For a passenger, aviation law is a concept that receives little thought during a flight. To a pilot, however, aviation laws are the rules by which they operate to ensure the highest level of safety.

Different restrictions apply to different types of flights, and they can often create confusion. In this article, we’ll explain the three primary regulations that apply to aircraft operations: Part 91, Part 121, and Part 135.

Key Takeaways

- Part 91 covers general aviation with minimal restrictions.

- Part 135 regulates charter and commuter flights with stricter rules.

- Part 121 governs airlines with the highest safety standards.

- Ops Specs set FAA-approved rules for Part 121 and 135 operators.

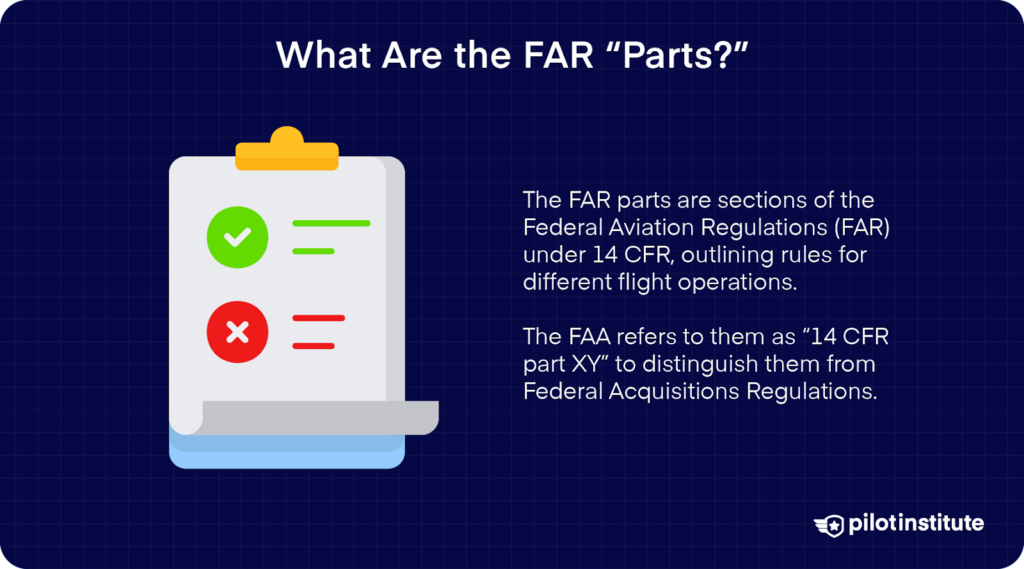

What Are the “Parts?”

Despite us pilots considering ourselves the epitome of human perfection, few are bar-certified lawyers. Somewhat understandably, there has been much confusion over the CFR, FAR, and parts thereof. Let’s explain.

The “parts” refer to the parts of the Federal Aviation Regulations (FAR). The FARs are found under Title 14 (Aeronautics and Space) and Title 49 (Transportation) within the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), which is US Federal Law.

It is important to note that Title 48 of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) is titled “Federal Acquisitions Regulations” (also FAR).

The two identical acronyms have created confusion, leading the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) to refer to regulations as “14 CFR part XY.”

To summarize:

- The Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) is US Federal Law.

- The Federal Aviation Regulations (FAR) are included within the CFR under Titles 14 and 49 as federal law.

- The “parts” referred to are parts of the FAR.

- The FAA refers to the parts of the FAR as “14 CFR part XY,” not “FAR part XY,” as it is colloquially used.

Hopefully, this summary has shed some light on the messy (but very important) legal jargon behind the rules of the air.

Now, let’s shine the torch on the differences between three of the most critical parts of the FAR.

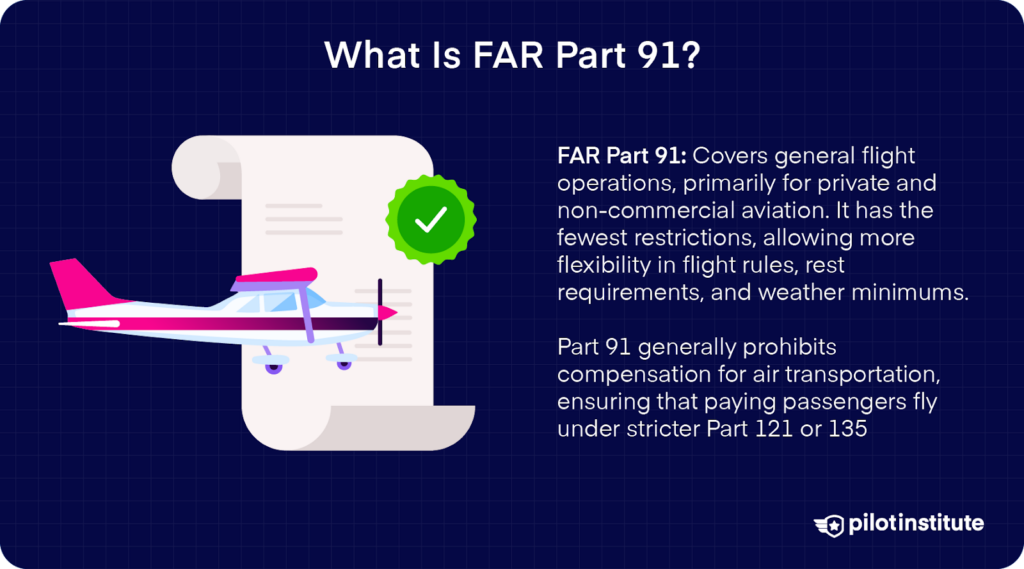

What Is FAR Part 91?

Part 91 concerns general operations and flight rules. General aviation operations fall into this category—think of a private pilot flying with his friends or family.

Part 91 is the least restrictive of the three parts of the FAR concerning aircraft operations. Part 91 also effectively prohibits compensation for air transportation by only allowing it in a minimal set of circumstances, even then limiting the amount paid.

This constraint upholds air travel safety standards by ensuring that paying passengers fly only on more restrictive (and, in effect, safer) Part 121 and Part 135 operators.

Counterintuitively, Part 91 concerns the general rules under which all aircraft operate unless trumped by more restrictive laws that apply to their respective operation.

For example, all part 91 restrictions apply to a part 121 operator, but the more restrictive part 121 rules trump their part 91 counterparts.

But what are the most common restrictions that apply to parts 121 and 135, but not 91?

For one, the energy drink and coffee guzzling pilots of part 91 have no legally required rest periods, meaning they can fly their aircraft for days on end without ever taking a break.

Under parts 121 and 135, however, this is not the case, and pilots must adhere to strict rest schedules to ensure that they are not fatigued during their operations.

Another example is weather minimums. A part 121 or 135 crew cannot legally initiate an approach if the weather is below minimums. Under part 91, however, they are free to do so.

Part 91 is also more relaxed when it comes to security. Passenger identification is not required for domestic flights under part 91.

For part 121 or 135 operations, passenger identities need to be verified by the operator, and passengers who are at least 18 years old will be required to provide photo identification.

What Is FAR Part 135?

Part 135 details the regulations for commuter operations and on-demand operations (also known as charters).

Part 135 only applies to aircraft with 30 or fewer seats or a maximum payload capacity of 7,500 pounds, including commercial helicopter operations (other than external loading (i.e., a helicopter sling), which is covered by part 133).

Think of private jets, charter flights, small turbo-propeller aircraft, and commercial helicopters – these are usually part 135 operation aircraft.

An important distinction must be made between the part under which an operation falls and the aircraft it uses.

A charter company, for example, may be able to fly their turbo-propeller aircraft under part 91 for a repositioning flight with no passengers, allowing fewer restrictions on that specific flight.

Then, when an aspect of part 135 is met (such as a paying passenger onboard), their ops spec for part 135 is enforced.

What Is FAR Part 121?

Part 121 details the rules for the big boys – scheduled air carriers.

Think of regional and major airlines such as Delta, Southwest, American, SkyWest, and large cargo aircraft operated by FedEx or UPS.

The FAA’s definition of a scheduled operation is at least “5 round trips per week on at least one route between two or more points according to the published flight schedule.”

Part 121 is the most restrictive of the three parts and is considered the highest commercial air travel safety standard.

One of the most notable distinctions between parts 121 and 135 is the requirement for two pilots on a part 121 operation vs. the allowance for one pilot on a part 135 operation.

The Pilot in Command (PIC) on a part 121 operation also shares operational control with a flight dispatcher. In contrast, the PIC on a part 135 operation can assume complete operational control of the flight.

Operations Specifications (Ops Specs)

One fundamental difference between part 91 and part 121 or 135 operators is the requirement of operations specifications (commonly referred to as “ops specs”) for part 121 and part 135 operators.

Ops specs are an FAA-approved framework for how an air carrier will operate. They can be more restrictive than the laws detailed in parts 121 and 135, but never less.

Ops specs detail every aspect of an airline’s operation, from the approval of Electronic Flight Bags (EFBs) to what airports an airline is allowed to use.

Some airports, for example, can be used for refueling or diversions but not for regular use. Another example would be the ability to use CAT II Instrument Landing System (ILS) approaches, allowing less visibility during landing than CAT I ILS approaches.

How an airline is allowed to operate in their ops specs are determined by an FAA Principal Operations Inspector (POI). The POI is the head of a division within the FAA tasked with determining how an air carrier is allowed to operate.

How much freedom an air carrier receives is determined by many different factors. If the POI feels that the air carrier is inexperienced or has a poor safety record, they may restrict certain aspects of their operation to improve safety.

Conversely, if the POI feels that the air carrier demonstrates good safety standards, it may allow for more operational capability.

Two air carriers operating the same aircraft may have vastly different operational capabilities according to their respective ops specs. One air carrier may have better-trained pilots and upgraded equipment, allowing them to perform procedures that another air carrier will not be able to, for example.

Conclusion

The regulations created and enforced by the FAA have made air travel the safest form of transport available.

The FAA has created the different parts of the FAR to maximize the scope of which air and cargo travel is available while maintaining a high standard of safety.

If you are a pilot, the part under which you operate and your ops specs are your bread and butter, some parts of which you should know by heart.

If you are a passenger, rest assured that the rules and regulations ensure that you are kept safe, no matter with whom you fly.