-

Key Takeaways

-

What Is a Soft Field Landing?

- Why Do Pilots Perform Soft Field Landings?

-

Preparing for a Soft Field Landing

- Know the Field Condition

- Calculate Your Performance

- Insurance: Are You Covered?

-

Soft Field Landing Procedures (Step-By-Step)

- Approach Phase

- Roundout and Touchdown

- Rollout

-

Common Soft Field Landing Mistakes

- Unstabilized Approach

- Too Much Airspeed

- High Descent Rate

- Not Adding Power If Needed

- Releasing Backpressure on Touchdown

- Stopping the Aircraft with Brakes

-

Private Pilot and Commercial ACS Standards

-

Conclusion

Soft field landings are widely misunderstood.

They’re just like a normal landing but… softer, right?

Well, not exactly. There’s more to it than simply not landing hard.

Going into a checkride (or a grass strip) without solid soft field skills is asking for trouble.

Luckily, in this article, we’ll cover everything you need to know about soft field landings – including common mistakes that you should avoid.

Key Takeaways

- Soft fields are non-paved landing surfaces like grass, dirt, gravel, and sand.

- Landing on soft fields requires a specific technique for gentle touchdowns.

- Incorrect soft field technique can cause the aircraft to dig into the surface.

- Preparation and practice are key to successful soft field landings.

What Is a Soft Field Landing?

A soft field landing is a technique pilots use when landing on unpaved surfaces. The most common surfaces are grass, packed dirt, snow, sand, or gravel.

The soft field technique not only ensures the aircraft touches down gently. It also keeps the weight off the wheels for as long as possible.

Why Do Pilots Perform Soft Field Landings?

When landing on a soft surface, the wheels can easily dig into the surface or get bogged down. This may damage the aircraft or cause an accident.

If the nose wheel digs in at high speeds, it can result in a loss of control. In extreme cases, a nose-over can occur. High-wing aircraft with tricycle gear tend to be most susceptible to nose-overs. This tendency is due to their high center of gravity and heavy engine over the nose wheel.

The soft field technique is also useful on hard surfaces with cracks and potholes. It can decrease the wear and tear on the landing gear and tires.

Preparing for a Soft Field Landing

Preparation is crucial for a successful soft field landing.

Unlike paved runways, every soft landing surface is different. It’s important to know everything you can about the surface before you attempt to land on it.

Know the Field Condition

Before landing at a new location, check the condition of the surface. A soft touchdown can only do so much if the field is too muddy or has massive potholes.

You should also ensure that the surface is suitable for takeoff. A field with tall grass will slow you down quickly on landing. However, the increased drag might make it impossible to take off again.

Several hazards can make soft field operations challenging. Here are some to look out for:

- Grass: Check its height and if it’s wet or dry. Wet grass is slippery and can cause a loss of directional control.

- Mud: Check its depth and see if it’s wet or dry. Dry mud can cover a layer of wet mud or break during landing.

- Water: Look out for standing water, which can cause hydroplaning.

- Snow: The depth of snow can cause the aircraft to skid or get bogged down.

- Ice: Note the areas of ice accumulation and make plans to avoid these areas.

- Potholes: Deep potholes can cause tire punctures or damage the landing gear.

- Obstructions: Ensure the runway is clear of obstacles, from stones to animals.

Ground Inspection

The best way to check the field’s condition is by inspecting it in person.

If you intend to take off and land at the same field, the solution is easy. You can walk down the length of the runway. Before doing so, monitor the CTAF to ensure no aircraft are in the pattern or on final.

Is it too wet or muddy? Is the grass too long? Note any problem areas to avoid, such as potholes or dips. If you feel you can’t safely take off, canceling the flight is the best course of action.

However, if you’re flying to a soft field destination, you must check the condition by other means.

Check NOTAMs

Before departure, check the Notices to Air Missions (NOTAM) publication. You might find a NOTAM about your destination’s surface conditions. If the runway is too wet, it might be temporarily closed.

Don’t depend on NOTAMs to provide up-to-date information on soft field conditions. Many small airport managers don’t bother to publish field condition NOTAMs.

Call the FBO or Airport Manager

If you plan on landing at a small airport, call the FBO or airport manager ahead of time for a condition report.

Airport personnel perform visual inspections and know the problem areas of their airport. They’re happy to tell you the status of the airport and runways.

Crowd Source Information

The next best resource for information about runway conditions is other pilots.

As you approach the airport, monitor UNICOM for landing or departing traffic. When appropriate, ask about the field’s conditions.

If there is no traffic, you might be able to reach someone at the FBO who can help.

Low Pass or Touch-and-Go

What if the conditions are still unknown when you get to the airport? Take a closer look by performing a low pass or a soft touch-and-go. A touch-and-go lets you gauge the surface condition with a light tap of your wheels against the ground.

Transmit your touch-and-go intentions on the UNICOM frequency and fly a normal pattern. Keep your speed slightly higher than usual to ensure you don’t accidentally land.

Keep a few hundred RPM in during the roundout and flare. This keeps the wheels light on the surface when the aircraft touches down. If the wheels sink or you see water or mud, the field isn’t fit for landing.

Stick with a low pass if you’re not confident you can pull off this challenging maneuver.

Calculate Your Performance

Soft field and short field landings often go hand in hand since many unpaved runways are also short. Obstacles at either end often complicate matters.

Before engaging in soft field operations, you must check the aircraft’s performance. Calculate your landing and takeoff distances using the pilot’s operating handbook (POH). If your airport is too hot or high, you might be unable to land within the available distance and overrun the strip.

Another performance factor is the approach speed. The slower the approach, the shorter the landing distance. However, if you are too slow, you risk stalling the aircraft.

Many aircraft have specific recommended normal and short-field approach speeds. If the POH doesn’t specify an approach speed, you can use 1.3 VSO (stall speed in the landing configuration). This offers a slow enough speed for landing while keeping a decent safety buffer above the stall.

Using full flaps enables you to land at the slowest possible speed. However, the less speed you have, the less controllable the aircraft becomes. A faster, reduced-flaps approach improves aircraft control during strong crosswinds or gusts. Make sure to take that into account with your performance calculations.

Insurance: Are You Covered?

Insurers want to avoid as much risk as possible. And soft field operations are inherently riskier than hard-surface operations.

This unfortunate fact means your policy may not cover non-emergency off-airport landings. Should an accident occur, the insurer might deny a claim for damages.

Before heading out to any unpaved destinations, check your insurance policy.

Soft Field Landing Procedures (Step-By-Step)

Approach Phase

A soft field landing only differs from a normal landing on the final leg. So fly a normal pattern, complete your checklists, and turn base and final as usual.

Ask for a wind check if you’re flying at a towered airport or listen to AWOS at a non-towered airport. It will allow you to fine-tune your approach. If you’re at a field with no weather reporting, gauge the wind speed and direction using the windsock.

As with any landing, it’s vital to have a stabilized approach. Your sink rate, attitude, power setting, and airspeed should be steady. You should be on centerline with only small corrections required. If you’re not stabilized at 200 feet AGL, go around.

Finally, use the GUMPS checklist to ensure your aircraft is ready to land. This additional check helps prevent accidents like gear-up landings.

Fly the aircraft at the designated approach speed or 1.3 VSO, plus any gust factor. Use full flaps unless strong winds require a reduced flap setting.

Roundout and Touchdown

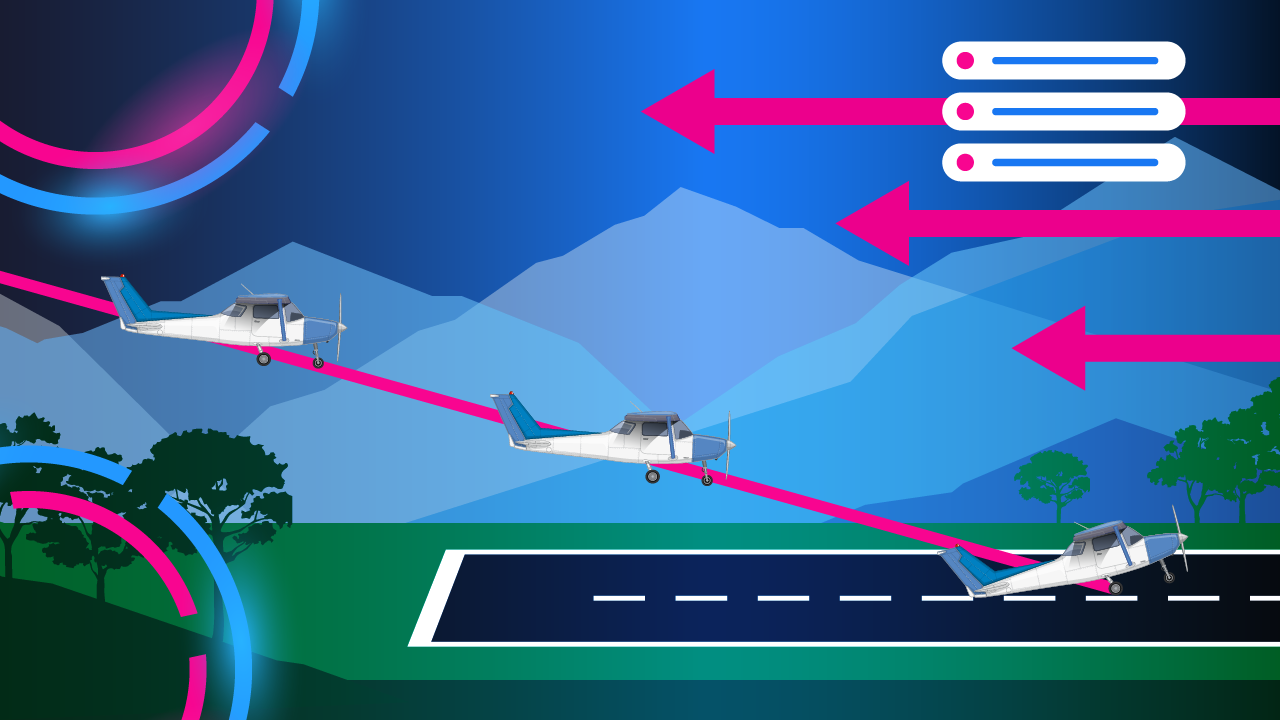

The roundout and touchdown is where everything changes.

On a normal landing, you’d pull the power over the threshold, begin your roundout, and flare around 10 feet AGL. The process is different for a soft field landing.

When crossing the threshold, start reducing the power. But, maintain around 200-300 RPM above idle (on smaller aircraft like the C172) to soften the sink rate. Hold this extra power as you enter ground effect.

Here is where your aircraft’s configuration comes into play. Low-wing aircraft perform better in ground effect because of the wing’s proximity to the ground. High-wing aircraft might need more power or pitch to arrest the descent.

Once you get within 5 ft of the surface, increase back pressure. Aim to keep the wheels about 1 to 2 feet off the ground and fly parallel to it while the aircraft decelerates. The aircraft will gently descend to the surface.

After you touch down, smoothly reduce your power to idle. Simultaneously, increase back pressure to keep the nose wheel off the ground. Make sure not to pull back too hard, or you could cause a tail strike.

Rollout

Maintain back pressure on the rollout. This does two things: it keeps the load on the wings and increases drag. The former prevents the wheels from sinking into the ground. The latter helps with aerodynamic braking.

The nose-high attitude of the aircraft might make it challenging to see the runway. A trick is to use your peripheral vision to keep the edges of the runway in sight to help with alignment.

The nose wheel will eventually touch as speed dissipates.

Using your brakes during a soft field landing is usually unnecessary. Soft surfaces have more friction and help slow the aircraft considerably. Heavy braking can cause the nose wheel to hit the soft surface too hard.

Similarly, do not reduce flaps. The sudden loss of lift can cause the wheels to dig into the ground.

Maintain back pressure and keep your taxi speed higher than usual until you move on to a harder surface. Slowing down too much can cause the aircraft to sink into the ground, making it difficult to move again.

Common Soft Field Landing Mistakes

Unstabilized Approach

A good landing starts with a good approach.

Continuing to land while unstabilized puts you dangerously behind the aircraft. If you fight for control all the way to the surface, there is little chance you’ll finesse the touchdown. This is particularly true of a soft field landing.

Being unstabilized means you’re not ready to land. Go around and try again. It is the safest and smartest decision.

Too Much Airspeed

Soft field runways tend to be shorter than paved runways. You don’t have the liberty of braking hard or rolling for hundreds of feet. Once you enter ground effect, too much speed will cause the aircraft to float or balloon.

Floating means you miss your touchdown spot, which can result in running out of runway. If the aircraft starts using up runway, a go-around is the prudent choice.

Ballooning can result in a stall and a hard landing, which can damage the gear and cause a nose-over.

High Descent Rate

If you have a high sink rate on approach, you’ll have a tough time arresting the descent during the roundout. This will likely result in a hard touchdown.

A hard landing is the least desirable outcome when attempting a soft field landing. The wheels might dig into the surface, increasing your chances of having an accident.

Overcorrecting for a high descent rate will cause the aircraft to balloon.

Not Adding Power If Needed

It is a common mistake not to add a little power during a soft field landing. After all, pilots become used to moving the power to idle when crossing the runway threshold.

But adding power in the roundout helps slow the descent rate, resulting in a smooth touchdown. So don’t be afraid to give the power a small bump during the roundout.

Releasing Backpressure on Touchdown

Usually, we want the aircraft’s weight on the landing gear to help with braking. But with a soft field landing, you want to maintain lift and keep the aircraft’s weight on the wings.

In addition, releasing backpressure will cause the nose wheel to touch down early. Letting the nose come down too quickly might result in the nose wheel sinking into the ground.

Stopping the Aircraft with Brakes

We want to keep the aircraft’s momentum going during a soft field landing. If we stop on the soft surface, we might get stuck and unable to move again.

Use the momentum from the landing and add power if necessary. Keep the aircraft’s speed up during taxi until you reach a hard surface.

Private Pilot and Commercial ACS Standards

Are you preparing for your Private or Commercial Pilot checkride? Let’s briefly cover the standards for soft field landings.

In both exams, you must keep the aircraft centered on the runway throughout the approach and landing, with minimal side drift. It’s okay if you’re pushed off the center by crosswinds as long as you recover.

If you’re unable to recover, make sure to go around. Your examiner will not fail you for good risk management and decision-making.

For a soft field landing, you must maintain the approach speed +10/-5 knots for PPL and +/-5 knots for CPL, plus any gust factor applied.

The ACS also highlights landing as close to your touchdown point as possible. However, unlike with a short-field approach, there isn’t a specified distance. Still, it’s good practice to land within short-field tolerances: 200 ft for PPL and 100 ft for CPL.

Conclusion

Soft field landings break some of the conventions of a normal landing. This is why pilots struggle with them. They have to unlearn some of the key lessons of normal and short-field landings. From adding power to not using brakes, it feels unnatural—at least at first.

However, the soft field landing technique is important to learn. And it’s not just a skill for pilots who fly out of grass strips. Should you ever need to make an off-airport emergency landing, you can rely on your soft-field mastery to get you through.Are you looking for more landing tips? Check out How to Perfect Your Airplane Landings.