-

Key Takeaways

-

Understanding Power-off Stalls

- What Is a Power-off Stall?

- Why Practice Power-off Stalls?

-

How to Perform a Power-off Stall

- Setting Up

- Initiating a Power-off Stall

-

Steps for Recovering From a Power-off Stall

- 1. Pitch and Power

- 2. Maintain Control and Increase Airspeed

-

Use of Flaps During Recovery

-

Altitude Loss Considerations

-

Differences Between Power-on and Power-off Stalls

- Power Setting

- Configuration

- Recovery

-

Conclusion

If you’re coming in for a landing, the last thing you want is to face a power-off stall.

A power-off stall can happen when your engine is idle, and the aircraft slows down too much. This can cause you to lose lift. That’s why learning the recovery process is so important, especially if you’re flying at a low altitude.

Without a quick reaction, it can lead to a dangerous situation. In this easy guide, we will walk through the steps to get out of a power-off stall.

So when you’re in the cockpit, you’ll know exactly what to do.

Key Takeaways

- Power-off stalls mimic a stall during the flight’s approach and landing phase.

- Learn to identify the signs of an impending stall, such as the stall warning horn and buffet.

- Focus on reducing the angle of attack and adding maximum power simultaneously during recovery.

- Recover with a minimal loss in altitude.

Understanding Power-off Stalls

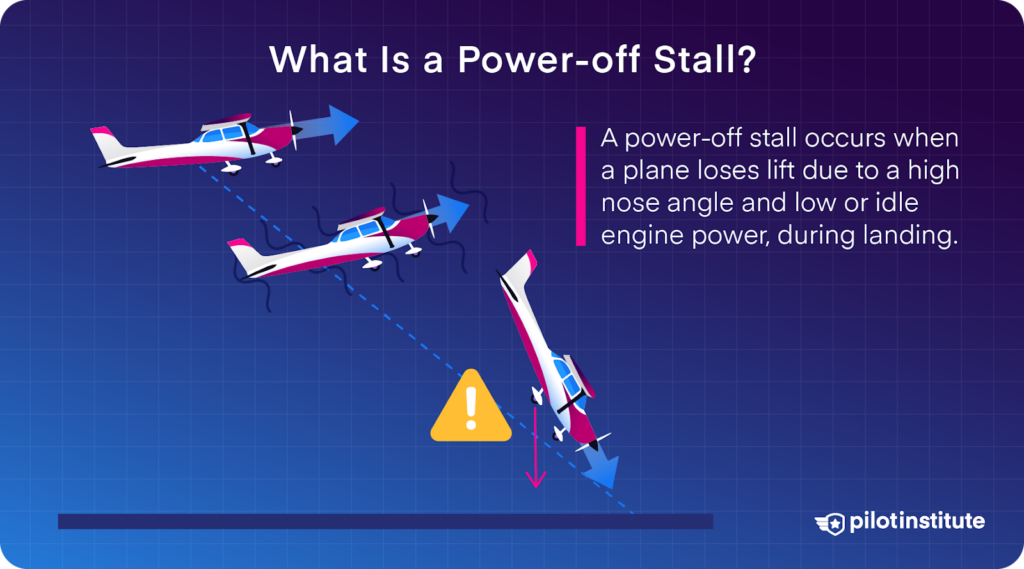

What Is a Power-off Stall?

A power-off stall maneuver emulates a stall when an aircraft is in the landing phase of the flight. As a result, these stalls are performed without power and in a landing configuration.

An aircraft stalls when the wing’s angle of attack (AOA) exceeds its critical angle. As the AOA increases, the center of pressure moves forward. This disrupts the pressure differential between the upper and lower sides of the wing. Remember Bernoulli’s Theorem and how lift is created.

The lack of a pressure differential at higher AOAs causes the boundary layer to detach from the wing. The loss of lift causes the aircraft to stall and lose altitude.

Why Practice Power-off Stalls?

When the aircraft is in a high-drag configuration, a stall at a low altitude can be quite dangerous. Especially if you aren’t anticipating it and can’t identify the tell-tale signs of an impending stall. If the aircraft stalls and you are surprised, you might not be able to recover in time.

A typical training aircraft can lose as much as 300 feet if immediate action isn’t taken to recover correctly from a stall. Why should this matter to you? On final approach, it can be the difference between recovering and crashing.

We practice power-off stalls to help us identify the signs of a stall and the characteristics of your airplane when it stalls. Most importantly, you must learn to quickly and efficiently recover from a stall.

How to Perform a Power-off Stall

The FAA’s Private Pilot Airman Certification Standards (ACS) outline the procedure for performing a power-off stall. Here’s how to do it in a training aircraft like a Cessna 172, but we’ll keep things simple and to the point.

Setting Up

Before starting any maneuver, you need a good setup. Why? Because showing sound judgment and preparation is part of what makes a good pilot.

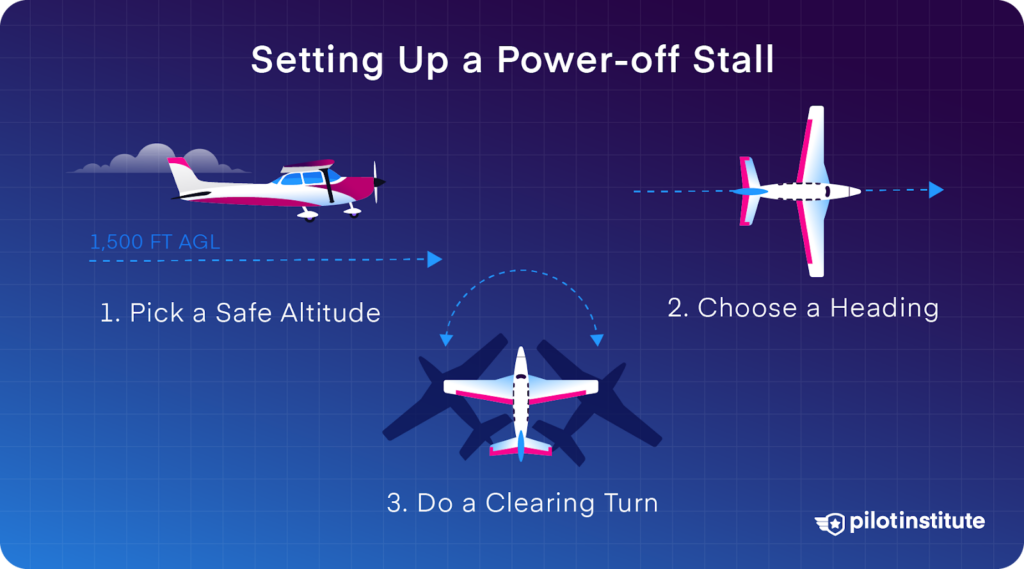

Here’s how to prepare for a power-off stall:

- Pick a Safe Altitude

- Choose a Heading

- Do a Clearing Turn

1. Pick a Safe Altitude

First, you should select an appropriate altitude that allows you to recover safely.

The ACS states that recovery should be completed no lower than 1,500 ft AGL for single-engine aircraft and 3,000 ft AGL for multi-engine aircraft.

When picking an area to practice power-off stalls, pick an area that is not close to obstacles and away from populated settlements.

If there is an obstacle in the area, choose somewhere else. If you cannot, you should add the above altitude value to the obstacle’s height.

2. Choose a Heading

Second, you should pick a heading to maintain throughout the maneuver.

The ACS requires that you maintain +/- 10 degrees in straight flight and +/- 20 degrees of bank during the maneuver and recovery. For the best performance, fly into the wind.

3. Do a Clearing Turn

Finally, before performing any maneuver, ensure that you execute clearing turns. Perform one 180-degree or two 90-degree turns to scan for traffic. Once it’s clear, you’re good to go.

Initiating a Power-off Stall

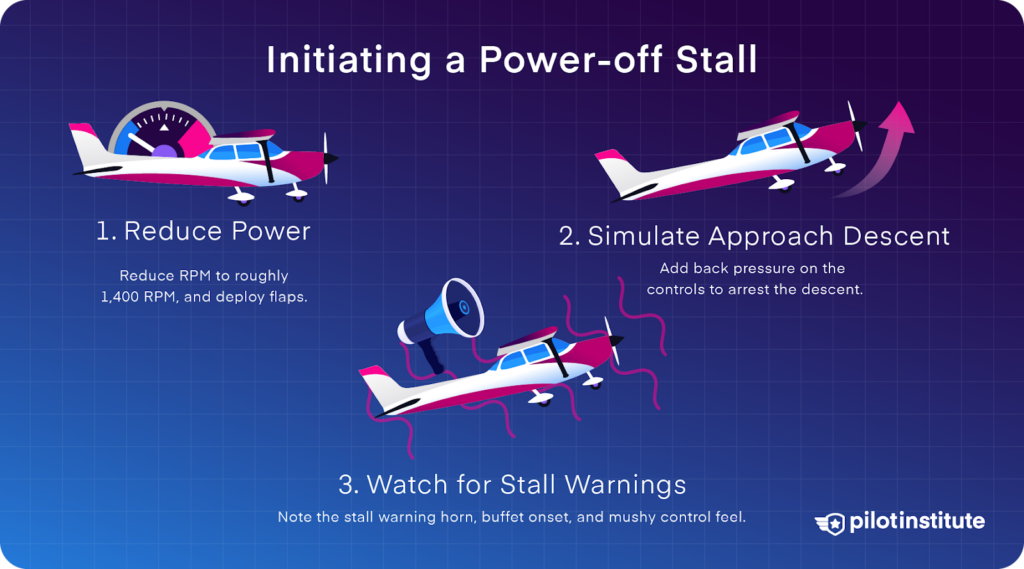

Now, let’s dive into the stall:

- Reduce Power

- Simulate Approach Descent

- Watch for Stall Warnings

1. Reduce Power

Reduce RPM to roughly 1,400 RPM and bleed off speed while maintaining altitude. Once you’re below Vfe, deploy the maximum flaps. It’s okay to do so as long as you’re within the aircraft’s limitations.

Now that the aircraft is in landing configuration, reduce your power to idle and pitch down to simulate an approach descent. As mentioned, a power-off stall emulates an inadvertent stall during a landing.

2. Simulate Approach Descent

Once you lose 100 to 150 feet, begin to add back pressure on the controls to arrest the descent. It is important to keep the aircraft level and prevent any banking with adequate control inputs.

3. Watch for Stall Warnings

When the aircraft approaches the stall envelope, make note of the signs of an impending stall. These include the stall warning horn, buffet onset, and mushy control feel. Why? Because identifying an impending stall will help you avoid one.

Gradually increase back pressure until the aircraft stalls. Once the nose drops, prepare for recovery.

Steps for Recovering From a Power-off Stall

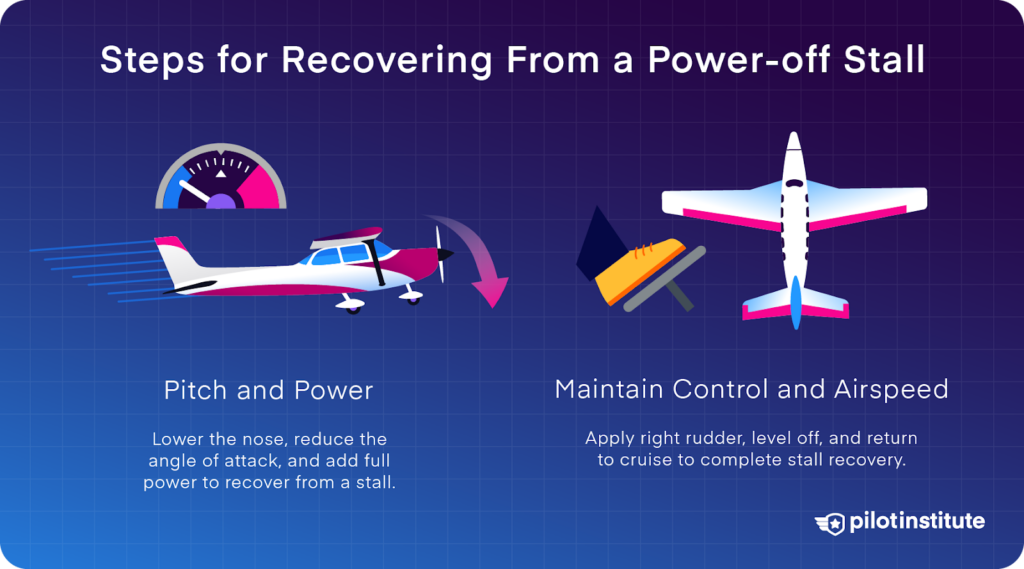

1. Pitch and Power

The first and foremost action in the recovery process is to reduce the AOA below the wing’s critical angle and get the aircraft flying again.

Once the aircraft stalls, the nose will drop; use this as an indication to reduce back pressure. Aim for a pitch attitude that points the nose just below the horizon.

Simultaneously, add full power. The quick and smooth application of power after a stall will help reduce the loss of altitude during the recovery procedure.

2. Maintain Control and Increase Airspeed

It’s important that you add right rudder to neutralize the aircraft’s left-turning tendencies. If you do not, you’ll exceed the +/- 10 degrees of heading standard outlined by the ACS.

At this point, you’ll be slightly nose down with full power, and the airspeed will climb above Vs. It’s important to arrest the descent and immediately get to a level flight attitude.

You’ve recovered from the stall after being at a level flight attitude. However, the maneuver isn’t complete until we have cleaned up and returned to a cruise configuration.

Use of Flaps During Recovery

Once you arrest the descent and recover from the stall, you need to clean up. Why is it important to return to a clean configuration? It’s mainly to increase climb performance. It’s also considered part of the stall recovery procedure.

For an aircraft like the C172, which has three levels of flaps, the use of flaps during recovery is as follows.

The final notch of flaps should be removed immediately upon arresting the descent and getting the aircraft to a level pitch attitude. Landing flaps add a lot of drag; removing this notch will help the aircraft accelerate quickly.

Now, establish a climb and aim for either Vx or Vy to return to your starting altitude (Vy is preferred as it is higher). This emulates a go-around that you must initiate if you inadvertently stall on an approach to landing.

Remove the second notch of the flaps as soon as the vertical speed indicator (VSI) shows a positive rate of climb.

Finally, remove the first notch of flaps after reaching your desired climb-out speed. Adjust the throttle and mixture to cruise settings once the aircraft is in a clean configuration.

Altitude Loss Considerations

As mentioned, an aircraft can lose considerable altitude in a stall if left untreated. As the pilot in command, it is your job to minimize the loss of altitude and recovery as soon as practicable.

Practicing stalls helps us understand why they happen, how to identify them, and how to recover from them efficiently.

It can be argued that the most important aspect of practicing a power-off stall is learning to identify it. Because if you can identify an impending stall and prevent it, you’ve already succeeded.

If you can’t prevent it, identifying an impending stall can help you prepare to recover from one. Being caught unawares will certainly result in a large loss of altitude.

The other aspect is initiating the recovery process. As soon as the nose drops, you should focus on reducing the AOA and adding maximum power. They should happen quickly and simultaneously. The result will be a descent and a loss in altitude while airspeed increases.

Once the airspeed is above Vso, you can safely regain straight and level flight. This method ensures a minimal loss in altitude during a power-off stall.

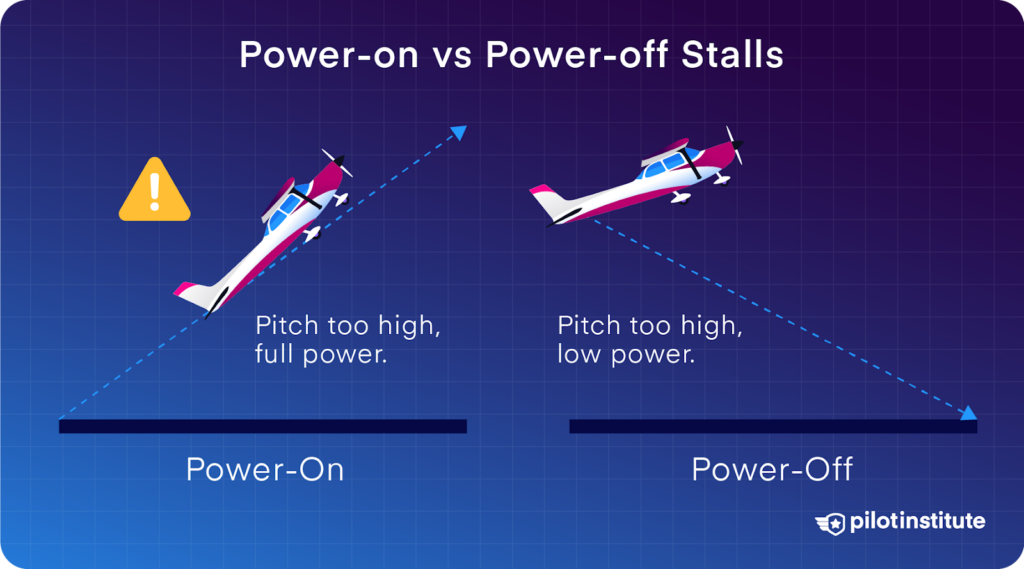

Differences Between Power-on and Power-off Stalls

Why should you know the difference between these two stalls?

The recovery procedures are different, as well as the aircraft’s performance and configuration. We should understand them both to differentiate and recover from both these stalls.

Power Setting

The power setting is the main difference between a power-off and a power-on stall.

As the name suggests, power-on stalls occur when the aircraft has at least 65% power (according to the ACS). In comparison, during a power-off stall, the power will be idle.

A high power setting means that the aircraft will stall at a much higher angle of attack. It’s mainly due to the effects of thrust and the high-energy slipstream from the propeller preventing boundary separation.

Configuration

Power-on stalls and power-off stalls are used to practice inadvertent stalls and recoveries in different phases of flight. A power-on stall represents a stall during the takeoff, climb-out, and go-around phases of flight. Meanwhile, the power-off stall represents a stall during the approach and landing phases.

As a result, the aircraft’s configuration will be different. During a power-off stall, you will have full flaps and gear-down (if the aircraft has retractable gear). You’ll often have no flaps or takeoff flaps in a power-on stall.

Recovery

Since the aircraft’s configuration is different, the recovery process will differ. One of the main differences is the act of pitching down. You don’t necessarily have to pitch below a level-flight attitude in a power-on stall.

But in a power-off stall, you have to pitch down to allow the airspeed to increase and stabilize the aircraft. Furthermore, you have to arrest this descent as soon as possible to reduce the loss of altitude.

Finally, the process of cleaning up adds a lot of extra steps to the recovery of a power-off stall that doesn’t exist in a power-on stall.

Conclusion

Power-off stall recovery isn’t something you want to figure out in the moment. You’ve got to be ready to lower the nose, apply power, and bring those flaps in at the right time.

And while practice makes perfect, knowing these steps by heart will make sure you’re prepared for anything.