-

Key Takeaways

-

Who Needs This Guide?

-

Ground Icing 101: Why Frozen Contamination Kills Performance

- Regulatory Framework

-

What Is De-Icing?

- Fluids & Equipment

- One-Step vs. Two-Step Procedures

-

What Is Anti-Icing?

- High-Viscosity Fluids (Type II/III/IV)

- Calculating Holdover Time (HOT)

- Exceeding HOT: Options & Legalities

-

Putting It Together: Ramp-Side Decision Flow

- Pre-Spray Brief With Deicing Crew

- Cockpit Checklist Integration

-

Anti-Icing Equipment & Fluid Selection

- GA, Turboprop, Jet Differences

- Emerging Technologies

-

Case Studies & Lessons Learned

- Challenger N90AG, Birmingham 2002

- Phenom 300 N555NR, Provo 2023

-

8. FAQs & Misconceptions

-

9. Quick-Reference Resources & Tools

-

Conclusion

Ice doesn’t need dramatics to be dangerous. A thin film you can barely see can steal lift and mess with performance before you even notice.

Many winter incidents start with false assumptions made on the ramp. Was that frost really gone? Was that fluid enough? Did the clock already start?

This guide breaks down what each process actually does, and how to make clear and defensible decisions before takeoff.

Key Takeaways

- Deicing removes existing frost, ice, snow, or slush to restore clean aircraft surfaces.

- Anti-icing protects already clean surfaces for a limited time to prevent new contamination.

- Aircraft can be treated using heated fluids, infrared energy, mechanical means (like brushes), or by heating the aircraft.

- Always check surfaces and holdover time since expired protection has additional requirements.

Become a Private Pilot!

Train fast with bite-sized lessons and real test-style practice.

- 540+ videos; average lesson ~3 minutes.

- Several practice exams and 800+ questions.

- Study groups, fast instructor support.

- 30-day money-back + pass guarantee.

Who Needs This Guide?

You need this guide if you operate in weather where your aircraft is often vulnerable to icing, and you’re not always sure what action to take. Some situations look harmless at first glance, until you take a closer look.

You also need to think about your legal exposure. The clean-aircraft concept is a regulatory requirement. As pilot-in-command or dispatcher, you are responsible for making sure no frost, ice, or snow is adhering to critical surfaces at takeoff. That responsibility sits squarely on your shoulders.

We’ll proceed with the assumption that you already understand basic aircraft systems and standard operating rules. But you likely also haven’t had formal training in cold-weather or ground-icing operations.

Well, the good news is that all you need to know is your airplane and how to take action against icing.

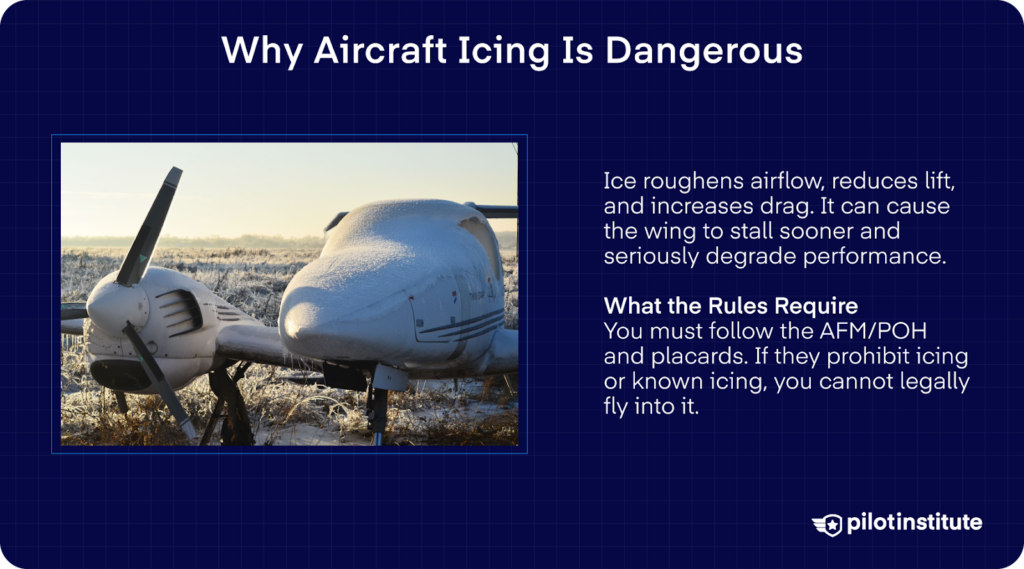

Ground Icing 101: Why Frozen Contamination Kills Performance

Icing can rob your aircraft of its performance capabilities at best. At worst, it can bring you to disaster.

But just how dangerous is aircraft icing? Ice, frost, or snow that sticks to the leading edges or critical surfaces changes the shape of the wing and tail. This frozen contamination roughens airflow and reduces lift.

It also increases drag and raises stall speed. Small amounts of ice can make it harder for the aircraft to climb and maintain speed.

The NTSB says no amount of snow/ice/frost should be considered safe for takeoff. And even with an ice protection system, performance losses still occur if you don’t remove contamination before flight.

Regulatory Framework

The icing rules you follow depend on what kind of operation you’re conducting. Parts 91, 121, 125, and 135 each define different responsibilities when icing is possible, but they share the same bottom line: you can’t operate in icing beyond what your regulations, your aircraft certification, and your approved procedures allow.

Part 91 contains the general operating rules for most GA flying, but not every section applies to every aircraft. § 91.527(Operating in icing conditions) is located in Part 91, Subpart F, which covers large airplanes, turbine-powered multiengine airplanes, and fractional ownership program aircraft (with applicability defined in § 91.501).

For aircraft and operations outside Subpart F, FAA guidance explains there are no single “one-size-fits-all” icing regulations written specifically for all other Part 91 GA aircraft. That does not mean “anything goes.”

Under § 91.9, you must comply with the operating limitations in the AFM/POH and placards. If your AFM/POH prohibits flight in icing (or requires specific equipment/procedures for icing approval), you are legally bound to follow those limitations.

For larger or commercial operations, the references are more explicit:

- Part 121: § 121.341 (equipment for operations in icing) and § 121.629 (operation in icing conditions, including holdover-time program requirements).

- Part 125: § 125.221 (icing conditions: operating limitations).

- Part 135: § 135.227 (icing conditions: operating limitations).

What Is De-Icing?

Deicing means taking action to remove any frost, ice, slush, or snow that is stuck on the aircraft before you depart.

How can you get rid of the contaminants? You can use fluids sprayed on the aircraft, heat to melt it, infrared energy to warm surfaces, or even mechanical tools like brushes and squeegees.

But most of the time, de-icing involves fluid. You’ll see trucks or carts fitted with sprayers that apply deicing fluid directly to the aircraft surface.

Fluids & Equipment

It’s common to heat the fluid before you spray it because heat helps melt and wash away contaminants more effectively. A heated application also reduces the time spent on the ground and slows the rate of ice reform.

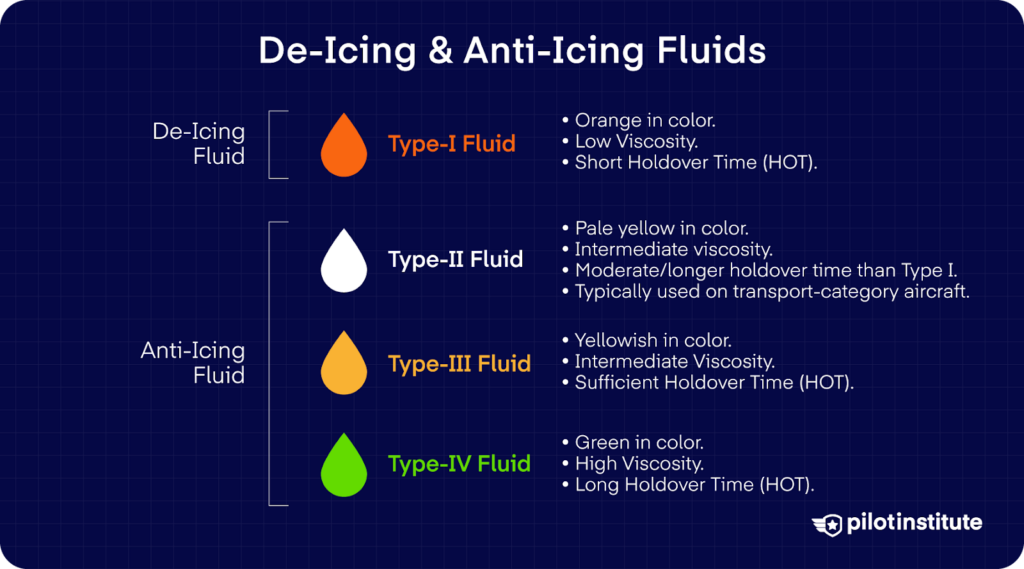

The most common fluids you’ll hear about are the SAE fluid types from I to IV. Each behaves a bit differently and has its own applications. Type I is used for de-icing.

One-Step vs. Two-Step Procedures

You’ll see special trucks at airports that have dual nozzles or even two separate tanks on board. These vehicles let ground crews switch quickly between deicing fluid and anti-icing fluid without changing equipment.

One-Step De-Icing

One-step de-icing and anti-icing uses a single application of heated anti-icing fluid. You spray the fluid to remove existing ice, and you leave it on the airplane surface to slow new ice from forming.

Two-Step De-Icing

Two-step de-icing and anti-icing breaks the job into two actions. The first step is pure de-icing. You apply heated fluid to strip away snow, ice, or frost from the critical surfaces.

The second step is anti-icing, and it happens after the surfaces are clean. You apply a separate overspray of anti-icing fluid, usually a thicker type, to protect those surfaces from new ice while you wait to depart.

What Is Anti-Icing?

Anti-icing helps you buy time. You use it to protect clean aircraft surfaces from frost, ice, snow, or slush for a limited window. That window is the holdover time (HOT), starts when the final deicing/anti-icing fluid application begins.

What does anti-icing actually do? It creates a protective layer on your aircraft that resists freezing precipitation while you taxi or hold short.

High-Viscosity Fluids (Type II/III/IV)

Types II, III, and IV fluids give you flexibility during anti-icing. You can apply them at 100/0, 75/25, or 50/50 concentrations, depending on conditions.

Type I fluid plays by different rules. Its holdover time is much shorter than Types II, III, or IV. Type I HOT is strongly dependent on applying heated fluid properly and can be shortened by high precip rates, wind/jet blast, or cold-soaked aircraft skin

How come? Because protection from Type I depends heavily on the heat absorbed by the aircraft’s surface during application. If the surface cools quickly, protection fades just as fast.

Calculating Holdover Time (HOT)

Why is it so important to know your holdover time? Well, remember that anti-icing fluid doesn’t stay active forever. The clock starts when the final anti-icing application begins and stops when the fluid’s protection is gone.

Any time past that and you’re back at risk of ice buildup until you reapply anti-icing.

1. Weather Conditions and OAT

How can you make sure you stay protected? Start by looking at the weather conditions at your location. You need to know the outside air temperature and the type and intensity of precipitation.

2. Fluid Type

Next, identify the anti-icing fluid you used. Each fluid type has different protection times. Type I fluids tend to give the shortest holdover times. Types II, III, and IV last longer because they are thicker and stick to the surface better.

3. Holdover Time Tables

Now, go to the official holdover time tables published by the FAA, or those followed by your operator, if applicable.

These tables list conditions down the left side, like temperature and precipitation type, and then columns with estimated protection times for each fluid.

Once you have the correct row for your weather and the matching column for the fluid you applied, read the number that represents the holdover time.

You’ll notice that it’s given as a range between two durations. So, which one should you follow?

The lower end of the time span is your worst-case planning value. It reflects how long protection is expected to last in moderate precipitation of the type listed.

The upper end shows the expected protection time in light precipitation of the same type.

4. Start the Clock

That number is your guide. Start counting from the moment the anti-icing application begins.

If you’re doing a two-step process where deicing comes first, start timing when the final anti-icing spray starts, not when the initial deicing spray begins, and not when the anti-icing spray ends.

Track the time carefully as you wait to depart. You should aim to complete your taxi and takeoff before the HOT expires.

Exceeding HOT: Options & Legalities

What happens if you exceed the maximum holdover time in the table? You can’t just go ahead. 14 CFR 121.629(c)(3) allows takeoff only if one of three things happens.

The first option is a pre-takeoff contamination check. This check confirms that the wings, control surfaces, and other critical areas defined in the program are clean.

The second option is an approved alternate procedure. The FAA must specifically accept this method and must still verify that all critical surfaces are free of contamination.

The third option is simple but time-consuming. You will have to reapply deicing and establish a new holdover time.

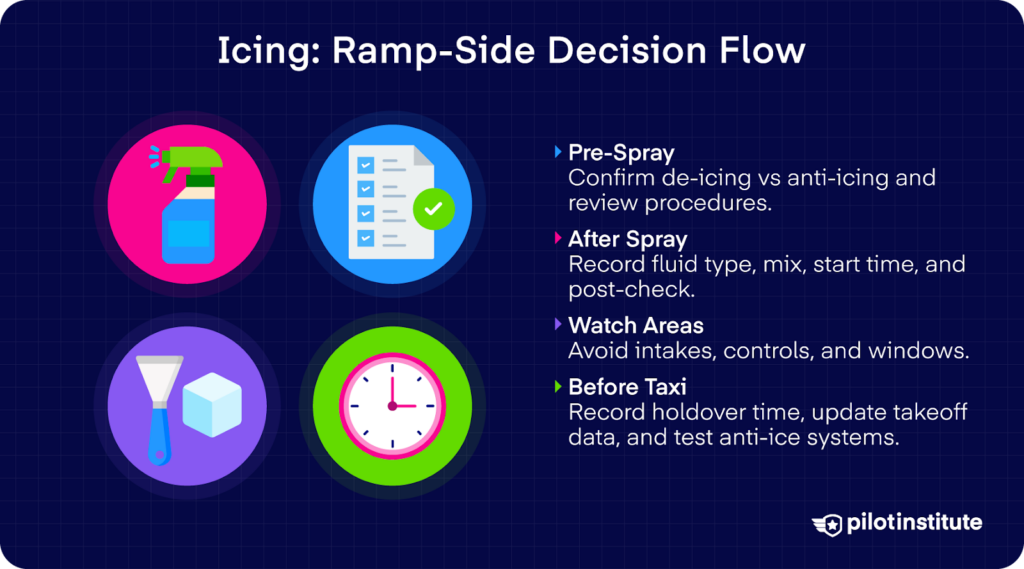

Putting It Together: Ramp-Side Decision Flow

Pre-Spray Brief With Deicing Crew

Remember that many deicers service multiple carriers, so clear communication is essential to make sure you and the ground crew are on the same page.

First, you should go over whether the aircraft needs deicing or anti-icing. Then, discuss the gate or remote deicing/anti-icing procedures and any aircraft-specific procedures.

Just before commencing the application of deicing/anti-icing fluid, ground personnel should confirm with the flight crew that the aircraft is properly configured for deicing.

Once the deicing/anti-icing is complete, the ground crew should provide you with the following information:

- The fluid type used

- The fluid/water mix ratio by volume (not required for Type I)

- The local time when the final fluid application began

- Confirmation that the post-application check was accomplished (specify and record the date)

Did you know that some parts of your aircraft must not come in direct contact with anti-icing fluids? You should minimize fluid entry into intakes, outlets, and control surface cavities.

Windows deserve special attention. Do not direct fluid onto the flight deck or cabin windows. These fluids can craze acrylic surfaces or seep past window seals. Either issue can leave you with distorted visibility.

Cockpit Checklist Integration

You want your cockpit checklist to flow with what’s happening on the ramp. One thing you must do right after anti-icing is to record the holdover time somewhere that’s easy to reference.

Even without contamination, cold conditions can change how your aircraft accelerates. Check your aircraft’s gross weight and confirm that any residual wetness or fluid won’t significantly increase drag or rolling resistance.

From there, modify your flight management system (FMS) takeoff data if required. You’ll need to update the takeoff weight if you’ve burned fuel during delays. Double-check that the rotation speed (Vr) reflects the updated weight.

Just before you release the brakes and begin taxiing toward the runway, it’s good practice to insert an anti-ice system test into your pre-departure flow.

Some aircraft have ice protection systems on engines or lifting surfaces that you can activate to check if they work properly.

Anti-Icing Equipment & Fluid Selection

GA, Turboprop, Jet Differences

Remember that Type I fluid is the thinnest option you will encounter. It blows or shears off easily, even at relatively low takeoff speeds. Because of that, you can use it on any aircraft.

Type II and Type IV fluids go in the opposite direction. They use thickening agents to increase viscosity. Their thickness lets the fluid stay on the aircraft longer, where it can absorb and melt freezing precipitation. You need a higher airspeed on takeoff to shear the fluid off cleanly.

Type III fluid is more niche and operator/location-dependent. It uses thickeners like Type II and IV, so it provides more protection than Type I. At the same time, it is formulated to shear off at lower speeds.

All that makes Type III well-suited for smaller commuter aircraft. But when conditions call for that middle ground, it can also work on larger aircraft.

Emerging Technologies

The world of deicing is evolving. Airports and service providers are investing in eco-advanced deicing technologies to cut environmental impact while boosting efficiency.

One example in ground support equipment is the introduction of electric deicing trucks. Aero Mag claims that their truck cuts emissions by a lot when compared to the traditional diesel unit.

These trucks produce 87 percent less greenhouse gases, and that adds up to around 35 tons of carbon dioxide saved each year just for one truck!

Infrared technology is also changing ground deicing. Focused infrared energy can deliver enough heat to contaminated surfaces to remove ice effectively. When used as part of an FAA-approved ground deicing program, it becomes a legitimate alternative to fluid-based deicing.

Infrared systems use little to no freezing point depressant fluid during the deicing step. The benefit? Less chemical runoff and lower overall fluid use on the airport.

Case Studies & Lessons Learned

Challenger N90AG, Birmingham 2002

On January 4, 2002, a Bombardier Challenger 604, registration N90AG, was preparing to depart Birmingham on a non-scheduled passenger flight to Bangor, Maine.

The airplane had been parked outside overnight in below-freezing temperatures. Other airplanes on the ramp showed obvious contamination the next morning, and later evidence confirmed this airplane was no different.

Both pilots completed exterior inspections, and yet, no de-icing happened. The crew continued with frost still clinging to the wing surfaces.

What happened next? Well, the takeoff roll itself looked normal. But seconds after liftoff, the airplane rolled aggressively to the left in clear daytime conditions.

The airplane crashed inverted within the airport perimeter and was destroyed by impact forces and a post-crash fire. All five occupants perished.

You can tell where the flight crew went wrong. They failed to ensure the wings were clear of frost before departure.

Frost roughened the wing surface and reduced the stall angle of attack. The margin disappeared so quickly that the stall protection system couldn’t stop the left wing from stalling.

But at the end of the day, this was a very preventable accident. The failure to recognize and correct icing on the airplane before takeoff led directly to disaster.

Phenom 300 N555NR, Provo 2023

An Embraer Phenom 300, registration N555NR, was preparing to depart Provo Municipal Airport in Utah. The jet had spent the night in a heated hangar. Then, the airplane sat outside for about forty minutes in snow and mist after refueling, with no deicing or anti-icing applied.

Witnesses noticed water droplets on the wings before departure, and yet, the flight crew still went on with the takeoff roll.

At rotation, the airplane pitched up, then rolled sharply to the left. Within moments, it crashed just beyond the runway. The left wing struck first, and then the airplane was destroyed. The pilot didn’t survive, and others were seriously injured.

What did the investigators find? The Phenom 300 had a wing and horizontal stabilizer anti-icing system designed to prevent or remove ice from the leading edges.

The system was available, but it wasn’t used correctly. Flight data showed the anti-ice was briefly turned on during preflight, then switched off and left off through the takeoff sequence.

The aircraft’s POH clearly says that contaminated surfaces must be de-iced before departure. When freezing precipitation is present, ground crews should apply anti-ice. Pilots also need to make a visual contamination check within five minutes before takeoff.

Unfortunately, none of that happened.

The National Transportation Safety Board identified the probable cause clearly. The pilot failed to deice the airplane before takeoff. Ice stayed on the wings, so it reduced the lift. With that, the stall margin shrank.

The result? An aerodynamic stall during the initial climb, followed by the abrupt left roll and loss of control.

8. FAQs & Misconceptions

Is Type IV a de-ice or anti-ice fluid?

The short answer is it depends. All fluid types have been used as both deicing and anti-icing agents. Type IV is often used as an anti-icing fluid, similar to Types II and III. Type I fluids are normally considered deicing fluids.

However, Type I fluids don’t work as well as Types II, III, and IV when used as an anti-icing agent. Also, heated and diluted Types II and IV fluids are being used for deicing and anti-icing operations.

It’s just raining at +1°C, do I need de-icing?

Yes, you do. Precipitation like rain or drizzle at temperatures just above freezing can still contain supercooled droplets.

Supercooled droplets are liquid even though the air temperature is at or slightly above 0 °C, and they freeze on impact with surfaces that are colder, such as the wing and tail.

That frozen layer can destroy lift and dramatically change how the aircraft performs during takeoff.

Taking off with polished frost is okay.

Well, it used to be, but not anymore. In Docket No. FAA-2007-29281, Notice No. 08-06, the FAA proposed removing language that had long allowed takeoff with “polished frost” on critical surfaces.

That wording used to exist in Parts 91, 125, and 135, and it let pilots smooth frost before flying. But in February 2010, the proposal took effect.

Why not just polish it smooth? Because there is no reliable way to turn frost into a clean wing. Even thin, smooth frost still counts as contamination. Any frozen layer, no matter how subtle, increases risk during takeoff.

9. Quick-Reference Resources & Tools

- FAA Ground Deicing Program (Issue 3)

- Ground Deicing and Anti-Icing Program (AC No. 120-60B)

- Pilot Guide: Flight in Icing Conditions (AC No. 91-74B)

- ICAO Manual of Aircraft Ground Deicing/Anti-Icing Operations (Doc 9640-AN/940)

- NASA Glenn Research Center Aircraft Icing Training Courses and Resources

- NASA Glenn Research Center Ground Icing Decision-Making Flow Chart

- FAA Holdover Time Guidelines (Winter 2025-2026)

- APS Holdover App

Conclusion

Ground icing discipline comes down to a simple flow. Remove contamination first so the aircraft starts clean. Then, protect clean surfaces so new ice does not undo that work before takeoff. And lastly, verify and double-check so you won’t get caught by assumptions.

Make the clean-aircraft mindset part of your normal operation, rain or shine.

Run short table-top deicing drills before winter starts. Talk through timing and decision points while the pressure is low.

Ice never sleeps, and neither should your vigilance for ground icing.