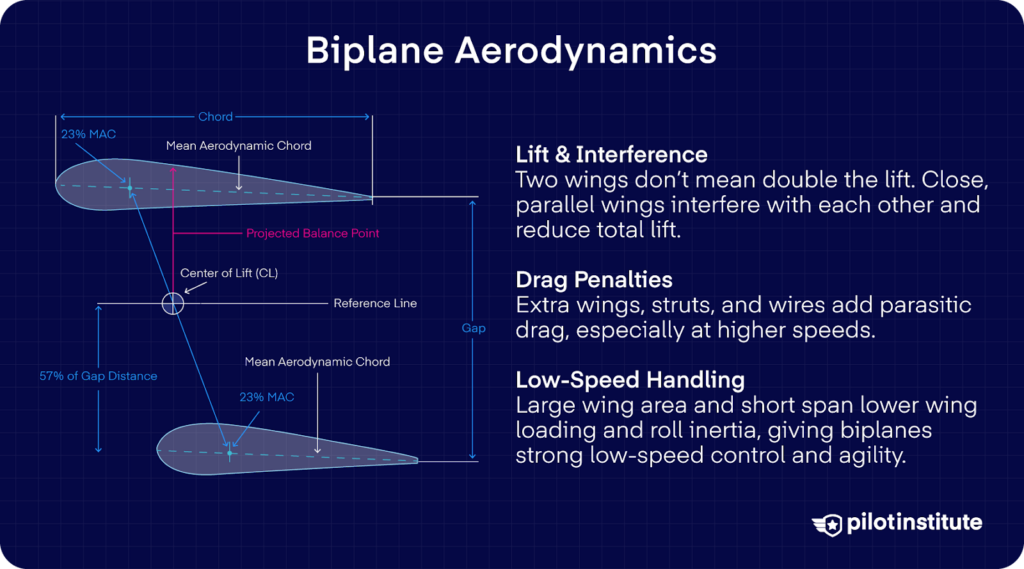

Aerodynamics in Two Layers

- Lift & Interference

- Drag Penalties

- Maneuverability Superpowers

-

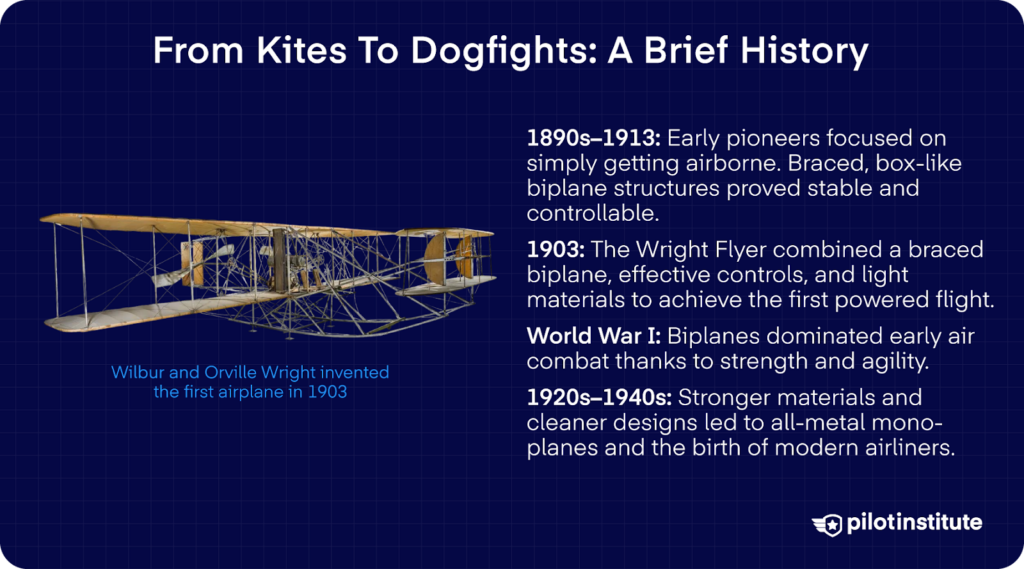

From Kites to Dogfights: A Brief History

- Pioneers (1890s–1913)

- The WWI Golden Age

- Transition to Monoplanes (1920s–1940s)

-

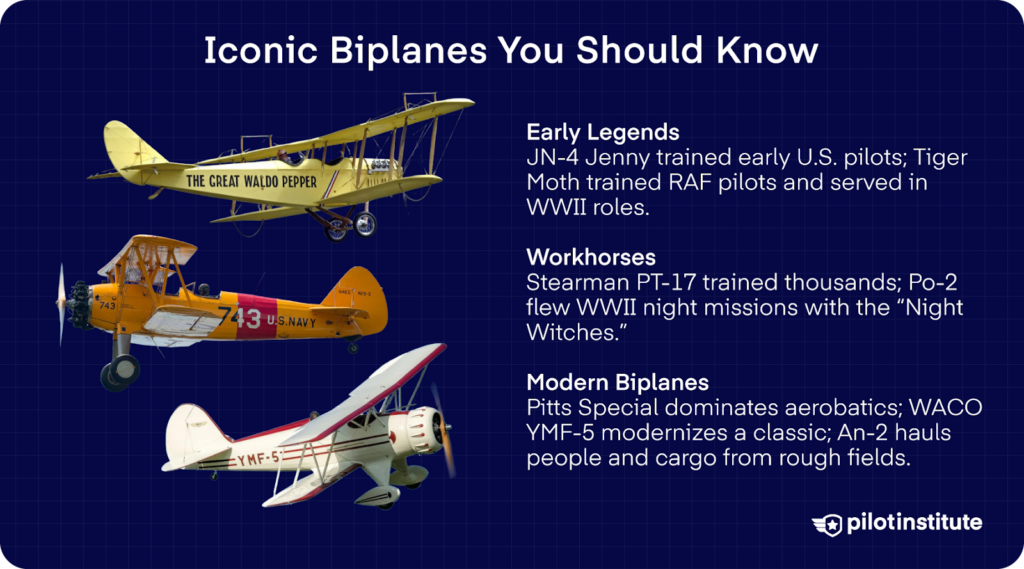

Iconic Biplanes You Should Know

- Early Legends

- Record-Setters & Workhorses

- Modern Stars

-

Flying a Biplane Today

- Handling Characteristics

- Aerobatics & Airshows

-

Where You’ll Still See (Or Use) Biplanes

- Recreational Flying & Flight Training

- Agriculture & Specialty Roles

- Experimental & Future Concepts

-

Conclusion

You slip into an open cockpit, and the world changes fast. Wing struts hum and fabric wings flex as you bank over a cornfield. All of that is celebrated in a biplane.

Two-winged airplanes once ruled the sky, so where are they now?

Let’s go all the way back, to the Wright Flyer’s first powered hop in 1903 and World War I dogfights. You’re about to learn the real origins of aviation.

Pass the FAA Private Pilot. 99% Guaranteed

Short, visual ground school that gets you ready the first time.

- 35 hours of step-by-step video lessons.

- Practice exams + large question bank.

- Free instructor endorsement.

- Lifetime access, mobile/offline + live office hours.

Key Takeaways

- Biplanes use two wings to trade speed for durability and precise low-speed control.

- Interference and bracing increase drag, which limits cruise speed.

- Tailwheel handling and rigging checks demand smooth inputs.

- Biplanes still thrive in aerobatics, recreation, utility work, and experimental research today.

What Is a Biplane?

The first and most obvious thing that distinguishes a biplane is the two main wings stacked one on top of the other. The better question would be, why two wings?

Those two wings helped the earliest aircraft get into the air with the limited technology they had at the time.

Designers in the first decades of flight didn’t yet have access to strong and lightweight materials or powerful engines. How did they work around those?

Stacking two wings lets them pack more lifting surface into a shorter span without making the structure too heavy or flimsy. And depending on the setup, you might even get a clearer view in certain directions.

Gap, Stagger, and Bay

The vertical spacing between the upper and lower wings is called the gap. It is measured from the chord line of one wing to the chord line of the other. Designers choose that spacing carefully to balance lift and drag.

You’ll also hear the word stagger. That describes how far forward or backward the top wing is relative to the lower wing.

If the top wing sits ahead of the bottom wing, that is called positive stagger. If it sits behind, that is called negative stagger.

What’s the difference? Aerodynamically, forward stagger tends to work better. You can reduce the gap without giving up efficiency.

And when both wings are producing similar lift, the forward upper wing can actually experience less drag than the lower wing.

That lowers the center of drag, which can improve stability when power is applied.

Between the pairs of struts that connect the upper and lower wings on each side of the fuselage, there’s a space called a bay.

If you see just one pair of struts and the space between them on each side, that aircraft is a single-bay biplane.

If there are two or more sets of struts creating more divisions between the wings, then it is a multi-bay design.

Quick Comparison: Biplane vs. Monoplane

So, aside from the obvious, how does a biplane differ from a monoplane?

Both monoplane and biplane wings generate lift in the same basic way. Each wing uses generally the same airfoil shape. That part doesn’t change just because you add a second wing.

Efficiency is where the difference shows up. In a biplane, the two wings sit close enough that the airflow from one interferes with the other. The struts and bracing between the wings also add drag.

But even so, two wings must mean twice the lift, right? Not quite.

Even if a biplane and a monoplane have the same wingspan, the stacked wings interfere with each other’s airflow. Add in the extra drag from struts and wires, and the overall performance gain isn’t what you’d think it should be.

All of that makes the biplane less aerodynamically efficient, especially at higher speeds. A monoplane avoids those penalties, which is why it usually cruises faster and burns less fuel for the same job.

But that doesn’t mean biplanes are worse. They shine in certain roles. Many biplanes are popular in aerobatics because they tend to roll quickly and feel responsive.

Some pilots also find them easier to control, particularly at lower speeds. Ever watched a biplane airshow routine? That agility is the payoff.

| Trait | Biplane | Monoplane | Why It Matters |

| Wing Area | High. | Lower. | Affects stall speed & climb. |

| Structural Bracing | External struts/wires. | Internal spars. | Drag vs. weight trade-off. |

| Roll Inertia | Low (short span). | Higher. | Agility vs. efficiency. |

| Cruise Speed | Limited by drag. | Higher potential. | Explains the historical shift. |

Anatomy of a Classic Biplane

Wing Structure

Now, let’s talk about the parts that make up a biplane. Starting with the wings, you can imagine their framework like a skeleton. The spines in the wing are called the spars.

Did you know that these were made of wood like spruce on many classic aircraft? The spars run from the fuselage out toward the tip and carry most of the flight loads.

Now, between the spars are ribs. Ribs give shape to the wing and help spread loads into the spars. They often are made from plywood or wood truss sections in older aircraft.

Once the spars and ribs are assembled, thin cloth fabric goes over them. This fabric is then treated with special lacquer or “dope” that protects it against moisture.

That doped fabric becomes a light but surprisingly strong covering that produces the wing’s shape while protecting the structure.

At the center of the aircraft, cabane struts connect the top wing’s center section to the fuselage. These are usually vertical or slightly angled posts strong enough to carry compression loads.

How are the two wings connected? Look outboard between the upper and lower wings, and you’ll see the interplane struts.

These struts press the wings apart. They also help transfer loads carried by one wing into the other. Under landing loads and lift loads, these struts resist the forces that can bend or twist the wings otherwise.

Bracing and Rigging

Ribs do a great job of holding the wing’s airfoil shape, but they aren’t very strong side to side. The solution? Fabric tapes.

Builders weave these tapes over and under the ribs, which helps prevent sideways bending and keeps the rib structure stable under load.

Wing strength also depends heavily on drag and antidrag wires. These wires run diagonally between the spars in a crisscross pattern. That makes a truss inside the wing.

It resists forces that act along the wing chord, especially during acceleration and gusty conditions.

Each wire has a specific job. A drag wire resists forces that try to pull the wing structure backward. An antidrag wire resists forces that push it forward.

Fuselage, Empennage & Landing Gear

All of these parts come together at the fuselage, which you can think of as your airplane’s backbone.

Early biplanes often used truss-type structures. They were tubes or beams joined in a series of triangles to resist loads.

At the rear of the fuselage, the empennage includes the vertical fin, rudder, horizontal stabilizer, and elevator.

Underneath, classic biplanes almost always use conventional landing gear, which is a staple in classic aircraft. That means two main wheels forward and a support at the tail.

Early aircraft often had a tailskid instead of a wheel. The tailskid was a simple wooden or metal skid that supported the tail and helped slow the aircraft on soft fields.

Aerodynamics in Two Layers

Lift & Interference

Remember how having two wings does not simply double the lift of a single wing? That’s because in a biplane, the airflow over one wing affects the other.

That interaction changes how much lift each wing produces. When the wings are close together and parallel, their mutual influence actually makes less lift than what each would make alone!

Drag Penalties

They also pay their price in parasitic drag. Add struts, wires, and the extra wing surfaces, and all that adds up to skin-friction drag and form drag.

Those airplane parts disturb the airflow and add resistance, especially at faster speeds.

Maneuverability Superpowers

But where a biplane really shines is in low-speed handling. Two closely spaced wings give you a large total wing area in a compact span.

Lower wing loading makes it easier to fly at lower airspeeds and gives you more lift for a given bank angle.

A shorter wingspan also means lower roll inertia, which is the resistance to starting or stopping a roll. With less inertia, the aircraft responds more quickly to your roll control inputs, so you feel agile at slow speeds.

From Kites to Dogfights: A Brief History

People in the late 1890s weren’t concerned about jets or long-haul travel. Before that, they were trying to figure out how to get off the ground in the first place. Now, let’s dive into aviation’s experimental era.

Pioneers (1890s–1913)

The Box Kite

In November 1894, Lawrence Hargrave did something that sounds reckless even by early aviation standards. He launched four box kites linked together from a beach, then climbed into a seat hanging beneath the lowest one.

A strong gust lifted him off the ground, but instead of tumbling around, the kites stayed remarkably stable. The box shape kept them steady even as the wind buffeted and shifted.

That stability turned out to be the real breakthrough. What was the lesson here? A structure braced in multiple directions could stay rigid and controllable in turbulent air.

Chanute and Herring

Not long after, other inventors took notice. One of them was American engineer Octave Chanute, who exchanged letters and ideas with Hargrave. Around the same time, he was obsessively experimenting with gliders.

In 1896, he teamed up with Augustus Herring and a small group of flying enthusiasts and headed to the windy shores of Miller Beach along Lake Michigan, near Gary, Indiana.

The group tested three different designs, including one that started life as a triplane. Early flights quickly exposed a problem.

The bottom wing kept digging into the sand during takeoff and landing. So, they made a bold change and removed the lower wing entirely.

The result surprised everyone. The modified biplane became the most successful glider of its time.

What made it work so well? The answer was structure.

Chanute’s glider used a rigid biplane framework with vertical posts and diagonal bracing, a layout known as a Pratt truss.

This arrangement created a strong, lightweight box that resisted bending and twisting in flight. The design proved so effective that it became the structural blueprint for many early aircraft.

The Wright Flyer

Those experiments inspired a pair of bicycle-shop brothers in Ohio, known as the Wright brothers. Ring any bells?

The Wright Flyer that finally flew at Kitty Hawk in December 1903 used a braced biplane structure that was both strong and flexible.

The control surfaces followed a layout that looks unusual today. A twin-surface horizontal elevator sat out front, while a twin-surface vertical rudder was mounted at the rear.

Why put the elevator ahead of the wings? The Wrights believed a forward control surface would help with pitch control and reduce the risk of a stall.

The long, straight structural members, including the wing spars, were made from spruce because it was light and strong.

The ribs and other curved or shaped parts were made of ash, which handled bending and shaping better. All of the aerodynamic surfaces were covered in tightly woven muslin cloth that created a smooth airflow while keeping weight down.

Power came from a four-cylinder gasoline engine that the Wright brothers designed themselves. After the first few seconds of operation, it produced about 12.5 horsepower.

And with the Wright Flyer came a whole approach to aircraft structure that would take over early aviation.

The WWI Golden Age

Then came the Great War in 1914, and aircraft design jumped forward faster than anyone could have guessed. Fighters like the British Sopwith Camel were built tough and stressed for combat. They had rotary engines and twin machine guns bolted to their fabric-covered frames.

The Camel became one of the most famous combat aircraft of World War I because of its agility and combat record.

There’s also the German Fokker D.VII. It was one of the standout fighter aircraft of the First World War, and it showed up in writing.

In fact, the Armistice that ended the war included a specific requirement that all Fokker D.VII aircraft be surrendered immediately.

Transition to Monoplanes (1920s–1940s)

By the 1920s and 30s, engineers had begun to prove that better materials and design could overcome the limits that once made biplanes so attractive.

The Junkers J 1 was the first aircraft built entirely of metal. It wouldn’t revolutionize combat overnight, but it showed that you could build strong, self-supporting wings without sheets of fabric and external wires.

But designers quickly learned that the strength and durability of steel came at a cost. The aircraft was heavy and sluggish to handle.

What if the structure could be just as strong without all the weight? The answer was aluminum, a material that had only recently become practical for manufacturing.

Everything quickly changed after that. Designers used aluminum to create some of the world’s first civil airliners, including the F 13 and the G 24.

Then came the Douglas DC-3. It was fast, reliable, easy to maintain, and comfortable for passengers. And today, hundreds of DC-3s are still flying.

Iconic Biplanes You Should Know

Early Legends

The Curtiss JN-4 Jenny is closely tied to the barnstorming era of aviation. It’s also the airplane that taught a generation of American pilots how to fly.

From roughly 1916 to 1925, if someone learned to fly in the United States, there’s a good chance they did it in a Jenny. Why that aircraft? It was forgiving and well-suited to training new pilots from the ground up.

Across the Atlantic, the Royal Air Force used the de Havilland DH.82 Tiger Moth extensively. It’s best known as a primary trainer. For many pilots, this was the first aircraft they ever flew.

Its job didn’t stop at training, though.

During the Second World War, RAF Tiger Moths were pressed into other roles. Some flew maritime surveillance missions. Others were assigned to defensive anti-invasion duties.

In certain cases, aircraft were even modified to act as lightly armed bombers. Many Tiger Moths later went into civilian use, and you still see them flying at vintage clubs today.

Record-Setters & Workhorses

The Boeing-Stearman PT-17 is one of those workhorses people instantly recognize. Thousands were built to train military pilots in the 1930s and 1940s. And after the war, many found second lives as crop dusters and stunt aircraft.

If you want sheer numbers, just look at the Polikarpov Po-2. The biplane was built in huge quantities as a trainer and utility aircraft.

You’ve probably heard about the “Night Witches.” If this is your first time hearing about it, they were an all-female 588th Night Bomber Regiment in World War II. They flew this humble biplane on night raids against German forces.

Modern Stars

Where are these historic biplanes today? You’ll see a couple in airshows and sport flying.

The Pitts Special family is one of the most famous modern aerobatic biplanes. The design has evolved since the 1940s, but it remains a staple for aerobatic pilots and sport flyers.

The WACO YMF-5F is another modern classic. These are new-built biplanes that capture the look and feel of 1930s designs, but with updated materials and systems.

The Antonov An-2 is a biplane designed for utility work. What can it do? It carries a dozen people or cargo and operates from rough fields.

Flying a Biplane Today

Handling Characteristics

Flying a biplane feels direct and responsive. You use the elevator for pitch control and the rudder for yaw control, coordinating them with the ailerons for smooth turns, just like in any other airplane.

In aircraft with a tailwheel, you’ll find that controlling direction on the ground and during takeoff is different from tricycle-gear airplanes because the main gear is ahead of the center of gravity.

Tailwheel airplanes require you to keep the tail straight with rudder pressure as speed changes because the aircraft can pivot more easily on the ground without natural stability from a nosewheel.

So, is it hard to fly a biplane? Not at all! But their handling characteristics reward smooth and coordinated control inputs.

Aerobatics & Airshows

Many biplanes still have a strong following in aerobatic flying and airshows, and it’s easy to see why. Large wing area and crisp control response let these aircraft fly tight loops, quick rolls, and other classic maneuvers.

Ever notice how compact those figures look in the sky? That’s the biplane doing what it does best, as long as it’s flown within its design limits.

And as with everything else in flying, safety comes first. Pilots use proper safety restraints and follow approved procedures to manage those higher forces.

Where You’ll Still See (Or Use) Biplanes

Recreational Flying & Flight Training

You’ll still spot biplanes in the skies at small airports and vintage events where pilots love the open-cockpit experience and classic handling. Many people keep flying these aircraft because, well, they’re fun and beautiful!

Some newer companies even build brand-new biplanes. Since 1991, WACO Classic Aircraft Corporation has been producing Waco YMF models under the original type certificate and has sold more than 150.

Agriculture & Specialty Roles

Biplanes were long prized in agricultural aviation. In the early days of crop-dusting, pilots took surplus military biplanes and adapted them to spread chemicals over crops.

The Antonov An-2 still serves in agriculture and other specialty roles around the world. It was designed as a rugged utility aircraft after World War II, but now it’s being used everywhere. Crop spraying, freight, forestry work, and more!

Experimental & Future Concepts

Biplanes haven’t completely disappeared, even in advanced aerospace research. What are engineers and scientists up to these days?

Well, they’ve long studied how two wings interact at supersonic speeds. One of the biggest goals is to find ways to reduce sonic boom and drag.

Studies of the Busemann biplane show that two-element wing setups might be able to reduce shock waves at designed supersonic conditions.

On the lighter side of experimental flying, builders would create scaled or carbon-fiber-modernized replicas of classic biplanes.

For example, the Samson Mite is a 75% scale replica inspired by a classic aerobatic biplane. It’s built with a modern radial engine and contemporary materials to keep the classic lines alive in a lighter, fun aircraft.

Conclusion

Biplanes may look old-fashioned, but they are anything but obsolete.

You’ve seen how their stacked wings shaped aviation history and why they remain relevant today.

Flying one connects you directly to the fundamentals of lift and drag in a way few other aircraft can.

From the ramp or strap into an open cockpit yourself, biplanes remind you that aviation progress did not vanish into the past, but defined it. And maybe, even the future.