-

Key Takeaways

-

What Is Spatial Disorientation?

- What Is the Most Important Sense for Spatial Orientation?

- Spatial Disorientation

-

Organs Involved in Spatial Disorientation

- Vestibular System

-

Types of Spatial Disorientation

- Somatogyral Disorientation

- Somatogravic Illusions

-

Visual Illusions in Spatial Disorientation

- Aerial Perception Illusions

- Other Illusions

- How to Avoid These Illusions

-

How Pilots Can Avoid Spatial Disorientation

-

Conclusion

Spatial disorientation can catch even the most experienced pilots off guard. In the air, your brain isn’t designed to handle the conflicting signals between what you see, what your inner ear senses, and what your body feels.

This is where things get rocky. You might think you’re flying level, but you’re actually in a dangerous bank. Or you could feel like you’re climbing, but you’re really on the verge of a dive.

These disorienting moments can happen more often than you think, especially when visibility is poor.

Keep reading, and you’ll start to recognize the subtle tricks your body can play on you when you’re in the cockpit.

Key Takeaways

- Spatial disorientation mainly occurs in low-visibility conditions.

- There are three types of illusions: somatogyral, somatogravic, and visual.

- Pilots should ignore their “gut” and trust their instruments.

- Prevention is better than the cure. Avoid flying in IMC and low visibility conditions.

What Is Spatial Disorientation?

To understand spatial disorientation, you first need to know what spatial orientation means.

Spatial orientation is your body’s way of figuring out where you are and how you’re moving in 3D space. Your brain does this automatically by using signals from your eyes, ears, and body.

Normally, you use things like the ground or the horizon to help you know what’s up, down, or level. But in an airplane, especially in low visibility, you can’t rely on those usual reference points.

The movement of the airplane can confuse your body’s senses, making it hard to tell which way you’re going. That’s when disorientation or tricky illusions can happen.

Your brain gets orientation information from three systems:

- Your eyes (what you see).

- Your ears (how your inner ear senses motion and balance).

- Your body (feelings from your skin, muscles, and joints).

Usually, your brain combines these signals to figure out your position, but in flight, these signals can get mixed up. That’s why it’s important to trust your instruments when flying!

What Is the Most Important Sense for Spatial Orientation?

Visual information is the backbone of spatial orientation. Which means your eyes are the most important sensory organ.

Your brain feels in control when you can see the horizon or a steady reference point. That’s why pilots with a clear view outside hardly ever feel disoriented.

Spatial Disorientation

Now that you know what spatial orientation is, let’s talk about spatial disorientation in aviation.

Spatial disorientation happens when your eyes, ears, and body send mixed signals to your brain. The textbook definition is:

“The inability of a pilot to correctly interpret an aircraft’s attitude, altitude, or airspeed in relation to the earth or another reference point.”

This is especially common when flying in IMC (Instrument Meteorological Conditions)—like clouds or fog—when you can’t see outside. The mismatch between what you see (or don’t see) and what you feel can make you become disoriented.

Why is this a big deal?

If you get disoriented, you could lose control of the aircraft. This can often lead to serious accidents, like controlled flight into terrain (CFIT), which happens more often than you might think.

Why do pilots lose control?

It’s because what your body feels doesn’t always match what the aircraft’s instruments are telling you. Your instincts might say one thing, but in the cockpit, it’s vital to trust your instruments over your gut.

Even though today’s flight instruments are highly accurate, ignoring your instincts can be tough. But remember, when you’re flying, your gut feeling isn’t always your best guide!

Organs Involved in Spatial Disorientation

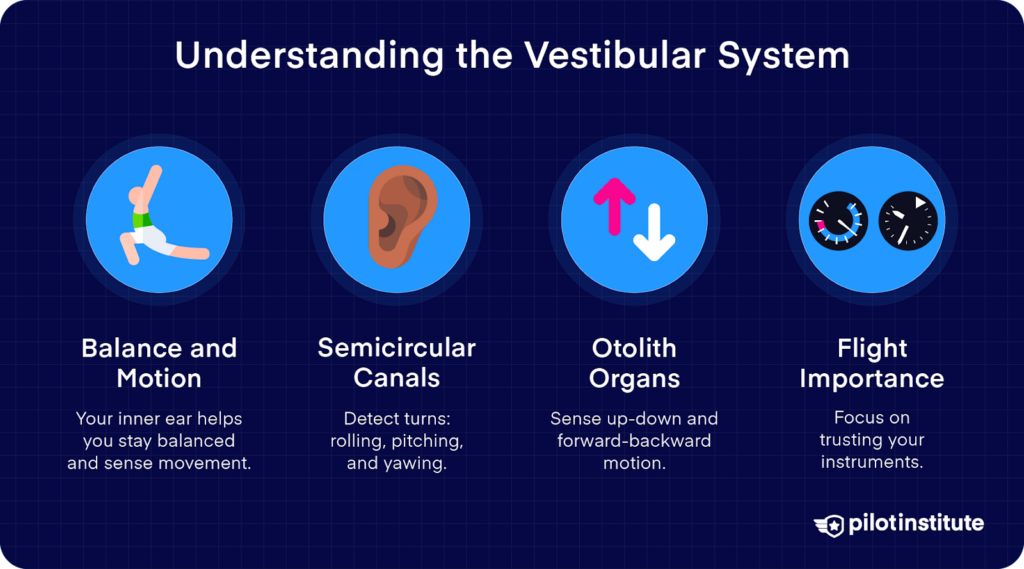

Vestibular System

Pilots need to know how the human body works, this is especially true when it comes to balance and motion.

Let’s break it down so it’s easy to understand.

Your inner ear keeps you balanced, and it’s part of what’s called the vestibular system, also known as the organ of equilibrium. This system helps you figure out how your body is moving in space.

The vestibular system has two main parts:

- Semicircular Canals

- Otolith Organs

What Are the Semicircular Canals?

Think of the semicircular canals as three tiny curved tubes in your ear, like a set of gyroscopes. They detect when your head moves in different directions:

- Rolling (side to side).

- Pitching (nodding up and down).

- Yawing (turning left or right).

Each tube is filled with a liquid called endolymph and has a motion sensor called the cupula, which has tiny hairs. When you move, the liquid shifts, bending the hairs, like wind blowing through tall grass. This tells your brain you’re moving.

The catch is that the canals can only sense quick turns (faster than 3 degrees per second). Slower movements might not register, which can lead to confusion during flight.

What Are the Otolith Organs?

The otoliths are another part of your inner ear that sense linear acceleration. Like moving in a straight-line.

- The saccule senses up-and-down movements.

- The utricle senses forward-and-back or side-to-side movements.

These organs are super important for knowing whether you’re climbing, descending, or accelerating.

Why Does This Matter?

It’s a lot to take in, but understanding these systems will help you recognize and manage vestibular illusions.

These illusions can happen in flight and when you can’t see outside. They can trick your brain into thinking you’re moving in ways you’re not.

Trust me, this knowledge will be useful later in your flight training!

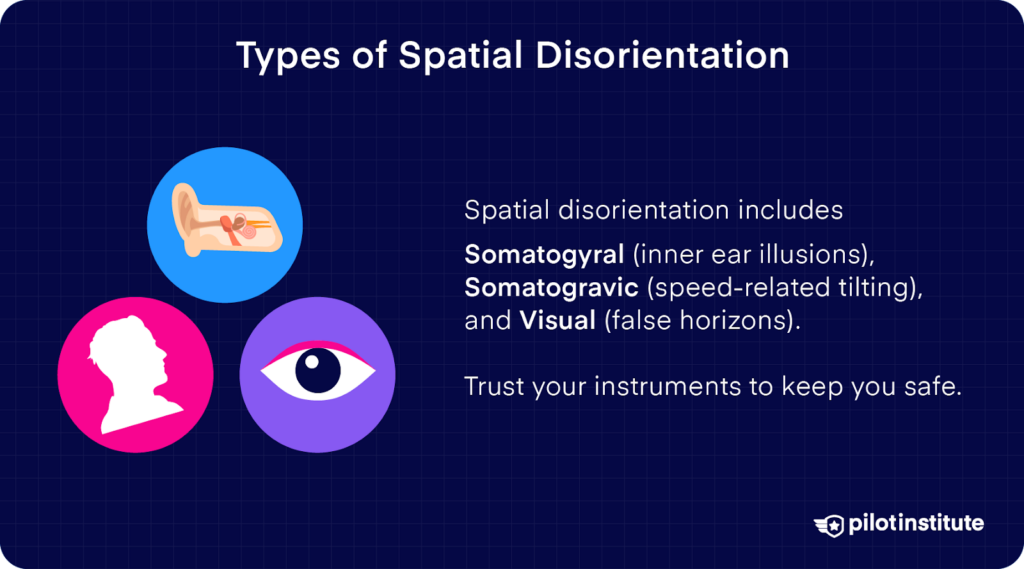

Types of Spatial Disorientation

There are three main types of spatial disorientation:

- Somatogyral Disorientation: Related to the semicircular canals.

- Somatogravic Disorientation: Related to the otoliths.

- Visual Disorientation: Involving visual illusions, such as false horizons.

Are you ready? Let’s look at each in detail.

Somatogyral Disorientation

When you don’t have visual references, your inner ear can trick you into feeling false rotations.

Here are four common illusions:

The Leans

The most common illusion. After a slow or prolonged turn, your inner ear stops detecting the motion. When you level the airplane, it feels like you’re turning the other way, making you want to lean back into the original turn.

Fix it: Trust your instruments, not your body.

Graveyard Spiral

This happens when you fall for the leans and re-enter a turn thinking you’re flying straight. As the aircraft loses lift, pulling back tightens the turn, causing a deadly spiral toward the ground.

Fix it: Watch your instruments to stop the spiral.

Graveyard Spin

If you recover from a spin, your inner ear may trick you into feeling like you’re spinning the opposite way. Reacting to this can send you back into the original spin.

Fix it: Trust your instruments to recover correctly.

Coriolis Illusion

Abrupt head movements during a turn can make you feel like you’re tumbling. It’s similar to the dizzy feeling you get when spinning in a chair and tilting your head.

Fix it: Avoid sudden head movements in IMC.

Somatogravic Illusions

This topic might seem technical, but let’s simplify it.

Your inner ear (otolith) can get confused by changes in speed and gravity while flying, causing these illusions:

- Head-Up/Head-Down Illusions: Speeding up can feel like you’re tilting up, making you want to push the nose down, which is risky during takeoff. Slowing down can feel like you’re tilting down, leading to overcorrection and possible stalling.

- Inversion Illusion: Switching from a climb to level flight can feel like you’re spinning, which might make you lose control and dip the nose too far down.

- Elevator Illusion: A sudden upward rush of air can feel like the airplane is climbing, tempting you to tilt down, risking a dive.

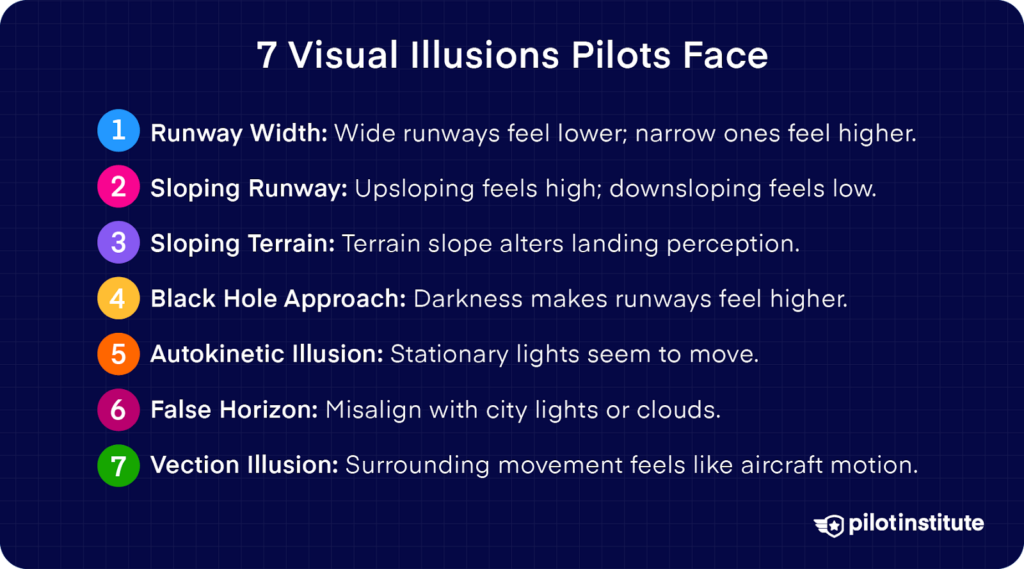

Visual Illusions in Spatial Disorientation

While having visual references will mostly prevent spatial disorientation, the eyes are not foolproof. Seven types of visual illusions can affect the way you fly the aircraft. They are:

- Runway Width

- Sloping Runway

- Sloping Terrain

- Black Hole Approach

- Autokinetic Illusion

- False Horizon

- Vection Illusion

Let’s look at each one in detail. We have another great article on ICEFLAGS that you should check out.

Aerial Perception Illusions

Pilots use a mental image of a “normal” runway to judge their approach. When the runway looks different, it can lead to dangerous illusions. Here are the most common ones:

Runway Width Illusion

- Wide runway: Feels lower than you are, causing you to pitch up and risk stalling.

- Narrow runway: Feels higher than you are, leading to a steep descent and faster landing.

Sloping Runway Illusion

- Upsloping runway: Feels high, causing a low approach and risk of terrain collision.

- Downsloping runway: Feels low, leading to a high approach and possible missed landing or stall.

Sloping Terrain Illusion

- Upsloping terrain: Feels high, risking a short landing or early flare.

- Downsloping terrain: Feels low, causing you to overshoot the landing spot.

Black-Hole Approach

At night, a well-lit runway surrounded by darkness can feel higher than it is, leading to a dangerously low approach.

Other Illusions

Autokinetic Illusion

Staring at a stationary light in the dark can make it seem like the light is moving.

Fix it: Don’t fixate on one light—keep scanning.

False Horizon Illusion

In low visibility, you might align with a false horizon, like city lights or banked clouds, causing altitude loss or a stall.

Fix it: Trust your instruments, especially over featureless terrain or at night.

How to Avoid These Illusions

- Use visual aids like VASIs and PAPIs to guide your approach.

- Cross-check your instruments to stay on a stable path.

- Study runway and terrain details during flight planning

How Pilots Can Avoid Spatial Disorientation

Flying in low visibility can be dangerous, so here’s how to keep safe:

Trust Your Instruments

- Practice using your instruments and develop a strong scan, even during VFR training.

- In IMC, rely on your instruments, not your senses, to avoid illusions.

- If you feel an illusion, ignore it and focus on your instruments.

Experience Illusions Safely

- Try spatial disorientation exercises in a controlled environment, like a VR trainer.

- Everyone experiences illusions differently, so learning how they affect you helps you identify and fight them in flight.

Reduce Risks

- Avoid flying if weather conditions are worsening.

- Always plan ahead and know the terrain and airport layout. For example, if a black hole illusion is possible, be ready for it.

Conclusion

Spatial disorientation isn’t something you want to experience, but if you fly long enough, you probably will.

The sensations your body sends you during flight are not always reliable. Trusting your senses over your instruments can lead you into serious trouble.

The good news? You don’t have to fall victim to these illusions. Know what to look out for and understand how your body reacts to different flight conditions. You can stay ahead of disorientation and keep control of your aircraft.

Keep scanning your instruments, don’t make rash decisions based on your feelings, and you’ll keep yourself out of harm’s way.