-

Key Takeaways

-

What Is a Go-Around?

-

Top Reasons for Go-Arounds

- Unstabilized Approach

- Runway Not Clear

- Weather

- Technical Issues

- ATC Request

- Anytime Safety Is in Question

-

How Common Are Go-Arounds?

- Example of a Preventable Accident

-

How to Perform a Go-Around (Step-by-Step)

- Radio Calls

-

Frequent Go-Around Mistakes

- Not Recognizing the Need for a Go-Around

- Delayed Go-Around Response

- Improper Application of Power

- Improper Aircraft Configuration

- Loss of Situational Awareness

- Loss of Control

-

Private and Commercial Pilot ACS Standards

-

Conclusion

Statistics show that go-arounds are among the riskiest maneuvers in general aviation. If you need to prepare for the challenges of a rejected landing, you may find it more complicated than you thought.

Luckily, with knowledge and training, go-arounds can become second nature.

In this article, we’ll cover everything you need to know to make safe, controlled go-arounds every time.

Key Takeaways

- Go-arounds are an important, potentially life-saving maneuver.

- A bad approach results in a bad landing. The best choice is to abandon a bad landing and go around.

- Pilots avoid go-arounds because it is seen as an admission of guilt.

- Go-arounds have little margin for error. Practice helps to avoid poor performance.

What Is a Go-Around?

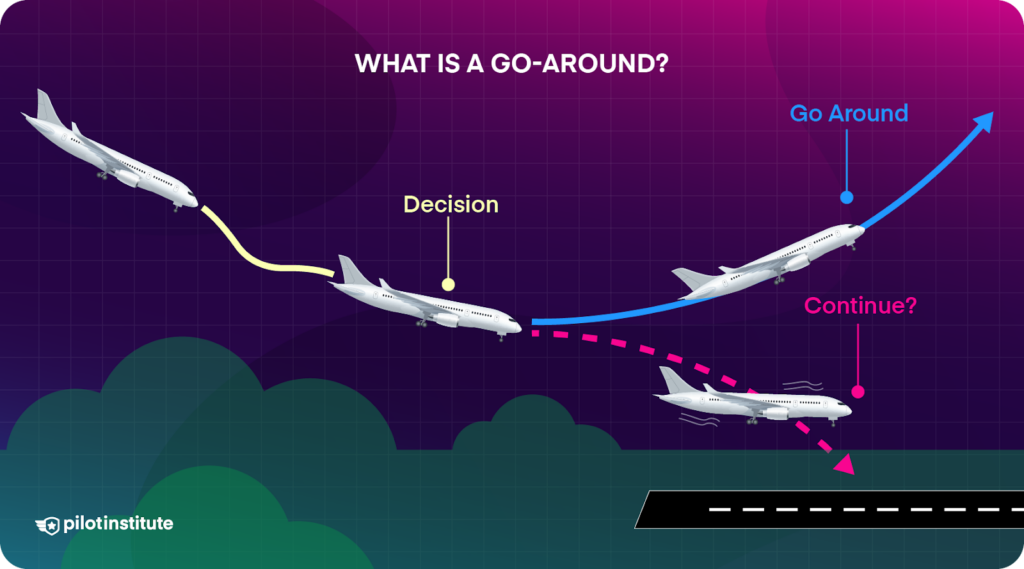

A go-around is a maneuver performed to abort or reject a landing on the final approach or once the aircraft has already touched down.

Pilots perform the maneuver when a landing is unsafe or can result in an incident. These include a runway collision, porpoising, bouncing, or possible overrun.

A pilot utilizes full power to perform a go-around, pitches the nose up, and climbs away as usual. It gives you another opportunity to come around and land.

A pilot can choose to go around at any point if they feel the landing is unsafe. ATC can also ask for a go-around if the landing runway is unsafe or for spacing reasons.

Top Reasons for Go-Arounds

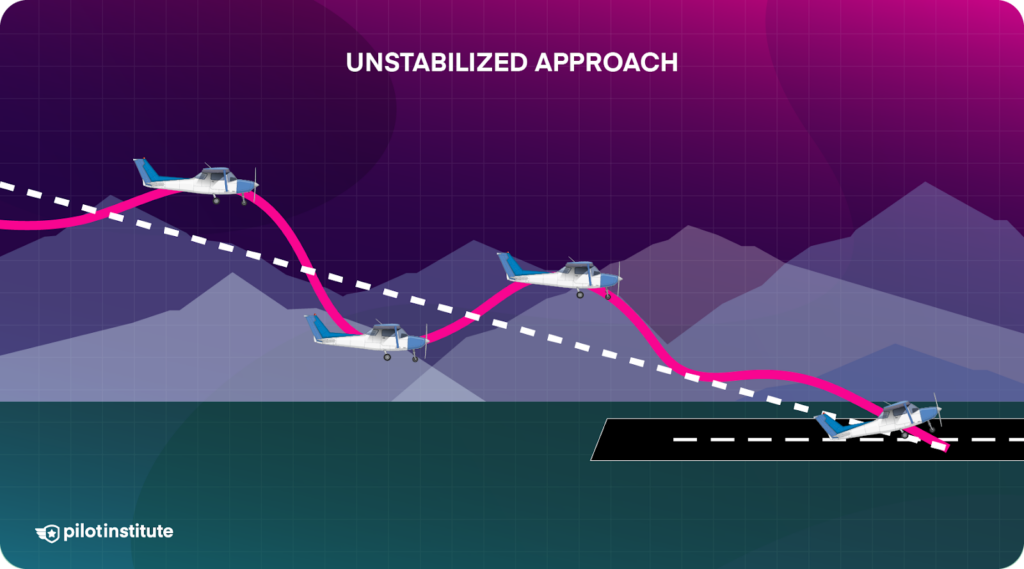

Unstabilized Approach

An aircraft must have a stabilized approach before landing. The main reason to go around is if the aircraft needs to be stable to land. In other words, it is an unstabilized approach.

Different reasons exist, but most of these result in an unstabilized approach.

An approach is stabilized when:

- The aircraft is on the correct flight path, i.e., on runway centerline and glideslope.

- Only small control inputs are required to maintain the correct flight path.

- All appropriate checklists and landing briefings are complete.

- Airspeed is not less than 1.3Vso +10/-0.

- The aircraft is in the correct landing configuration. The sink rate is less than 1000 fpm. If the landing requires a steep approach due to terrain, the pilot must brief it beforehand.

- Appropriate power setting to maintain airspeed and sink rate.

If the approach meets these criteria, it is considered unstabilized and is safe to land in such a manner.

If the approach is unstabilized, the pilot should initiate a go-around at a predetermined altitude. The FAA recommends 500 ft for VFR and 1,000 ft for IFR flights.

Runway Not Clear

A pilot should always go around when a safe landing is impossible. A go-around is necessary when the runway is obstructed, either by an aircraft or object.

An object colliding with the aircraft during a landing can be disastrous.

Weather

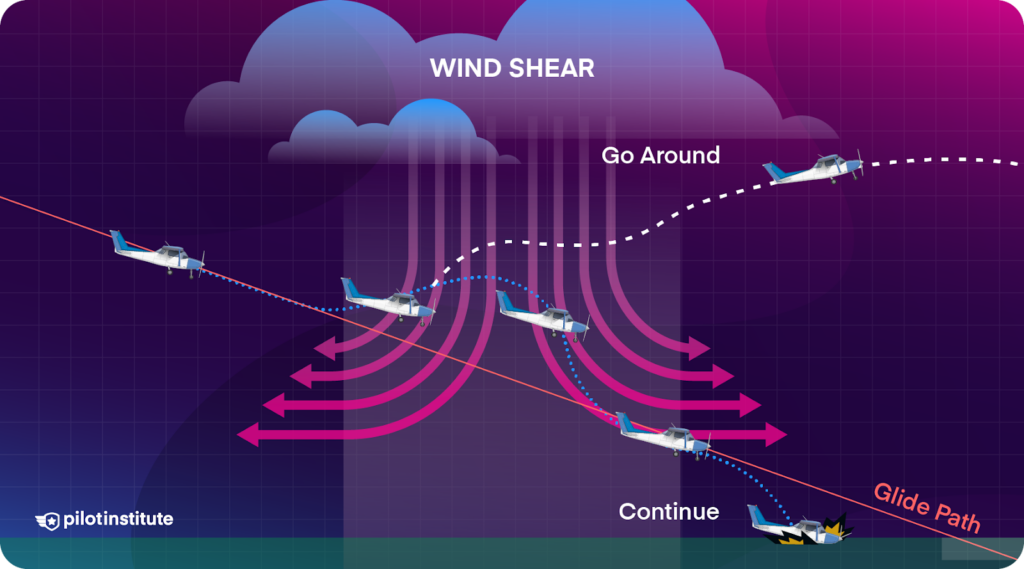

Go-arounds due to weather occur due to wind shear caused by gusting winds or microbursts.

When an aircraft encounters horizontal wind shear, it could be blown off centerline. Trying to make large corrections to return to the centerline is dangerous, so it’s best to go around.

Similarly, if an aircraft encounters vertical wind shear, it reduces or increases the sink rate. It can cause the aircraft to lose the glideslope, resulting in an unstabilized approach.

Technical Issues

Pilots can choose to go around if they are experiencing technical issues.

A common example is when pilots are unsure if their landing gear is down and locked. They will perform a low pass followed by a go-around so the tower can check if the landing gear is down.

ATC Request

ATC can request that an aircraft go around. ATC will request a go-around when there isn’t enough spacing or when a collision might be possible.

A common situation is if an aircraft is on final approach, and another holding on the runway cannot take off in time.

Anytime Safety Is in Question

Pilots must always act decisively to maintain a safe margin. If safety is compromised, the pilot must abandon the landing and try again.

Remember, correcting a bad landing is harder than maintaining a good one.

How Common Are Go-Arounds?

Pilots perform go-arounds, but not as often as they should. Many pilots avoid going around in favor of trying to wrestle the aircraft onto the ground. While possible, it’s a risky decision to make.

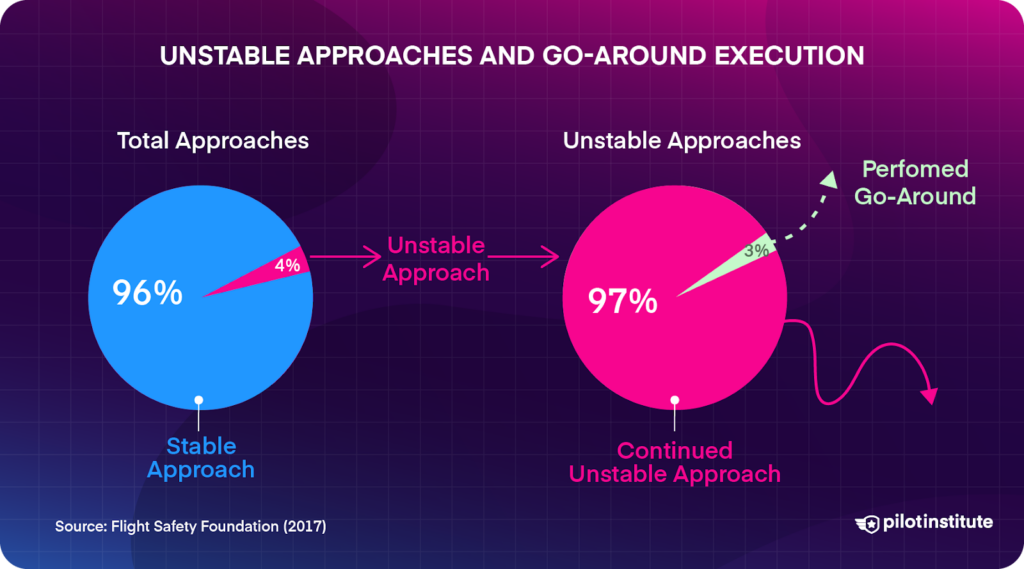

According to a study by the Flight Safety Foundation, only 3% of all unstable approaches result in a go-around. The study, titled “Go-around decision-making and execution project,” highlighted that failure to conduct a go-around is the number one risk factor in approach and landing accidents.

The reason is psychological. Instead of viewing a go-around as a corrective measure, many pilots feel it represents a lack of skill. They think that if they perform the go-around they are admitting that they screwed up.

They also find it embarrassing that others might question their skills and abilities.

Example of a Preventable Accident

A prime example of when a go-around could’ve prevented an accident is in the case of Southwest Airlines Flight 1455. The aircraft was 44 knots higher than its target landing speed, which resulted in a runway overrun. Many passengers were injured.

The NTSB later found that the crew continued the landing despite being unstabilized. If the crew had gone around, they could’ve returned for a safer, stabilized approach and landing.

Another example of when a go-around is required is this crash at Saint Barthelemy Airport (TFFJ). The video shows that the pilot was too high and too fast. However, they didn’t initiate a go-around. Instead, they hoped the aircraft would bleed off enough speed and altitude to land.

It didn’t, and the aircraft landed very far down the runway, bounced, and exceeded the runway length.

How to Perform a Go-Around (Step-by-Step)

Every pilot should have the go-around in their repertoire. They should also be well-versed in the maneuver to make it readily usable. Here’s how to do a flawless go-around every time.

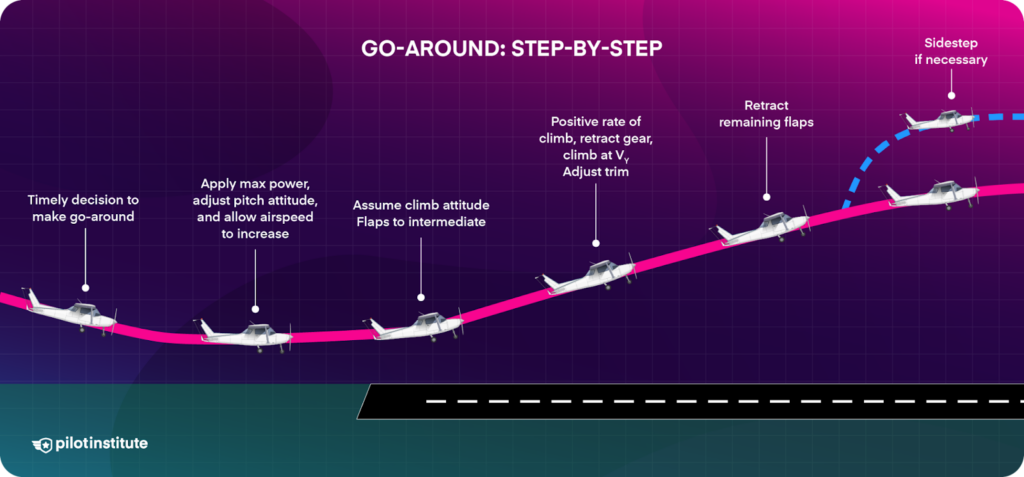

We’ll explain how to do the technique in a small single-engine aircraft, such as a C172. There are six main steps:

- Advance the throttles to full power.

- Pitch up for a climb-pitch attitude.

- Retract flaps.

- Establish Vx or Vy.

- Re-adjust trim.

- Side-step the runway.

The first three steps are the most important and can be easily remembered as power up, pitch up, and clean up.

Full Power

When performing a go-around, you want the most possible performance from the aircraft. So, you must advance the throttles to full power as soon as possible. It helps reduce the chances of a stall and puts you in a better position to arrest the descent and start your climb out.

Pitch for Climb

The next immediate action is to arrest the descent. Pitching back to a normal climb attitude will stop the aircraft from descending.

Retract Flaps

In a normal landing, the flaps should be at full. After adding full power and arresting the descent, the next step is to retract the flaps. You should immediately retract the flaps from full to 20 degrees.

Once you have a positive rate of climb, go from 20 to 10 degrees. Retract the flaps completely after clearing the obstacle and attaining your Vx or Vy. In IFR, retract flaps at the appropriate speed above 400ft AGL.

Re-adjust Trim

Many pilots trim the aircraft to maintain a steady nose-down attitude. So when you perform a go-around, the controls will be quite heavy. Once you have the aircraft climbing out and at a safe altitude, adjust the trim to make the aircraft easier to fly.

Side-step the Runway

The Private Pilot Airmen Certification Standards (ACS) asks applicants to show the ability to “Maneuver to the side of the runway/landing area to clear and avoid conflicting traffic.”

The main point to consider is whether there is traffic on the runway. If there is no traffic, use the runway as a reference to ensure you aren’t drifting due to wind.

However, if there is traffic on the runway, sidestep in the opposite direction of the traffic pattern. For example, side-step to the right in a left-hand pattern.

The side-step lets you maintain a visual and avoid the other aircraft’s climb path.

Radio Calls

When you perform a go-around, you must inform ATC. They will then adjust spacing and give you further instructions on rejoining the pattern while avoiding traffic. For instance, if an aircraft is on the crosswind leg, they’ll ask you to extend the upwind

If you don’t have the time, that’s okay. The order is aviate, navigate, then communicate. Make sure to communicate as soon as possible.

Frequent Go-Around Mistakes

If performed correctly, the go-around can prevent an accident. But, mistakes are often made during the maneuver, especially when a pilot is out of practice.

Not Recognizing the Need for a Go-Around

Choosing when to go around is one of the most important decisions a pilot can make. It’s an extension of good aeronautical decision-making (ADM). It’s also difficult for a pilot to admit that they’ve botched the landing and to abandon the landing.

The best method to determine if a go-around is necessary is to separate the landing into sections.

Approach

If the approach is unstabilized, choose a hard altitude to initiate the go-around. For example, if the aircraft is unstabilized at 200 ft, there isn’t enough time to make corrections. So, you should go around.

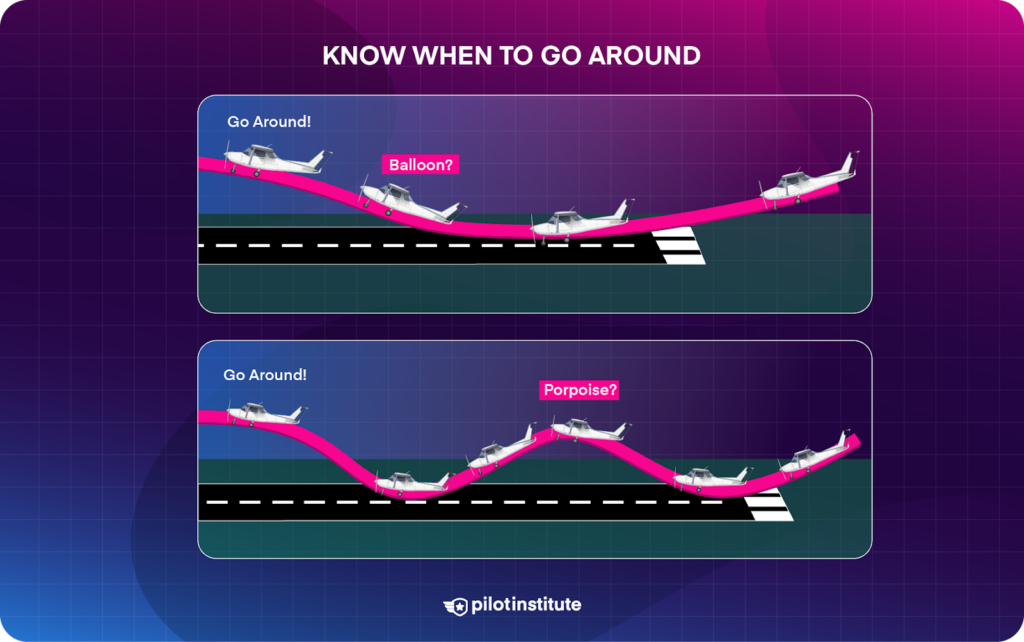

Roundout and Flare

Pick a point on the runway at which you will touchdown. If the aircraft hasn’t touched down by this point, initiate a go-around. For example, go around if the aircraft hasn’t touched down by the third runway centerline.

Another important decision to consider is if the aircraft bounces or porpoises. If so, immediately execute a go-around. Chances are you will overrun the runway. Even if you won’t, you could stall after a bounce or damage the landing gear while porpoising.

Delayed Go-Around Response

Another problem with go-arounds is poor response time. Once a pilot identifies the need for a go-around, it should be initiated promptly. Many pilots freeze when they realize their landing has gone awry, especially if the aircraft has already touched down.

Improper Application of Power

A pilot should advance to full throttle to get the most performance when beginning a go-around. Improperly applying power delays the process, increasing the risk of an accident.

Improper Aircraft Configuration

Properly configuring the aircraft during a go-around is vital. When going around, the pilot should immediately remove full flaps to reduce drag and increase performance.

Once a positive rate is established, reduce the flaps from 20 degrees to takeoff flaps (10 degrees). After obstacles are cleared and the climb-out speed is established, reduce the flaps to zero.

Reducing the flaps all at once will result in a large loss of lift, which can cause the aircraft to settle on the runway or stall.

Re-trimming the aircraft is also an often overlooked step. It makes the pilot work much harder, increasing mental and physical fatigue.

Loss of Situational Awareness

When a pilot is preoccupied with a difficult task, it’s possible to lose situational awareness. While going around, pilots should be aware of their surroundings, obstacles, and traffic.

Loss of Control

A stall is highly probable during a go-around, especially if the pilot doesn’t use full power or reconfigure the aircraft.

A stall is most likely if the pilot goes from landing flaps to zero flaps in one go. If a pilot stalls at a high power setting, the left-turning tendencies of the aircraft can cause it to go into a spin. At low altitudes, spins are unrecoverable and can lead to a loss of life.

Another issue is controlled flight into terrain (CFIT). CFIT is likely when the pilot does not pitch up adequately or if the aircraft stalls.

The risk of losing control is higher in instrument meteorological conditions (IMC) or at night. This is because the pilot no longer has a visual reference point to work with, i.e., the horizon. So, it’s important to use the flight instruments to maintain control.

Private and Commercial Pilot ACS Standards

During a checkride, you must perform a go-around. You must show the appropriate knowledge, risk management, and skills to do so safely.

According to the ACS, you should exhibit knowledge of the following:

- A stabilized approach and energy management.

- Effects of atmospheric conditions on a go-around, such as winds and density altitude.

- Wind correction techniques (side-skid or crab-and-kick)

They also seek good aeronautical decision-making. You must promptly execute the go-around while maintaining control and situational awareness. Radio calls and checklists are also expected when practicable.

The only tolerances for the maneuver are during the climb. You have to achieve and maintain Vx or Vy within +10/-5 knots.

Finally, you must maintain directional control and correct for any wind drift during the maneuver.

Conclusion

The go-around is a must-have in every pilot’s arsenal. When properly executed, it can be a potentially life-saving maneuver.

A pilot must be decisive, follow the procedure, and maintain full control during the maneuver.

Pilots tend to continue bad approaches rather than going around. The inability to abandon a bad approach can result in an accident.