-

Key Takeaways

-

1. What Is an MEL

-

2. MEL Basics: Definition and Philosophy

- Where the MEL Fits in the Airworthiness Chain

-

3. Regulatory Foundations

- MEL Path

- Non-MEL Path

- When an MEL Becomes Mandatory

-

4. From MMEL to Your MEL: Development and Approval

- The Approval Process

- “O” & “M” Procedures Attachment

- Keeping The MEL Current

-

5. Anatomy of an MEL

- ATA Chapter Organization

- Rectification Interval Categories

-

6. Using an MEL In Daily Operations

- Five-Step MEL Decision Process

- Multiple Defects and Interactions

- Communication Chain

-

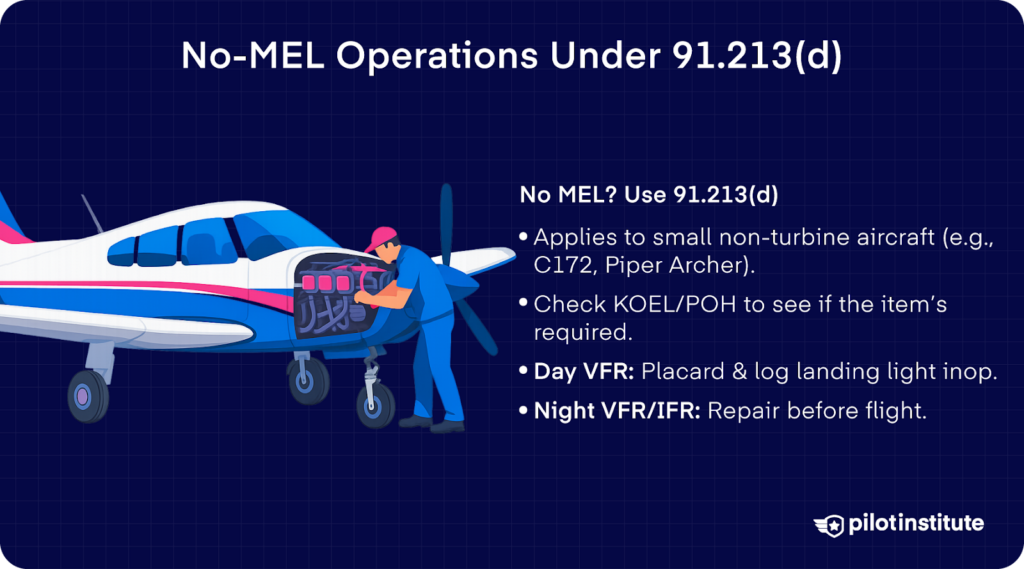

7. No-MEL Operations Under 91.213(d)

- Eligible Aircraft

- KOEL & Equipment List Method

-

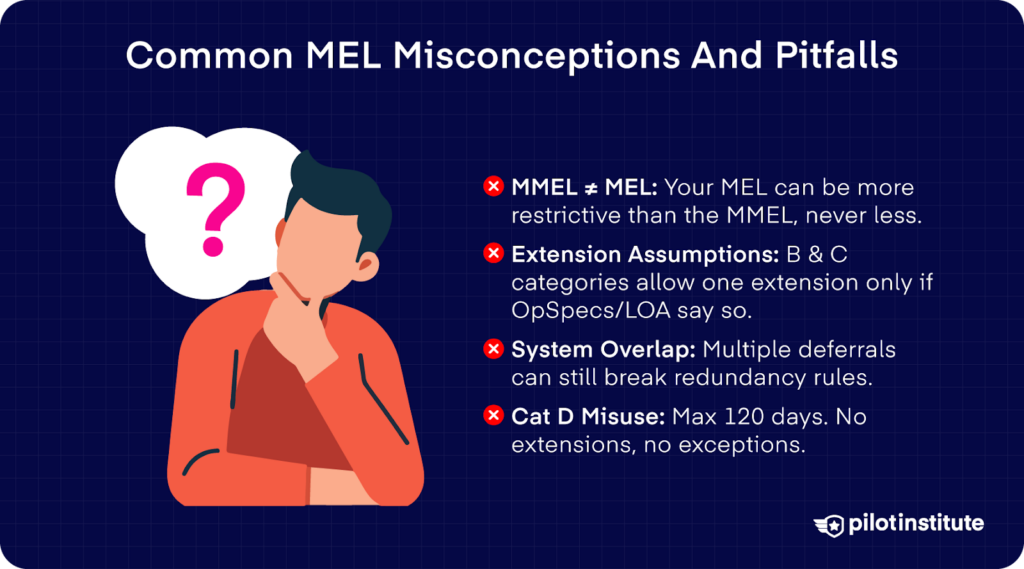

8. Common MEL Misconceptions and Pitfalls

- “MMEL = MEL”

- Ignoring Extension Paperwork

- Overlooking Related Systems

- Treating CAT D as “Indefinite”

-

9. Best Practices For A Strong MEL Culture

- Training & Recurrent Drills

- Digital Tools

- Recordkeeping & Audit Prep

-

Conclusion

So you have a flight at dusk, and your aircraft is ready for departure. As you begin pushback, a mechanic waves you down. One of your landing lights just failed.

The clock is ticking, and your passengers watch anxiously. Can you go ahead legally?

Modern aircraft are built with layers of redundancy. Regulators know that not every system must work for an aircraft to fly safely.

That’s where the Minimum Equipment List, or MEL, comes in. It’s your guide on which items can be inoperative, under what conditions, and for how long.

Let’s talk about when an MEL is required, how it’s structured, and a systematic process for using it. By the end, you’ll know how to make the call without second-guessing.

Key Takeaways

- The MEL allows certain inoperative equipment as long as the aircraft remains safe and airworthy.

- Under 14 CFR 91.213(a), you cannot depart with inoperative equipment without an FAA‑approved MEL.

- 14 CFR 91.213(d) conditionally permits non‑turbine and small aircraft to operate without an MEL.

- Strong MEL culture requires regular training, accurate recordkeeping, and proactive communication across the entire operation.

1. What Is an MEL

Are you a student pilot? If so, the MEL will teach you the logic behind aircraft dispatch rules early. When something breaks on the ramp, you’ll already know which items can fly and which ones ground the aircraft.

As you move up to private or commercial pilot flying, MEL awareness becomes your shield against unnecessary risks to your certificate.

Mechanics also rely on the MEL every day. It guides logbook entries and deferrals to make sure they’re done correctly. It could even save your aircraft from downtime while keeping it airworthy.

Dispatchers and other flight operations staff benefit, too, because MEL familiarity allows them to make compliant decisions that prevent costly delays.

Even flight instructors find value in it. The MEL is a great tool to teach students about structured decision-making.

2. MEL Basics: Definition and Philosophy

| Document | Who Publishes | Covers | Legal Status | Flexibility |

| MMEL | OEM + FAA AEG | All equipment of a type | FAA-approved template | Broad, least restrictive |

| MEL | Operator | Installed equipment only | STC via LOA/OpSpec | More restrictive |

| KOEL | OEM | Equipment for each “kind of ops” | Part of AFM | Fixed |

| CDL | OEM | Missing external parts | FAA-approved | Structural focus |

| NEF | Operator | Non-essential furnishings | Company policy + FAA review | Highest flexibility |

Let’s say you’re prepping for a night flight and discover a cockpit light isn’t working. Normally, you’d cancel, but the Minimum Equipment List exists for just this kind of moment.

Let’s compare this scenario to the seatbelts in your car. Even if one is broken, every occupant will still need a belt. You can’t skip that safety requirement, even if everything else checks out.

FAA Advisory Circular 91‑67A explains that when certain equipment is inoperative, an approved MEL plus a Letter of Authorization (LOA) functions like a Supplemental Type Certificate (STC) for that aircraft.

Where the MEL Fits in the Airworthiness Chain

In the chain of command for aircraft certification, where does your decision to dispatch lie? Let’s take a look.

First, the Type Certificate sets your aircraft’s overall design and required equipment. Next, the Type Certificate Data Sheet (TCDS) spells out the details for your specific model.

Now, with these as a foundation, the FAA and manufacturer build the Master Minimum Equipment List (MMEL) together. It’s a broad template approved by the FAA that indicates which installed systems may be inoperative under limited conditions.

Then comes your Operator MEL, developed by your school or company. It’s based on the MMEL but tailored only to your aircraft’s installed equipment.

It’s reviewed and approved by FAA Flight Standards under OpSpec/LOA procedures. It can only be as restrictive or more than the MMEL, but never less.

Now, if we put these together, the chain reads:

Type Certificate → TCDS → MMEL → Operator MEL

When you defer a landing light and send an aircraft out legally with a known limitation, you’re simply following a line of certification and airworthiness authority.

3. Regulatory Foundations

MEL Path

You’re gearing up for departure when a cockpit instrument flickers out. Does your aircraft have an MEL? If so, 14 CFR 91.213(a) gives you a clear path to flight: the MEL path.

What does this involve? You’ll need an FAA‑approved Minimum Equipment List and Letter of Authorization on board, which together act like a supplemental certificate authorizing you to fly with certain inoperative equipment.

You must strictly observe every condition and limitation listed in both the MEL and LOA.

Non-MEL Path

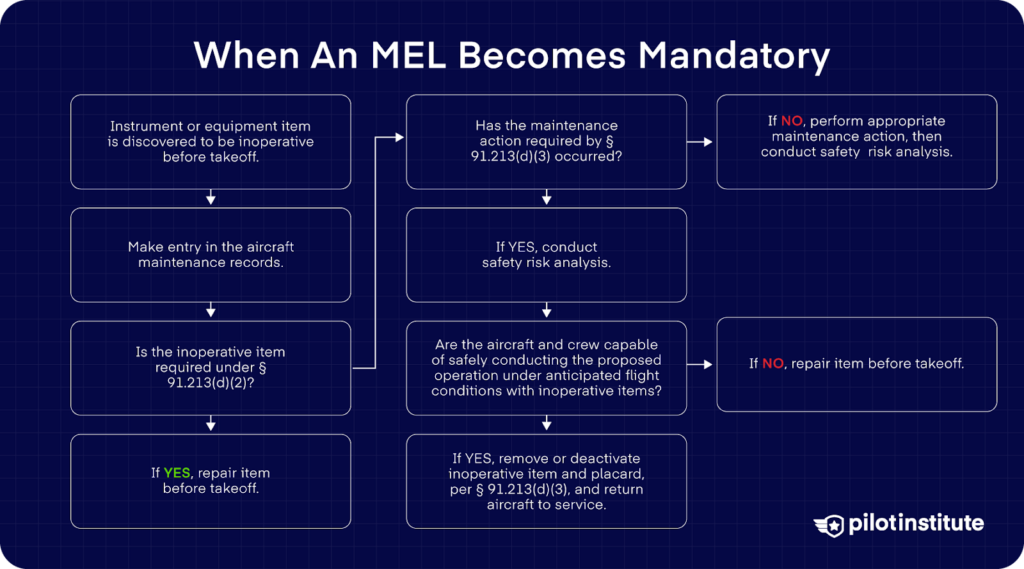

Now, if you’re flying a small, piston aircraft without an MMEL or MEL, or a category like gliders or balloons, you move down the non‑MEL path under 14 CFR 91.213(d).

You cannot defer items required by airworthiness directives, POH/KOEL, 14 CFR 91.205 VFR or IFR minimums, or certification standards.

Then, the broken component must then be either removed or placarded “Inoperative,” properly logged, and confirmed safe by a qualified pilot or mechanic.

This route requires no FAA MEL approval, but it demands strict compliance with maintenance and airworthiness documentation.

When an MEL Becomes Mandatory

Let’s make one thing clear: when you’re flying a turbine-powered aircraft, you simply must have an MEL with LOA.

If you’re in a multiengine aircraft covered by an MMEL, the same applies. You go the MEL path. Single-engine turbine? Also mandatory.

But if you’re in a small single-engine piston under Part 91, things get conditional: if no MMEL exists, you might fly under the non‑MEL 14 CFR 91.213(d) path, but only if you meet its strict criteria.

4. From MMEL to Your MEL: Development and Approval

When your operation crafts its own MEL, the first steps are clear. They delete any items not installed on your airplane and add any serial‑specific gear your equipment includes.

What do you get from this? A lean MEL specific to your aircraft. It’s based on the broad MMEL template but customized to your registration and configuration.

The Approval Process

How does an MEL get greenlit? Once your draft operator MEL is ready, the FAA approval process kicks in. For Part 91 and Part 135 operations, you submit via Letter of Authorization D095 or D195.

Draft → FSDO/CHDO review → FAA sign-off → STC status

D095

If you want an MEL approved under LOA D095, you need to submit a signed, written request to your local Flight Standards District Offices (FSDO) or Certificate Holding District Office (CHDO).

What should you add to your request? Here’s a sample provided by the FAA:

D195

If you’re applying for an MEL under LOA D195, the process is similar but has one key difference: you also need to submit a copy of your operator‑developed MEL with your request (electronic copies are preferred).

Your request should look something like this:

And another thing to add: if you already hold an LOA D095 and conduct international operations, you also have to mention that in your letter.

“O” & “M” Procedures Attachment

When you check your MEL, you might notice (M) or (O) symbols in the “Remarks or Exceptions” column. What do they stand for?

(M) Symbol

If you see an (M) symbol, it stands for a maintenance procedure. This procedure has to be completed before you can dispatch the aircraft.

Normally, certified maintenance personnel handle these tasks, but other qualified personnel can perform simpler tasks. Your MEL should also include the step‑by‑step instructions for each (M) procedure.

(O) Symbol

If you see an (O) symbol, it indicates an operations procedure that must be done before flight. These are usually carried out by the flight crew, though other trained personnel can help when needed.

Some of these tasks are part of flight planning, while others require actions in the cockpit or relate to weight and balance and cargo loading, which may involve ground staff or load controllers.

Keeping The MEL Current

Finally, remember that your MEL is a living document. The FAA updates the MMEL regularly. If an MMEL revision is mandatory, operators must update their MEL within 90 days of release.

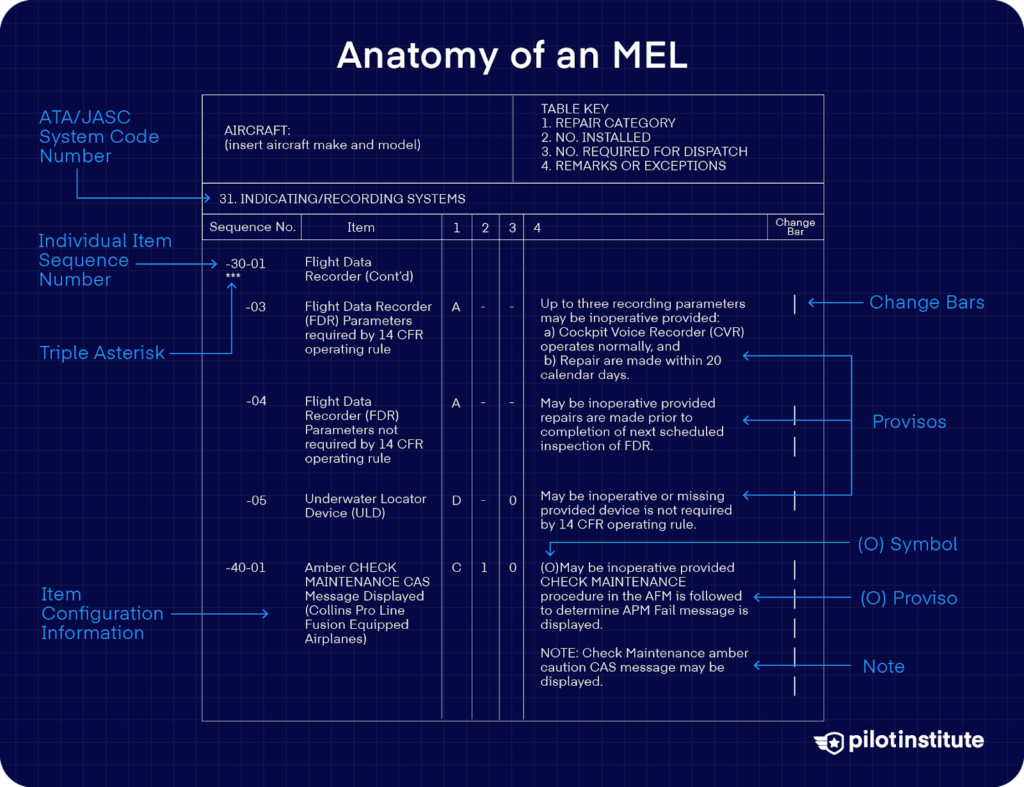

5. Anatomy of an MEL

Your aircraft’s MEL starts with a familiar structure, arranged by ATA chapters. These are the same codes used in maintenance manuals, like 33 for lights, 34 for navigation, and so on.

ATA Chapter Organization

You’ll see each chapter and system of your MEL neatly listed, followed by individual sequence numbers referencing installed equipment and the number required for dispatch.

It’s intuitive. You navigate by what’s broken and easily find the procedural steps and limitations associated with it.

You can imagine each ATA chapter as a filing cabinet drawer. When the MEL is organized by ATA codes (e.g., ATA 33, ATA 34), you know precisely where components like cabin lights or navigation lights must appear.

Within each chapter, you’ll find individual items numbered in sequence, followed by applicable (M) and (O) procedures and any 14 CFR‑required notes like “as required by 14 CFR.”

Rectification Interval Categories

| Cat | Time Limit | Extension? | Example Item | Common Trap |

| A | As stated | None | ELT battery | Forgetting “next flight after…” wording |

| B | 3 calendar days | One 3-day | One landing light | Crossing midnight at Zulu vs. local |

| C | 10 calendar days | One 10-day | VHF #2 | Miscounting day 1 |

| D | 120 days | Zero | Cabin reading light | Treating as “forever” |

Here’s where the MEL converts into a clock: each item falls into one of four repair category buckets, and each has a standard interval.

Category A

Category A is the real wildcard. You’re bound by the time written in the remarks, and no extensions allowed.

For example, an ELT battery that must be replaced “as stated,” and a missed replacement means no takeoff at all.

Category B

Category B gives you three consecutive calendar days (72 hours), excluding the day you discovered the defect.

Many people mistakenly start counting from the hour, but FAA guidance is clear. If you log it at, say, 10 a.m. on January 26, your 3‑day window starts at midnight January 27. You’re allowed one single 3‑day extension, but that’s it

Category C

Category C buys you 10 calendar days (240 hours), also starting at midnight the next day and allowing one single 10‑day extension.

The most common trap here is starting “day 1” on the day of discovery instead of the calendar shift.

Category D

The time limit gets stretched to 120 calendar days in Category D. No extensions accepted and no surprises. They’re established by the FAA in MMEL policy and codified in advisory guidance.

Want to include repair‑interval letters in your MEL? The A, B, C, and D repair categories you see in the MMEL don’t actually apply to a custom MEL made by an operator. What you do need to follow are any specific time limits listed in the MMEL notes.

But regardless, any broken or missing equipment must be properly dealt with. They need to either be fixed, replaced, removed, or inspected by a certified maintenance personnel at the next scheduled inspection.

6. Using an MEL In Daily Operations

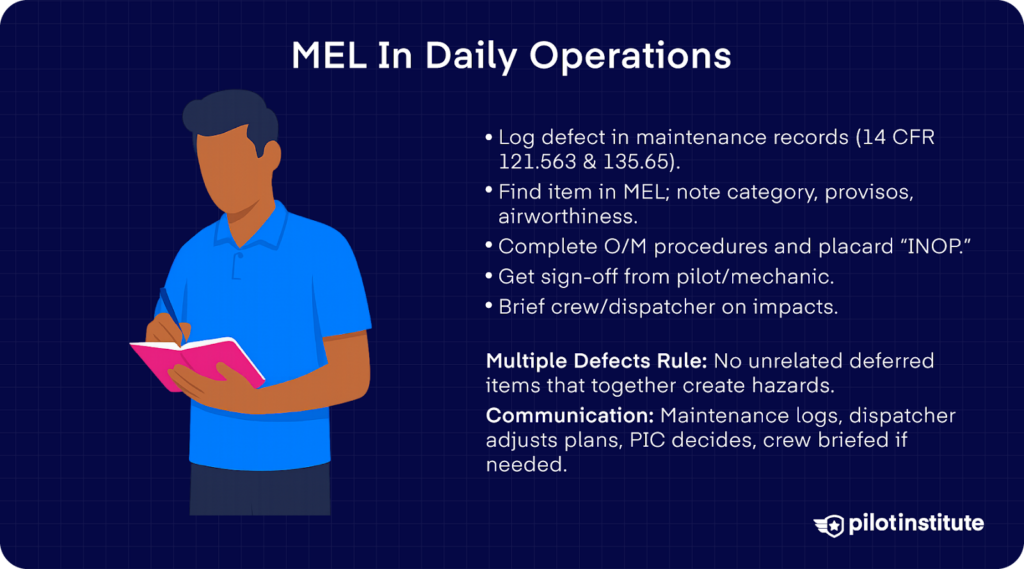

Five-Step MEL Decision Process

When a piece of equipment goes dark on your aircraft, you don’t want to panic. What’s the best way to make calm and accurate decisions? Have a system, and this is where the five-step decision process comes in handy.

First, you discover the defect, then you write it in your aircraft’s maintenance log immediately. This isn’t something “nice to have.” You are legally required to do this, as per 14 CFR 121.563 and 135.65.

After that, reference your MEL index to locate the correct system and item number. You read the MEL entry carefully and track the category (A, B, C, or D). Note any provisos and confirm the airworthiness conditions.

Afterwards, complete O or M‑coded procedures. A final check or circuit‑breaker collaring, a mechanic’s or pilot’s sign‑off goes alongside the “INOP” placard in the cockpit.

Finally, you brief your team—captain, dispatcher, even cabin crew, and sometimes passengers—if it changes anything on your flight procedures.

Multiple Defects and Interactions

Here’s a rule often missed: “No flight shall be conducted with multiple unrelated deferred items that create a hazard.” That wording comes verbatim from your MEL preamble, and it’s an FAA red flag.

Operators have been tripped up when deferring items that individually meet requirements but collectively fail safety-of-flight expectations.

On January 8, 2003 Air Midwest Flight 5481 crashed shortly after takeoff due to misrigged elevator controls and an aft center of gravity.

During prior maintenance, the required trim tab functional check was deferred under MEL authority instead of being completed, which concealed the control deviation.

Communication Chain

When it comes to communication, you are responsible, but you’re not alone. Who are the players involved in this chain?

Maintenance control must log the deferral, and your dispatcher needs to know to coordinate turnaround plans and fuel loads. That said, the final go/no‑go decision lies with you, the PIC.

Then, the cabin crew get briefed if the delay or equipment affects passenger safety or service. In every case, the MEL deferral stays visible via placards and entries in both the deferral and flight logs until repair concludes compliance.

7. No-MEL Operations Under 91.213(d)

Let’s say you’re doing your walk-around on your Piper Archer when you notice the landing light isn’t working. But in this scenario, there’s no MEL on board because this isn’t an airline operation.

Do you cancel the flight, or can you still go legally? This is where 14 CFR 91.213(d) gives you a clear path forward.

Eligible Aircraft

This rule applies to a specific group of aircraft: non‑turbine fixed‑wing airplanes weighing 12,500 pounds or less, along with gliders, balloons, and other lighter‑than‑air types.

If you’re in a piston single like a Cessna 172 or Piper Archer, you’re in 14 CFR 91.213(d) territory.

KOEL & Equipment List Method

Flying without an MEL doesn’t mean you can ignore inoperative equipment. After the MEL, you use the Kinds of Operations Equipment List (KOEL) or the aircraft’s equipment list in the POH. This tells you exactly what’s required for the type of operation you’re planning.

Let’s stick with the Piper Archer example. For Day VFR, the landing light isn’t required, so you could legally placard it inoperative, log it, and go.

But for Night VFR or IFR, that same landing light becomes required under the KOEL and 14 CFR 91.205, which means you’ll need to repair it before departure.

8. Common MEL Misconceptions and Pitfalls

“MMEL = MEL”

You spot a MEL item marked “not required by MMEL” and think, “Great, that’s not really required.” That’s the “MMEL equals my MEL” trap.

In reality, your operator’s MEL must never be less restrictive than the FAA‑approved Master MMEL. If your aircraft includes an optional avionics system not in the MMEL, the MMEL says nothing about it, but your MEL can.

Ignoring Extension Paperwork

Then, there’s the paperwork trap: ignoring extension procedures. Categories B and C allow a single extension, but only if your OpSpecs or LOA clearly authorize it.

An operator leaned back on Day‑3 documentation and assumed “one more three‑day extension is fine.” But since their OpSpec didn’t explicitly authorize even that first extension under the operator’s MEL, FAA enforcement treated that second extension as nobody’s business, all limits exceeded.

Overlooking Related Systems

A different beast emerges when systems share functions. Let’s say you defer a VHF‑2 radio and a nav/COM autotune switch.

You look only at each MMEL line individually, but forget the MMEL preamble warning: “don’t have multiple unrelated deferred items that degrade system redundancy.”

No single item violated its repair category, but the combination violated safety. When deferring anything, always think at the level of entire systems, not just item-by-item.

Treating CAT D as “Indefinite”

Last (but definitely not least) are Category D items. Part of you whispers, “That’s Cat D—that’s up to 120 calendar‑day repairs—let it ride.” But as AC 120-125 reiterates about Category D:

“This category item must be repaired within 120 consecutive calendar days (2,880 hours), excluding the day of discovery.”

Yes, you can initially approve a Cat D deferral, but no extensions beyond the original 120 days, even if the wording allows for some “grace.” If the 120-day clock runs out, the item must be fixed, or you can’t legally dispatch.

9. Best Practices For A Strong MEL Culture

If you want a team that doesn’t freeze at the first “INOP” sticker, what you’re aiming for is a thriving MEL culture. You’ll want confidence and fluency every time something fails.

Training & Recurrent Drills

Under 14 CFR 121.375, “Each certificate holder or person performing maintenance or preventive maintenance functions for it shall have a training program to ensure that each person (including inspection personnel) who determines the adequacy of work done is fully informed about procedures and techniques and new equipment in use and is competent to perform his duties.”

In practice, this could mean something as simple as running quarterly tabletop drills. Beyond knowing the five-step process, they encourage collaboration because real-world failures don’t happen in isolation.

Digital Tools

Want to ditch paper MELs and avoid a scramble during dispatch? High-reliability operators lean into EFB-based platforms:

- SkyBook eMEL: integrates seamlessly into your limiter/dispatch system. Tap through a MEL category, view conditional notes, and even simulate rectification timers directly from your iPad.

- CAMP eMEL (also called CAMP “live”): often used by carriers and fractional ops. It pushes Cat B deadlines into your maintenance dashboard, flags upcoming extension requests, and syncs deferral lists across teams—even between flight crew and your maintenance tracking system.

- FAA’s DRS portal: the same regulatory documents you’d search in the FSDO’s DRS website are now available on your tablet or phone. It’s always up-to-date and easily searchable.

Recordkeeping & Audit Prep

Let’s say you want to know when your Category B landing light deferral expires. Instead of shuffling through a paper logbook or calling maintenance control, you already have everything ready. You’ll save a lot of time with a clear log entry, a photo of the “INOP” placard, and the matching dispatch note.

Operators who handle audits well often keep a deferred‑item dashboard. This is a simple list that tracks every MEL deferral, its repair category, the expiration date (in local and Zulu time), and whether an extension has been approved.

Updating it each day, especially for short‑interval items like Categories B and C, prevents any surprises when a deadline approaches.

A monthly self‑audit also keeps the system reliable. Compare the dashboard with your MEL pages and your D095 LOA or OpSpecs to verify that every deferral is still compliant.

Conclusion

A properly used MEL does more than keep the FAA happy. It keeps your schedule intact and gives you a clear path forward when something stops working.

If you want to strengthen your MEL skills, start small. Download the MMEL for your aircraft, choose one item, and walk through a mock deferral with your crew.

Discuss the notes, check the “O” and “M” procedures, and decide how you would handle it in real time.

At the end of the day, a well‑understood MEL is not just regulatory paperwork. It is your license to operate with the assurance that you’re always legal and safe.