-

Key Takeaways

-

1. Who This Is For

-

2. Certificates in Order: What the FARs Actually Allow

- Minimums At a Glance

- The 50 NM / Night Limitation

-

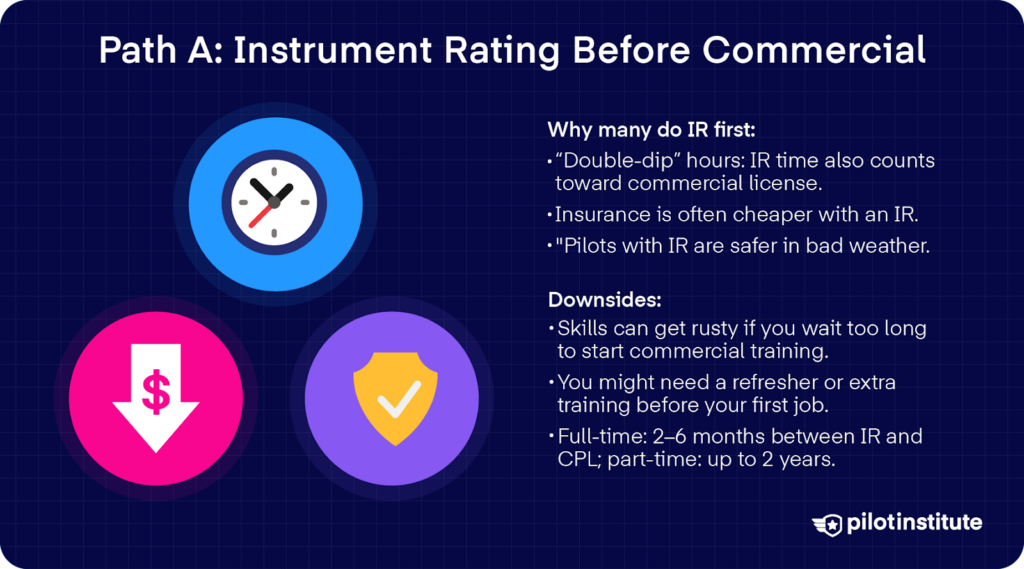

3. Path A: Instrument Rating Before Commercial

- Pros: Why Many Schools Push IR First

- Cons: When IR First Hurts

-

4. Path B: Commercial First, Instrument Later

- Pros: Work Right Away

- Cons: The Fine Print

-

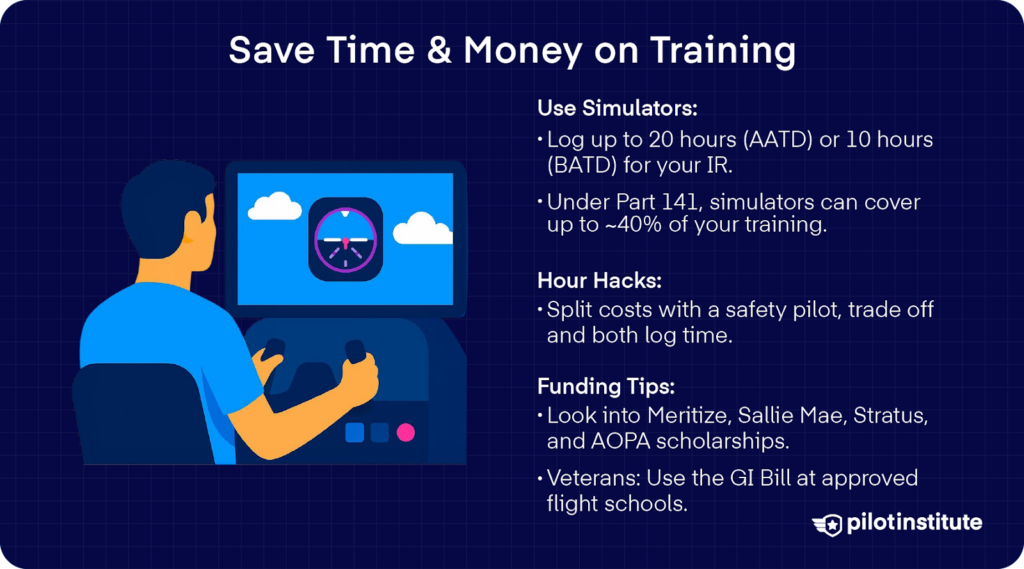

5. Save Time & Money on Training

- Leverage Simulators (BATD/AATD)

- Smart Hour-Building

- Financing, Scholarships, GI Bill

-

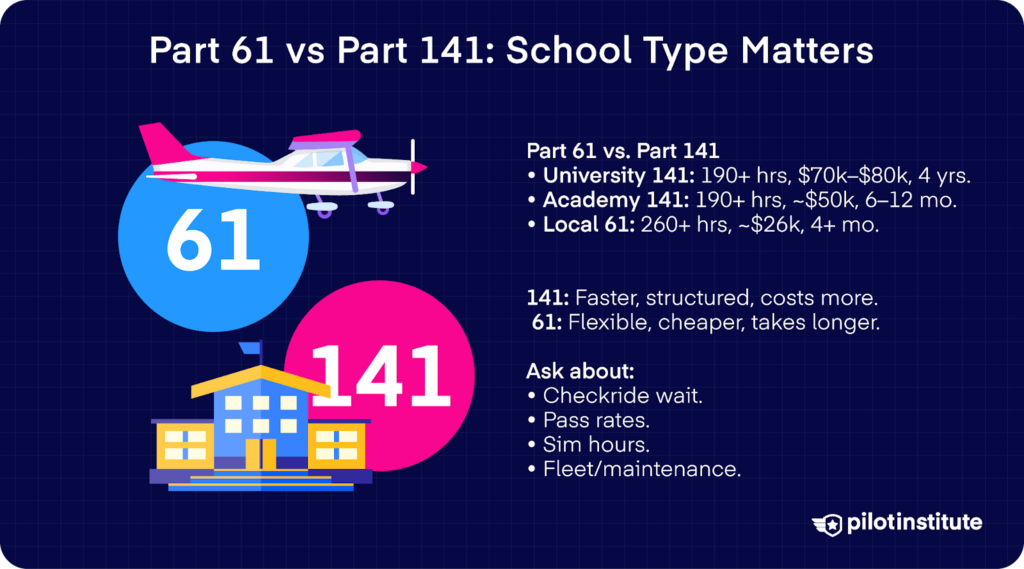

6. Part 61 vs Part 141: School Type Matters

- University vs Local FBO Cost/Time Table

- Questions to Ask Before Signing

-

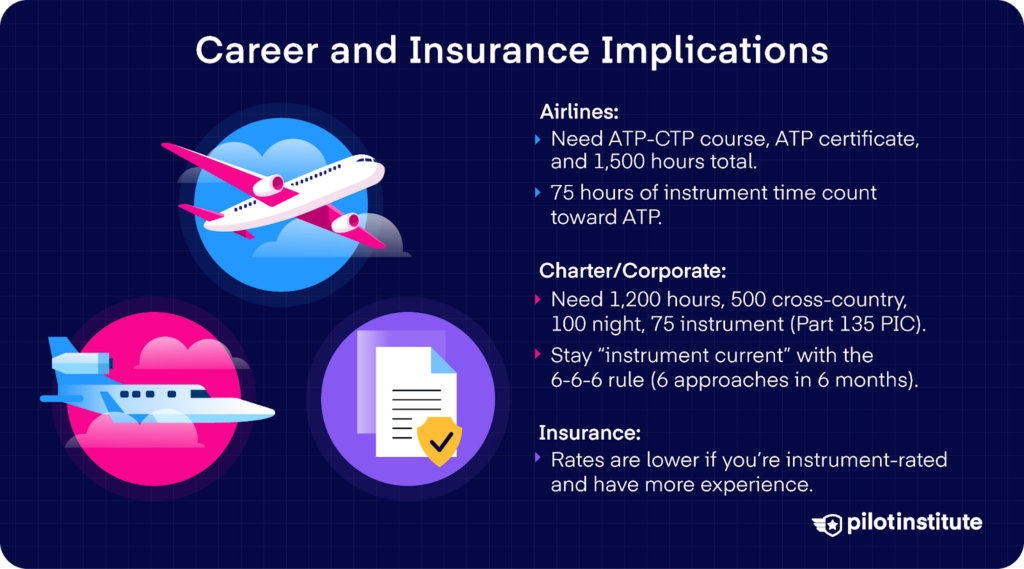

7. Career and Insurance Implications

- Regional Airline Timeline

- Corporate & Part 135 Reality Check

- Insurance Matrix

-

8. Decision Matrix: Choose Your Best Path

-

9. Common Questions

- “I can legally haul freight VFR at night without IR.”

- “Will my CPL training get delayed if I fail the IR knowledge test?”

-

Conclusion

You’re at 110 hours staring at two syllabus binders. You’ve got one for Instrument Rating and another for Commercial Pilot License, and you can only do one program at a time.

The cost of flying continues to rise, and DPE schedules are backed up for weeks. The wrong sequence could cost you precious time and money. Which order is lighter on the wallet and opens doors faster?

Let’s look at the numbers and map out the maze of regulations. You’ll see precisely how each path affects your budget, your timeline, and your first flying job.

Key Takeaways

- Doing your IR first improves safety, lowers insurance premiums, and meets most Part 135 hiring minimums sooner.

- The downsides are the higher upfront cost and the risk of losing IFR proficiency.

- Starting with your commercial pilot training helps refine your VFR flying skills and allows you to start earning early.

- The drawback is limited job eligibility due to non-IR restrictions and higher insurance premiums.

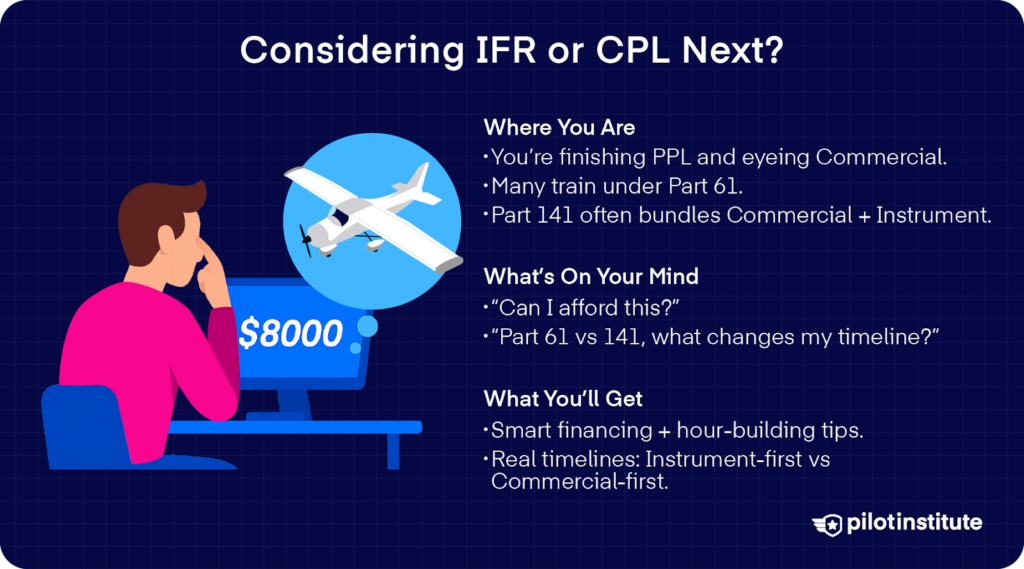

1. Who This Is For

You’re probably deep in your private pilot journey already. Maybe you’re a late-stage PPL holder thinking about building toward a commercial certificate.

Most likely, you’re training under Part 61, not Part 141. That’s because under Part 141, the rules generally require you to already hold an instrument rating (IR) or train for it together with your commercial training.

Perhaps you’re looking into colleges, switching careers, or eyeing aviation as the next big move. You’re wrestling with doubts. You wonder whether you can afford all this (budget anxiety is real).

You may feel confused by the regulations, particularly the differences between Part 61 and Part 141 requirements. You’re probably wondering, “How will the rules affect my budget and timeline?”

Let’s talk about your financing options and smart strategies to build your hours. We’ll look at a realistic timeline if you choose to start with either instrument or commercial.

2. Certificates in Order: What the FARs Actually Allow

Minimums At a Glance

| Certificate (Part 61) | FAA Reg. | Total Hours | IFR | Cross-Country | Typical Cost | Written / Practical Fees |

| Instrument (IR) | §61.65 | 40 IFR (15 dual) | Holds, approaches, | 250 NM IFR | US$10k to US$15k | $175 / $600 |

| Commercial (CPL-SEL) | §61.129 | 250 TT | 10 hours | 300 NM VFR | US$3k to US$50k | $175 / $800 |

Okay, first things first. What does the FAA require for your instrument rating and commercial certificate under Part 61?

Instrument Rating Requirements

To qualify for an instrument-airplane rating, you’ll need at least 50 hours of cross-country time as pilot in command, and at least 10 of those hours must be in an airplane.

On top of that, you’ll need 40 hours of actual or simulated instrument time. And out of those, 15 hours must be spent training with a qualified instructor who holds an instrument-airplane rating.

You’ll also need to complete instrument cross-country training, which includes one IFR (Instrument Flight Rules) cross-country flight of at least 250 nautical miles (NM).

But what if you’re doing your private pilot and IR training at the same time? The great thing about that is the flexibility. You can credit up to 45 hours of cross-country time performed as PIC with an instructor toward the 50-hour requirement.

Commercial Pilot Certificate Requirements

Now, let’s talk about how you can earn a commercial pilot certificate with a single-engine airplane rating.

What will your flight training consist of? At its core, you need a minimum of 250 total flight hours. This total is broken down into specific categories to make sure you’re a well-rounded professional.

The FAA also requires 20 hours of structured training in specific areas. Just some of these include (but are not limited to) 10 hours of instrument training. At least 5 of these hours must be in a single-engine airplane.

On top of training, you’ll need 10 hours of solo flight time (or supervised PIC time with an instructor). These solo requirements include a 300-nautical-mile cross-country flight with landings at three airports.

The 50 NM / Night Limitation

When you earn a commercial pilot certificate without an instrument rating in the same category and class, the FAA adds a major limitation to your privileges.

Your certificate will state that you cannot carry passengers for hire on cross-country flights beyond 50 nautical miles, and you also cannot carry them at night.

In practical terms, your commercial certificate is quite restricted until you complete instrument training.

3. Path A: Instrument Rating Before Commercial

That’s why many pilots choose to do their instrument rating first. But does it really hold up under a closer look? And will that help you stay aligned with your goals? Let’s dive in.

Pros: Why Many Schools Push IR First

One of the biggest reasons flight schools push doing the instrument rating first is that you “double-dip” your time. Every minute you spend flying under instrument conditions counts toward your 250 total time requirement for commercial pilot license.

That means you reduce the amount of pure “extra” dual time you’d otherwise need once you shift to CPL work.

Then, there’s the insurance benefit. Instrument rating is frequently cited as one of the additional ratings or certifications that providers consider when weighing risk. You’ll be seen as less of a risk with an IR, and what does that mean for you? Lower premiums!

But are you really safer with an instrument rating? You only have to look at the data to know the answer.

The NTSB found that pilots who do not hold an instrument rating are 4.8 times more likely to be involved in a weather-related accident than instrument-rated pilots.

Pilots flying Visual Flight Rules (VFR) with an instrument rating are also less likely to have fatal accidents if they unexpectedly enter Instrument Meteorological Conditions (IMC).

Cons: When IR First Hurts

But of course, this option still comes with its downsides that you need to consider.

If too much time passes after you do IR and before you begin commercial pilot training, you risk losing some of your proficiency. Skills fade, especially instrument maneuvers.

Commercial pilot training takes a while, especially when you’re just starting from the minimum hours after your private pilot and IR training.

How long does it take between completing your IR and earning your commercial certificate? There are many variables, but it could take anywhere from 2 to 6 months if you train full-time, and 1 to 2 years if you’re part-time.

That’s ages in terms of instrument proficiency. When you move toward a job, you might need an Instrument Proficiency Check (IPC) just to shake off rust.

4. Path B: Commercial First, Instrument Later

Pros: Work Right Away

Is working right away a priority? If so, then it could make sense to do your commercial training first.

Once you get that certificate, you can push on toward earning more hours quickly. You can tow banners, haul skydivers, or ferry agricultural loads, all under VFR.

You’ll get early exposure to real mission flying, even before you add IFR privileges.

Because you’re flying mostly visually to begin with, your stick-and-rudder skills tend to sharpen. You build confidence handling the aircraft in traffic and cross-country VFR navigation.

When cash flow is tight, spreading out costs can really ease the financial load. And since you’d be able to earn after getting certified, you’d have a means to support your IR training.

Still, our advice is to save up for the full cost of your instrument training before you begin, so money never gets in the way of your progress.

Cons: The Fine Print

The path isn’t free of pitfalls, though. Remember that 50 NM/night limitation? You’d be barred from carrying paying passengers on cross-country flights beyond 50 NM or at night until you get your IR.

That limitation could become a fence on your earning potential. Some charter, freight, or passenger jobs will simply be off the table until you get rated.

Thinking of moving up to a twin or a pressurized airplane? Don’t expect insurers to say yes unless you’ve got an instrument rating.

As another drawback, your radio and navigation skills may atrophy during your commercial work. Later, when you finally pursue instrument training, you may have to relearn aspects and spend extra time to rebuild proficiency.

5. Save Time & Money on Training

Leverage Simulators (BATD/AATD)

One of the smartest tools in your kit is the use of FAA-approved simulators. How can you make the most of them?

- Part 61 students can log up to 20 hours of instrument time in an AATD (Advanced Aviation Training Device) or 10 hours in a BATD (Basic Aviation Training Device) toward their IR requirements.

- For Part 141 courses, the rules are a bit different. You can only credit up to ~50% of your total flight training hours in a full flight simulator.

If you’re using a flight training device or an AATD, it’s only up to ~40%. And only 25% can be credited if it’s a BATD.

If you’re combining different types of devices, you still can’t exceed 50% overall, and each device type still has its individual cap.

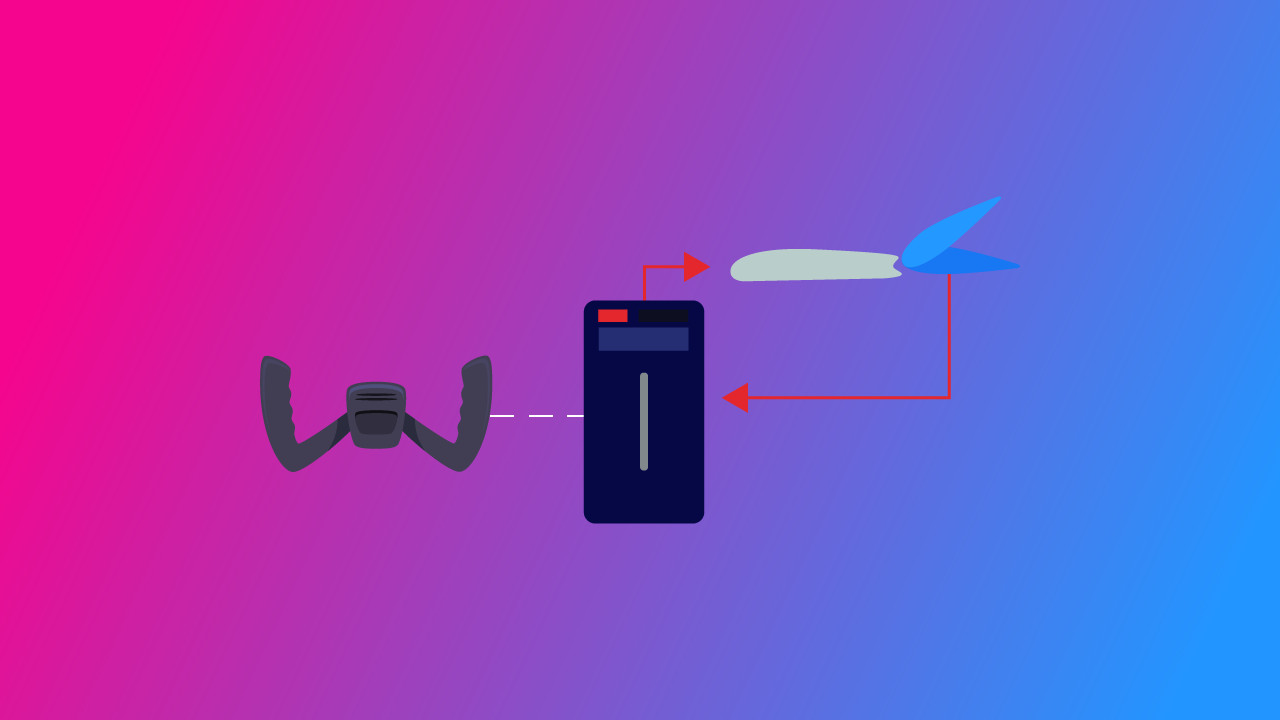

Smart Hour-Building

What other steps can you take to save money? When it’s time to get in an actual cockpit, you don’t even have to pay full price every session! One of the cleverest strategies is the safety-pilot swap.

You can fly under a view-limiting device while another instrument-rated pilot acts as safety pilot. Those hours can count toward both pilot-in-command time and simulated instrument time.

Once you swap, those hours will count towards your total flight time. And remember, you’re paying half price the whole time!

Financing, Scholarships, GI Bill

Some financing options in the U.S. market include Meritize, Sallie Mae, and Stratus. AOPA’s “You Can Fly” scholarships are worth chasing as long as you meet their requirements.

If you’re a veteran, there’s good news!

As long as you meet the requirements, you can use your benefits to fund your flight training through the GI Bill. Just take note that you must be enrolled in a Part 141 or Part 142 school approved by the FAA.

6. Part 61 vs Part 141: School Type Matters

It’s time to make a choice: Part 61 or Part 141? Every pilot eventually faces this decision, and it can shape how fast you train and how much you’ll spend along the way.

University vs Local FBO Cost/Time Table

| Program Type | Total Hours to IR + CPL | Est. Tuition | Typical Duration | Extras |

| Univ. Part 141 | 190+ | US$70k to 80k | ~4 years | Lab fees, dorms. |

| Academy Part 141 | 190+ | ~US$50k | 6 to 12 months. | Housing blocks. |

| Local FBO Part 61 | 260+ | ~US$26k | 4 months or more. | Pay-as-you-go. |

University Part 141

In a university/college Part 141 integrated program, you’ll typically find a curriculum that bundles private pilot, IR, and commercial pilot training under a single structure of about 190 hours. Some even include a multi-engine rating and flight instructor certification.

Each stage of your flight training can be counted as a course in the curriculum. In the end, you’ll earn both a college degree and FAA certification!

Because everything is packaged, tuition is quoted as a lump sum. You can expect to spend around US$70,000 to US$80,000. And since it’s part of a college degree, they tend to take around four years.

Academy Part 141

The total hours are the same in a flight training institution under Part 141. But since the programs are just for your certificates, they tend to be more affordable.

Training usually covers private and commercial certifications, as well as instrument and multi-engine ratings. You could take somewhere between 6 and 12 months to finish, and spend around US$50,000.

Local FBO Part 61

Now, at a local FBO under Part 61 training, you’ll need more hours because you’re meeting the full regulatory minima (or above). You may log 250 hours or more, combining IR and commercial hours.

But even so, you may be paying less per hour. To illustrate, the total cost for commercial pilot training could be just US$20,000, and your instrument rating can cost around US$6,000. The timeline is also much more flexible, so you can finish training for both as quickly as four months!

Questions to Ask Before Signing

Treat your decision process like you’re making a major purchase. You want to be sure about which school you’ll spend your time and money on, which means you’ll need to ask questions.

Ask about DPE/examiner availability. If checkride slots are months away, you could be parked waiting. What’s the percentage of their students who pass the knowledge and practical tests on the first try?

Make sure to ask what kind of simulators they have (BATD/AATD), so you know how many simulator hours you can credit.

Ask about fleet and maintenance downtime. What’s their fleet size? What’s the average age of their aircraft? How often are they grounded for maintenance?

You could also inquire at your local FSDO (Flight Standards District Office), which keeps files on all flight schools in your area. They maintain oversight records and certification status. Contacting them helps a lot to get an official check on your options.

7. Career and Insurance Implications

Regional Airline Timeline

You’ll eventually hit two big milestones if your eyes are set on the airlines: the ATP-CTP (Airline Transport Pilot – Certification Training Program) and the famous 1,500-hour rule.

You’ll need an ATP certificate to command scheduled airline operations. But before you can even take the ATP checkride, completing an ATP-CTP course is often the first step.

Now, how does this tie into your instrument rating? Here’s the interesting part: of the total time you’ll need for the ATP, 75 hours of actual or simulated instrument time can count toward the IFR requirement in the ATP rules.

Corporate & Part 135 Reality Check

In corporate and charter flying, the job market typically expects you to hold a commercial certificate, an IR, and a fair chunk of total time.

There’s a legal basis for this, too. You’ll need 1,200 total hours, 500 cross-country, 100 night, and 75 instrument to fly as PIC (Pilot-In-Command) in a Part 135 operation.

And don’t forget instrument currency. How does that work? Well, you might have heard of the “6-6-6” rule.

Within the previous 6 months, you need six instrument approaches, holding procedures, and intercepting/tracking systems under actual or simulated IFR conditions.

If you go past that period, you can still regain your currency, but this time with a safety pilot, flight instructor, or in a simulator.

Now, if another 6 calendar months have gone without meeting those minimums, you can only regain instrument currency through an Instrument Proficiency Check (IPC).

Insurance Matrix

Insurance is a less glamorous topic, but it’s extremely practical. Underwriters often set minimums for experience in the specific make/model and whether you are instrument-rated.

For example, a Cirrus SR22 policy might quote a “qualified pilot” at a premium of around US$500 to US$650 per year (liability only). But if you are not instrument-rated or have lower experience, the premium might jump to US$900 to US$1,142 per year.

8. Decision Matrix: Choose Your Best Path

After everything we’ve just talked about, it essentially all boils down to two questions: How much cash do you have now? And, how strict is your career deadline?

If you have enough funds at the start and you’re working against a deadline (say, you want to hit the airlines ASAP), then doing the instrument rating first could be your best bet. You absorb the up-front cost, but you maximize your chances of meeting hiring windows.

If you don’t have the funds now but your timeline is more relaxed, you could mix strategies. Begin commercial or modular training while planning for your instrument rating shortly after.

Pressed for both cash and time? It would be best to begin commercial training first and defer the instrument rating. You’ll accept limitations, but hey, any progress is progress! And there are work opportunities that don’t require an IR where you can earn and save up for the rating.

Now, if both your cash flow and timeline are flexible, doing IR training first gives you breathing room. You preserve cash early and build experience. Then, you can invest in commercial training when you’re ready.

9. Common Questions

Still have some questions on your mind? Let’s answer the FAQ’s when it comes to certification, and debunk the most common myths.

“I can legally haul freight VFR at night without IR.”

The confusion begins with 14 CFR 61.133(b)(1), which states that passengers for hire cannot be carried on cross-country flights over 50 NM or at night.

Notice how that wording only mentions passengers, not property or cargo? You may think this allows you to haul freight at night, but not so fast.

For Part 135 operations, you can’t act as PIC without an IR unless you’ve got an ATP certificate. Yes, even for VFR flights. So, when does hauling freight get into Part 135 territory?

It usually happens when the operator runs a charter or on-demand cargo business. The flights also go beyond short local routes, often crossing long distances or entering airspace that requires IFR.

In these cases, the operator needs a Part 135 certificate to fly legally. Once you’re under that operation, flying freight at night or past 50 NM without an IR is simply off the table.

“Will my CPL training get delayed if I fail the IR knowledge test?”

No, failing the instrument knowledge test (or any, for that matter) will not block your commercial eligibility.

Suppose you fail a knowledge or practical test. In that case, you’ll just need additional training from an authorized instructor who deems you ready to pass, and then get an endorsement from your instructor before retesting.

Failing the IR knowledge just means you’ll need to do a bit of extra work and endorsement before your retake.

Conclusion

Choosing whether to earn your instrument rating before or after your commercial certificate isn’t about right or wrong. It’s about what fits your timeline, budget, and career goals.

Are you chasing airline hours, or are you building experience one weekend at a time? Regardless of which path you choose, the key is to stay consistent and intentional with every flight hour.

Each rating opens new doors, and every checkride sharpens your skills as a professional aviator. So take the path that aligns with your mission.

Plan your training wisely, and trust that every logbook entry is another step toward the cockpit career you’ve been dreaming of.