-

Key Takeaways

-

Airplane Speed

- What Is Airplane Speed?

- How Airplane Speed Is Measured

-

Factors Affecting Airplane Speed

- Aircraft Design and Purpose

- Altitude and Atmospheric Conditions

- Weight and Load

-

Speeds of Different Types of Airplanes

- Commercial Airliners

- Private and Business Jets

- Military Aircraft

- General Aviation Aircraft

-

Airplane Speeds During Different Phases of Flight

- Takeoff

- Climb

- Cruise

- Descent and Landing

-

The Fastest Airplanes in the World

- Record-Holding Aircraft

- Supersonic and Hypersonic Flight

-

Limitations on Airplane Speed

- Regulatory and Safety Considerations

- How Speed Affects Flight Time and Efficiency

- Future of Airplane Speed

-

Conclusion

Imagine slicing through the sky at breathtaking speeds, the world below blurring into streaks of color. Some aircraft cruise at over 500 mph. Others are built to shatter the sound barrier itself.

What makes one airplane faster than another? The answer lies somewhere between purpose and physics.

Flying comes in different shapes. It can be a relaxed weekend flight in propeller-driven trainers or a sleek military jet built for raw speed.

Let’s talk about what drives and limits airplane speed, and how far human innovation is headed next.

Key Takeaways

- Airplane speed is how fast an aircraft moves through the air or over the ground.

- It’s measured in knots, Mach number, or miles per hour using pitot-static instruments.

- Factors like drag, weight, altitude, and engine power all influence how fast an airplane flies.

- Future developments focus on supersonic and hypersonic travel using advanced propulsion and aerodynamic innovations.

Airplane Speed

How fast does an airplane move? There’s more to it than just a single number.

The speed of airplanes can actually be described in many different ways. Each one tells us how the aircraft performs and how it interacts with both the air and the ground below.

What Is Airplane Speed?

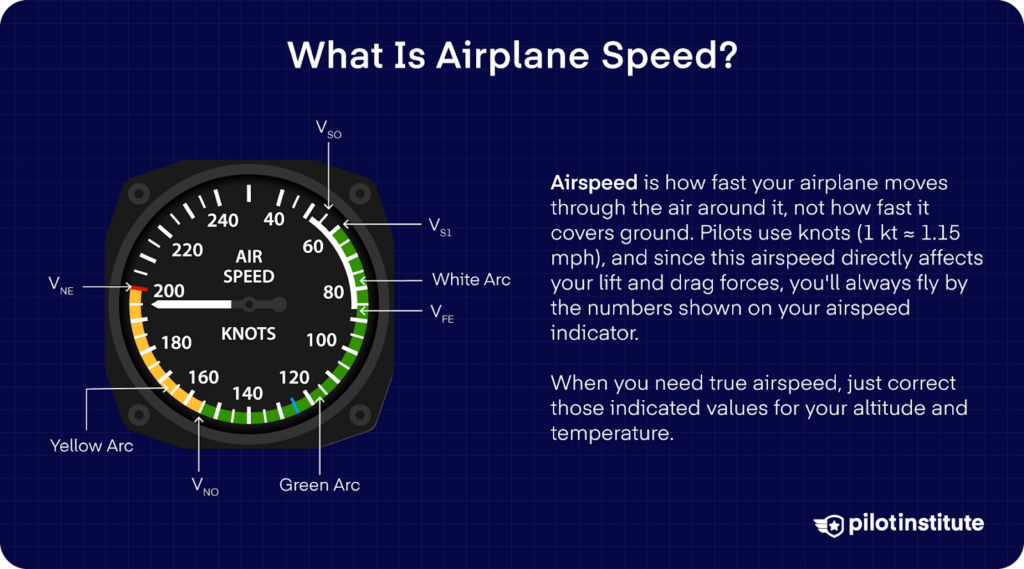

Two ways you’ll often hear airplane speed described are airspeed and ground speed.

Airspeed tells you how fast the airplane is moving through the air around it. Why does this matter? Airspeed is one of the factors that determine how much lift your airplane generates.

For example, an airplane traveling at 200 knots has four times the lift as the same airplane traveling at 100 knots (provided all other variables stay constant).

But when we talk about your aircraft’s actual speed over the ground, we use ground speed. It adjusts airspeed for wind. So, if there’s a tailwind, your ground speed increases; if there’s a headwind, it decreases.

Airspeed and ground speed are expressed in different units depending on the context. Pilots most commonly use knots, which measure nautical miles per hour. You may also see speeds given in miles per hour (mph) or kilometers per hour (km/h).

So you don’t get them mixed up, here’s a simple conversion guide:

- 1 knot = 1.15 mph

- 1 knot = 1.85 km/h

Then there are high-performance and jet aircraft that fly so fast and so close to the sound barrier that we need an entirely different scale to describe their speed.

It’s called the Mach number. It compares the aircraft’s true airspeed to the speed of sound under current atmospheric conditions.

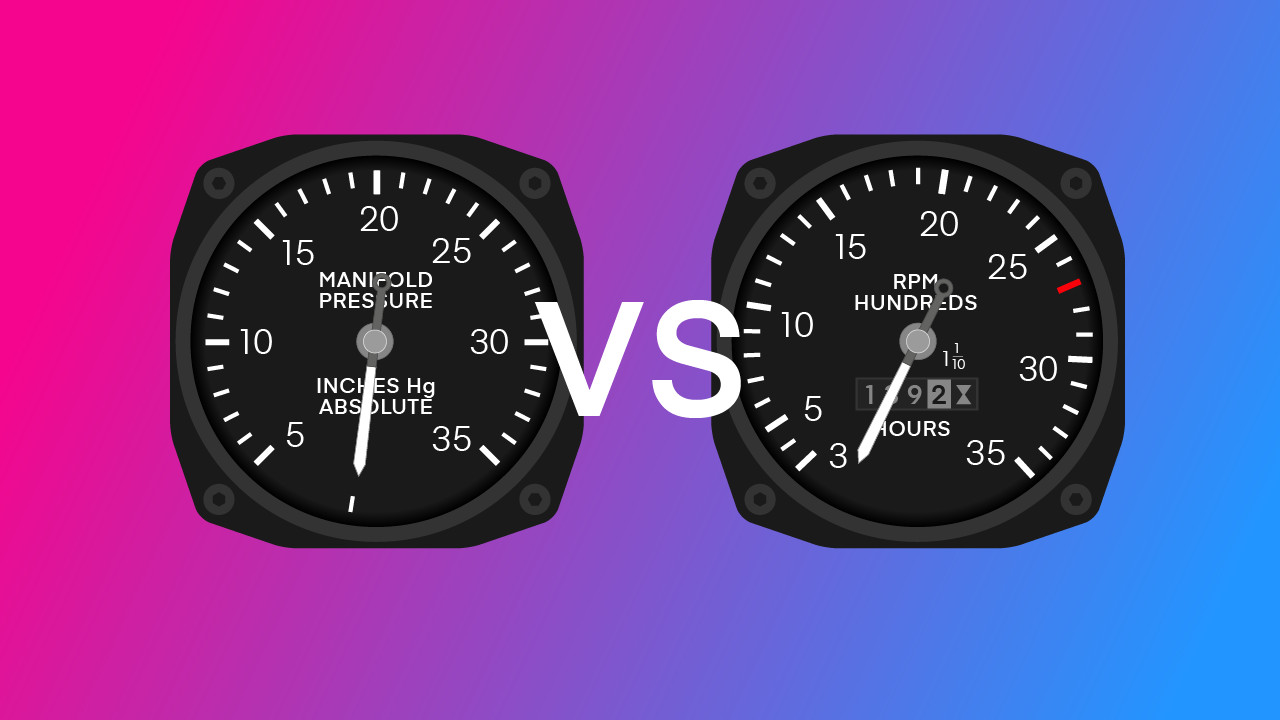

How Airplane Speed Is Measured

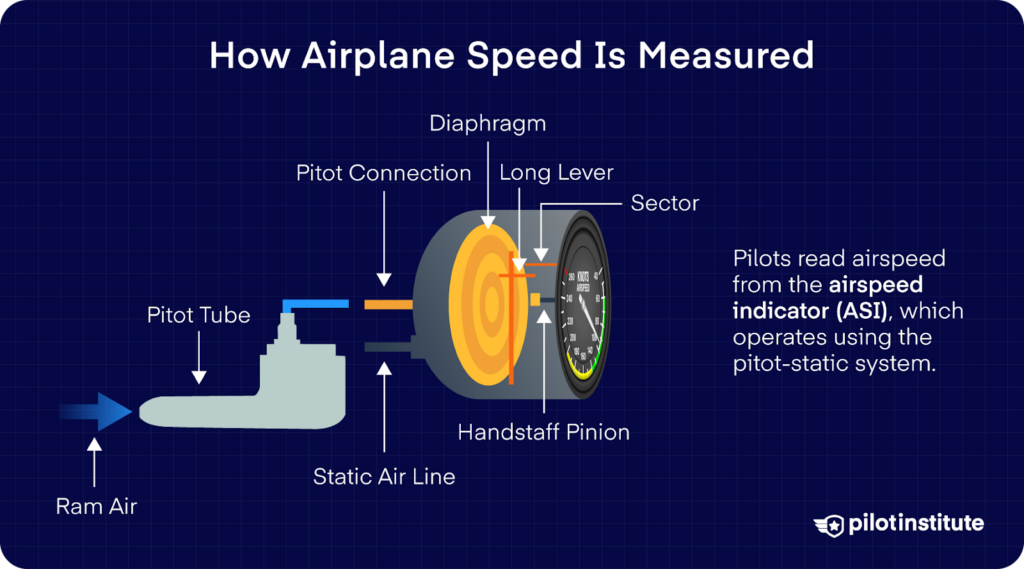

Pilots read airspeed from the airspeed indicator (ASI), which operates using the pitot-static system. So, how does it work?

The airspeed indicator receives inputs from both the pitot tube and the static port, which are separated by a diaphragm. The total pressure from the pitot tube is applied against the static pressure from the static port.

The resulting pressure on the diaphragm is the dynamic pressure. It’s pretty much doing a constant game of subtraction.

The diaphragm moves due to the pressure difference, which in turn moves the dial on the ASI. The final airspeed reading that the dial points to is the indicated airspeed (IAS).

However, this system isn’t entirely foolproof. Because of changes in altitude and temperature, the airspeed indicator won’t always be accurate.

For instance, at higher altitudes where air density decreases, the ASI may show a lower airspeed than is actually moving through your aircraft.

How can you get a more accurate measure of your airspeed? You can refer to the true airspeed (TAS). It’s your IAS corrected for altitude and non-standard temperature.

For high-speed flight, especially near or above the speed of sound, pilots rely on the Mach number. Remember that Mach number is the ratio of an aircraft’s true airspeed to the local speed of sound.

For example, an airplane flying at Mach 1.0 is moving at the speed of sound, while Mach 0.8 means it is traveling at 80% of that speed.

Why does this ratio matter? Well, as the aircraft approaches Mach 1, the airplane’s speed reaches (and could soon exceed) the speed of sound itself! Airflow over some parts of the surface reaches sonic speeds, and when this happens, shock waves form that can hurt handling and performance.

Factors Affecting Airplane Speed

Aircraft Design and Purpose

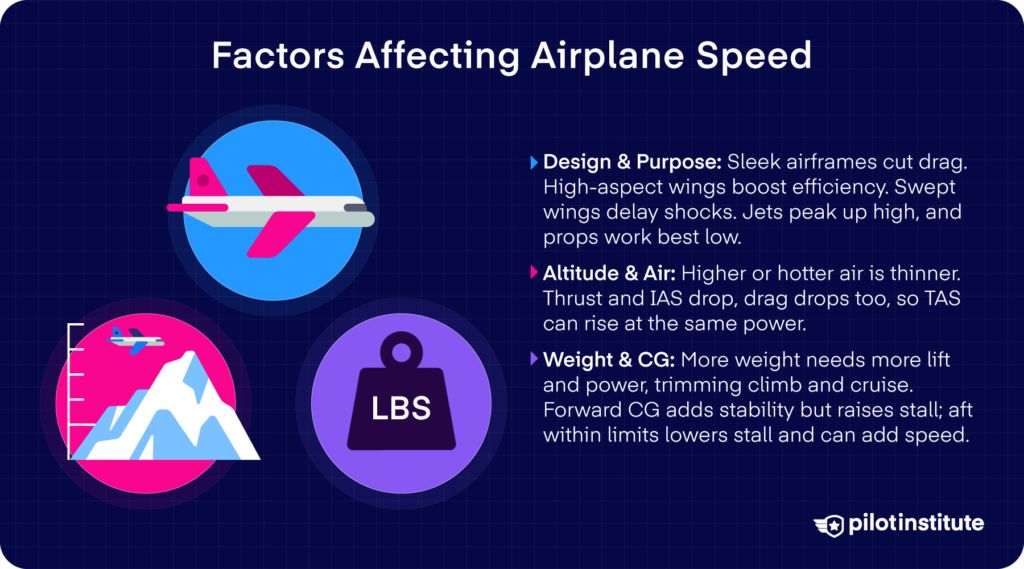

The design of an airplane affects how efficiently it moves through the air. Streamlined shapes and smooth surfaces reduce drag, which helps the aircraft fly faster with less resistance.

The wings also have an impact on speed. A high aspect ratio improves lift and efficiency, especially at high angles of attack. Sweepback wings, which are common in jets, help delay shock wave formation at higher speeds.

The type of engine installed determines how much thrust an airplane can produce. Turbojet or turbofan engines deliver higher speeds, suitable for both commercial and military use, because they can operate efficiently at high altitudes and in thinner air.

Propeller-driven aircraft, used mainly in general aviation, perform best at lower speeds and altitudes. Under these regimes, efficiency and control are easier to maintain.

Altitude and Atmospheric Conditions

Did you know that your altitude has a direct effect on your speed? That’s because as you climb higher, the air becomes thinner. The same goes for temperature. As it gets hotter, the air also becomes less dense.

When air density decreases, your propeller can’t generate as much thrust, and your airspeed suffers.

At the same time, though, the thinner air offers less drag. That means you can achieve a higher true airspeed at the same power setting.

Weight and Load

The weight of the aircraft affects how much lift it must generate to stay in the air. A heavier airplane requires more power and may not be able to climb or cruise as quickly.

Proper load distribution is also important. When the center of gravity is located forward (closer to the nose), the aircraft ends up being more stable, which is great from a control standpoint.

But on the flip side, you’ll see a slightly higher stall speed and a slightly slower cruising speed.

What if we move that weight aft, toward the tail? The aircraft becomes a bit less stable, but you’ll likely see a slightly lower stall speed and a slightly faster cruising speed.

Speeds of Different Types of Airplanes

Commercial Airliners

Commercial jets typically cruise in a range that balances speed with efficiency. You can fly fast to save time, but you’ll burn a lot of fuel doing it. Manufacturers decide the optimum cruise speed based on the type of routes they intend the aircraft to fly.

The Airbus A380 carries large passenger loads and typically cruises around Mach 0.85, at roughly 900 km/h.

Other large jets like the Boeing 747-8 fall into similar cruise-speed ranges, typically cruising near Mach 0.85. The Boeing 737 typically cruises around Mach 0.79, which is about 460 knots or 850 km/h.

The Boeing 787 Dreamliner also typically cruises at about Mach 0.85, around 488 knots (roughly 900 km/h), depending on the variant.

So overall, commercial airliners often cruise between about Mach 0.78 and Mach 0.85, which translates roughly to 450 to 490 knots (about 830 to 900 km/h), depending on altitude and model.

Private and Business Jets

Business jets are in a league of their own, where they emphasize both high speed and luxury. The Gulfstream G700 is a good example, and it’s got a maximum operating speed of Mach 0.935.

A speed demon in the bizjet world is the Bombardier Global Express, which can cruise near Mach 0.89 with long-range cruise speeds over 480 knots and a top speed just under Mach 0.90.

Another example is the Cessna Citation X+, which is known for being one of the fastest business jets in its category. It’s got a long-range cruising speed of 470 knots and a whopping maximum cruise speed of 528 knots!

Military Aircraft

Military aircraft are absolute beasts that are built for extreme performance, often exceeding the speed of sound. For example, cargo airplanes like the Boeing C-17 Globemaster and the Lockheed C-5 Galaxy cruise around Mach 0.75 (about 450 knots, or roughly 520 mph).

You’ll note that these are slightly slower than commercial jets. Their design focuses on payload capacity and short-field capabilities over outright speed.

The F-22 Raptor has declared cruise capability greater than Mach 1.5 without afterburner. What’s more, it can reach speeds over Mach 2 (around 1,500 mph) at higher altitudes.

Multi-role fighters like the F-35 and F/A-18E can fly at about Mach 1.6 (around 1,200 mph). Agile multirole fighters like the F-16 prioritize speed and maneuverability, so they can reach over Mach 2 (around 1,500 mph) at altitude.

Another example is the SR-71 Blackbird, which historically achieved speeds well over Mach 3! The Blackbirds were designed to cruise at about Mach 3.2, just over three times the speed of sound (around 2,100 miles per hour), and at altitudes up to 85,000 feet.

General Aviation Aircraft

In the realm of smaller, single-engine aircraft, their speeds tend to be much lower. Their focus is more on efficiency and practicality than maximum travel speed.

For example, the Cessna Skyhawk 172 has a maximum cruise speed of around 124 knots, or about 230 km/h.

The Cirrus SR22 has a maximum cruise speed around 183 knots, while the turbocharged SR22T can reach about 213 knots (roughly 394 km/h).

The Diamond DA40 sits between them, with a typical cruise speed around 145–150 KTAS (about 260 km/h), depending on model and power settings.

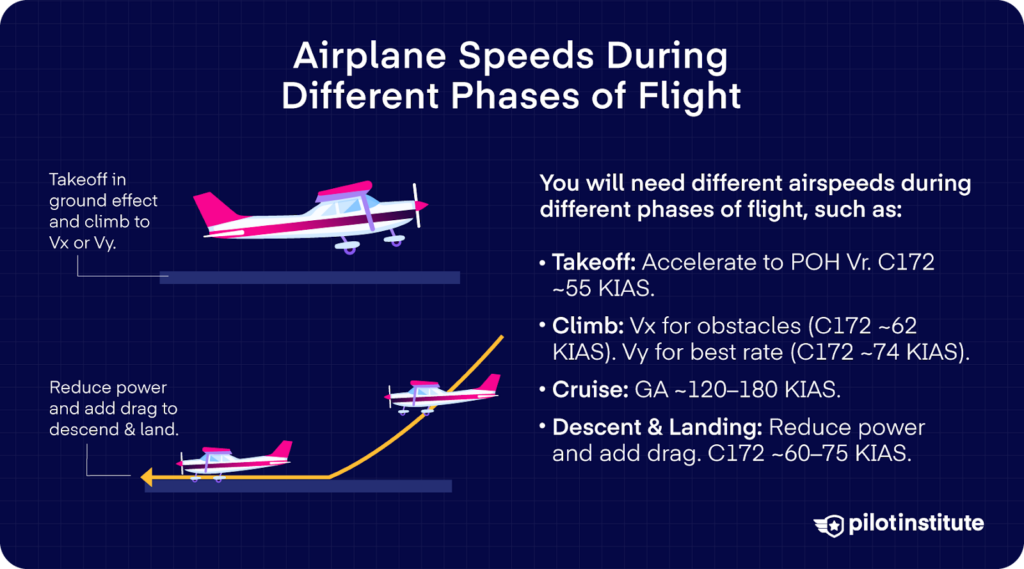

Airplane Speeds During Different Phases of Flight

Through every flight, there will be times when aircraft must slow down, and times when speed makes the most sense. When do these changes happen, and why? Let’s talk about it.

Takeoff

When it’s time to take off, you accelerate your aircraft down the runway until it generates enough lift to get airborne.

This speed depends on design and performance limits from the aircraft’s flight manual. Just to give you some examples, a Cessna 172 typically has a rotation speed of 55 knots. Jet aircraft like the Boeing 737 and the Airbus A320 leave the runway at around 145 knots.

But what if there’s not enough runway to accelerate, or you need to get airborne quickly? That’s where flaps come in to help.

When they’re extended, the flaps increase the camber of the wing, which helps the aircraft produce more lift at a lower airspeed. This lets you rise off the runway sooner and climb safely even when space or conditions are limited.

Climb

Once the aircraft is airborne, it continues to climb and usually accelerates to a more efficient airspeed. There’s a sweet spot that pilots target to balance performance and fuel burn, and it helps the aircraft gain altitude smoothly.

Do you want to get as high in as short a distance as possible? Or do you want to cut down on time?

If you need to gain altitude quickly over a short distance in a Cessna 172, you’d climb at about 62 knots (best angle of climb). If you want to gain altitude in the shortest time, you’d aim for about 74 knots (best rate of climb).

How about jet aircraft? Jets like the Boeing 737-800 and Airbus A320 typically climb at about 280–290 knots above 10,000 feet, then transition to a Mach climb around Mach 0.78.

Cruise

Once the aircraft reaches its cruising altitude, the speed levels off into a steady and efficient rhythm. The altitude helps because, since the air is thinner, there will also be less drag to slow you down.

Commercial airliners like the Boeing 737 and the Airbus A320 cruise at around Mach 0.79, which translates to about 450 to 460 knots true airspeed.

General aviation aircraft cruise much more slowly. A Cessna 172 cruises around 120 knots, while faster models like a Cirrus SR22 can cruise at about 180 knots true airspeed.

Descent and Landing

As the aircraft prepares to land, you break the speed gradually. Pilots lower the throttle and use drag devices like flaps and spoilers to help slow the aircraft down.

For commercial airliners, a typical descent keeps the aircraft near its cruise Mach number (around Mach 0.78–0.80) in the high flight levels, then switches to about 280–290 knots indicated down to 10,000 feet. Below 10,000 feet they slow to 250 knots or less, and by the final approach they’re usually around 130–150 knots depending on the aircraft and weight.

General aviation aircraft, such as the Cessna 172, typically fly final approach at about 65–70 KIAS with flaps up, and around 60–65 KIAS with flaps down.

The Fastest Airplanes in the World

Record-Holding Aircraft

Imagine flying faster than a bullet train. Now multiply that many times over, and you’ll still fall short of what some record-setters achieved. One of those legends is the Lockheed SR‑71 Blackbird.

It was designed to cruise at Mach 3.2, which is just over three times the speed of sound, or more than 2,200 mph, while flying at roughly 85,000 ft.

On 28 July 1976, one achieved an absolute certified speed of 1,905.81 knots (2,193.2 mph) in that class.

Then, there’s the experimental North American X‑15. It was a rocket-powered craft that literally pushed the envelope. The X-15 flew faster and higher than any other piloted, winged aircraft except the Space Shuttle.

On different flights, it reached speeds of Mach 6.70 (about 4,520 mph) and altitudes of 354,200 feet. While the program had the potential to break nearly every speed and altitude record, that wasn’t its purpose. Its true mission was to conduct research at hypersonic speeds and near-space conditions.

But if we’re talking about commercial aircraft, the Concorde was the fastest airliner ever to carry paying passengers.

How fast? The Concorde cruised at about Mach 2.02, which converts to roughly 2,179 km/h (1,354 mph). It became possible to fly from London to New York in just under three hours, thanks to its supersonic cruise. Its fastest one on record was completed in 2 hours, 52 minutes, 59 seconds.

Supersonic and Hypersonic Flight

What’s it like to fly faster than the speed of sound? Well, things start to get interesting.

You squeeze air so fast that shock waves form, airflow changes around the wings and fuselage, and special engineering is required.

Remember that the Mach number is the ratio of an aircraft’s true airspeed to the local speed of sound. When you break Mach 1, you change the game.

Supersonic flight sits roughly between Mach 1.2 and Mach 5. And while many military jets cruise in this region, they’re constantly subjected to structural stress and wave drag.

That moment in history when aircraft first exceeded Mach 1 was when everything changed. On 14 October 1947, Chuck Yeager piloted the Bell X‑1 to Mach 1.07. He became the first person to knowingly exceed the speed of sound in controlled level flight.

Go beyond Mach 5 and you reach the hypersonic regime. When you’re that fast, the materials used in typical aircraft, like aluminum and titanium, can warp, melt, or even vaporize completely!

As of today, hypersonic flight is still in development. But a couple of projects to look out for are the Lockheed Martin SR-72 and the Hermeus Quarterhorse Mk 1.

Limitations on Airplane Speed

When you imagine flying faster and farther, it’s tempting to think speed has no bounds. But in real-world aviation, many things limit how fast an aircraft can or should fly.

The drag that opposes motion grows as you increase airspeed. When drag equals thrust, the aircraft maintains constant speed, and to go faster, you must overcome more drag.

A reduction in drag also extends your aircraft’s range and lowers fuel consumption. If you ignore it, you’ll burn more fuel and potentially stress the aircraft beyond safe limits.

Flying faster means the aircraft’s structure must cope with greater aerodynamic loads and higher temperatures.

All of that puts a burden on your aircraft’s structure. The materials used and the design of the wings, fuselage, and control surfaces must all be able to handle these forces.

If the structure isn’t designed for higher speeds or you push beyond limits, you risk damage or failure. That’s also why engineers design maximum operating speeds to protect structural integrity.

Regulatory and Safety Considerations

And just like cars on the highway, aircraft also have speed limits set by the FAA. You’ll find them in 14 CFR 91.117. For example, when you’re flying below 10,000 feet MSL, you can’t exceed 250 knots unless you’ve been given special authorization.

This limit helps keep low-altitude airspace safer and gives everyone more time to react to other traffic or unexpected conditions.

The rules get even tighter if you’re closer to an airport. When operating at or below 2,500 feet above the surface and within four nautical miles of the main airport in Class C or D airspace, your airspeed should stay under 200 knots unless ATC requires or authorizes something different.

What’s the logic behind this limit? It helps controllers maintain smooth traffic flow near busy airports. However, this restriction doesn’t apply if you’re in Class B airspace. You’ll follow the 250-knot limit instead.

When flying underneath Class B airspace or through a VFR corridor that passes through it, you’ll also need to hold your speed below 200 knots.

These corridors are designed to let VFR traffic pass safely around major hubs, so keeping speeds manageable reduces risk and makes separation easier.

But what if your aircraft’s minimum safe airspeed happens to be higher than the limits set in these rules? Then you’re allowed to fly at that speed.

How Speed Affects Flight Time and Efficiency

Flying faster might get you to your destination in less time, but whether it saves you on fuel is a different story.

How come? If you go too fast, your engine might consume more fuel just to keep up. And if you go too slow, you’d just end up increasing time in the air and raising fuel burn in other ways.

That’s why every aircraft has an optimal speed for maximum range, and it’s not always the fastest it can fly. For instance, the Boeing 737 can cut its fuel burn by about 7% on a 500 NM flight simply by reducing its cruise Mach number from 0.78 to 0.74. And it would only add an extra 3 minutes to the block time.

Future of Airplane Speed

What does the future hold for aircraft speed? When it comes to supersonic passenger travel, one company is making headlines.

Boom Supersonic is developing the Overture, a supersonic airliner designed to cruise at Mach 1.7, reach 60,000 ft altitude, and cover 4,250 nautical miles with 60–80 passengers aboard.

Supersonic commercial flying seems to be making a comeback as United Airlines, American Airlines, and Japan Airlines have orders and pre‑orders of Overture to fly in their fleets.

Boom’s Overture aims to use 100% sustainable aviation fuel and a design that aims to subdue the ground-level sonic boom signature.

Hypersonic research takes things to the next level. Experimental projects are exploring aircraft speeds over Mach 5.

For example, the X‑43A achieved hypersonic speeds with scramjet propulsion. It shows potential for air-breathing engines beyond your typical jet.

Conclusion

The future of flight is racing toward something extraordinary. Each leap brings us closer to faster and cleaner travel.

Innovation is reshaping what’s possible, and it’s fueled by engineers, pilots, and dreamers who refuse to settle for limits. As technology advances, the next generation of aviators could redefine speed itself.

Stay curious and push forward. The sky isn’t the limit anymore, but just the beginning of where your journey in aviation can take you.