-

Key Takeaways

-

What Is Ditching?

- Common Causes of Ditching

- Ditching Procedures

-

Understanding Water Landings

- Unplanned Water Landings (Non-Emergency)

-

Main Differences Between Ditching and Water Landing

- Aircraft Design and Equipment

- Training and Certification

-

Ditching Procedures and Equipment

- Pre-Ditching Preparation

- Aircraft Ditching Equipment

- Importance of Training

-

Survival After Ditching

- Immediate Actions Post-Ditching

- Use of Survival Equipment

- Managing Environmental Challenges

- Factors Influencing Survival

-

Case Studies of Ditching

- US Airways Flight 1549 ("Miracle on the Hudson") – 2009

- Ethiopian Airlines Flight 961 – 1996

-

Importance of Understanding the Difference

- For Pilots

- For Passengers

-

Conclusion

As history has shown us pilots, engine failures can happen anytime. There’s no telling when they will happen, but when they do, we need to know how to respond.

Well, here’s a tricky scenario: what if it happens over an ocean or a lake? Do you know what to do? For pilots flying over water, knowing the difference between ditching and water landing can be a matter of life and death.

Let’s examine both concepts. Along the way, we’ll cover standard procedures and explain why they matter in emergencies and overall flight safety.

Key Takeaways

- Ditching is an unplanned emergency landing onto water when a runway is not available.

- A water landing is a planned descent onto water using aircraft designed for water operations.

- Survival involves emergency checklists, proper equipment, and a fast, coordinated evacuation.

- Knowing the difference will improve your preparedness, judgment, and chances of survival.

What Is Ditching?

Trouble can arise anytime in the air. In the worst cases, you might not have a runway or even solid land to land on. In a situation like this, your only option would be to ditch your aircraft.

Ditching is an unplanned emergency landing on water, and it’s something pilots do only when a runway just isn’t within reach.

Unlike water landings in specially equipped aircraft, ditching usually happens in airplanes not built for water touchdowns, so you have to act quickly and precisely.

But since your aircraft won’t be in its element, keep in mind that ditching is your absolute last resort during an in-flight emergency.

“The Ditch”

Have you ever wondered where the term “ditching” came from? “The ditch” actually used to be a slang term the Royal Air Force used to refer to the English Channel.

When a land-based aircraft had to make a water landing, they described it as “ditching.” The phrase caught on, and eventually, it became used in formal aviation jargon.

Common Causes of Ditching

Ditching can result from several dire situations over water. One major cause is engine failure, which may be caused by mechanical trouble or running out of fuel.

You can also lose control due to severe weather, sudden mechanical issues, or external hits. One infamous example is a bird strike, like what happened on the Miracle on the Hudson, US Airways Flight 1549.

But ditching is not just a matter of engine trouble, either. Onboard fires or structural damage can force an immediate decision to ditch just for the sake of safety.

Ditching Procedures

When ditching becomes inevitable, safety all hinges on your next steps. How can you guarantee your survival? Here’s what you can do:

- Mayday call. First, broadcast a Mayday to alert air traffic control and kick off search-and-rescue efforts.

- Prepare cabin and passengers. Then comes the cabin briefing. Passengers must be coached into brace positions and shown how to use life jackets.

- Secure the aircraft. Your aircraft has a checklist for ditching. Follow the steps down to a T: seal the vents, lock up the landing gear (usually by retracting put-away gear), and make sure everything is as water-tight as possible.

- Controlled descent and touchdown. Survey the water and choose the smoothest stretch. Slow the aircraft to just above stall speed, and keep a nose‑high attitude.

Understanding Water Landings

Now, on the flipside, if you fly a seaplane or amphibious airplane, water landings are just another part of the mission.

These aircraft come equipped with floats or a hull specifically designed for water operations. They’re used in passenger service, recreation, and access to remote destinations.

Do you want to try your hand at water landings? You’ll first have to go through specialized training and follow routines whenever you take off or touch down on water.

Your flight school should cover things like choosing a proper landing path, scanning for obstacles, and managing water conditions. The FAA Seaplane, Skiplane, and Float/Ski Equipped Aircraft Handbook spells out these procedures so you can read up before you start your training.

Unplanned Water Landings (Non-Emergency)

Not all water landings are emergencies. In fact, you might intentionally land on water during demonstration flights or training missions.

These are planned and controlled. You pick the location, the water’s calm, and the aircraft’s ready. You’re flying something built for this purpose. It’s not an emergency but just another part of the job.

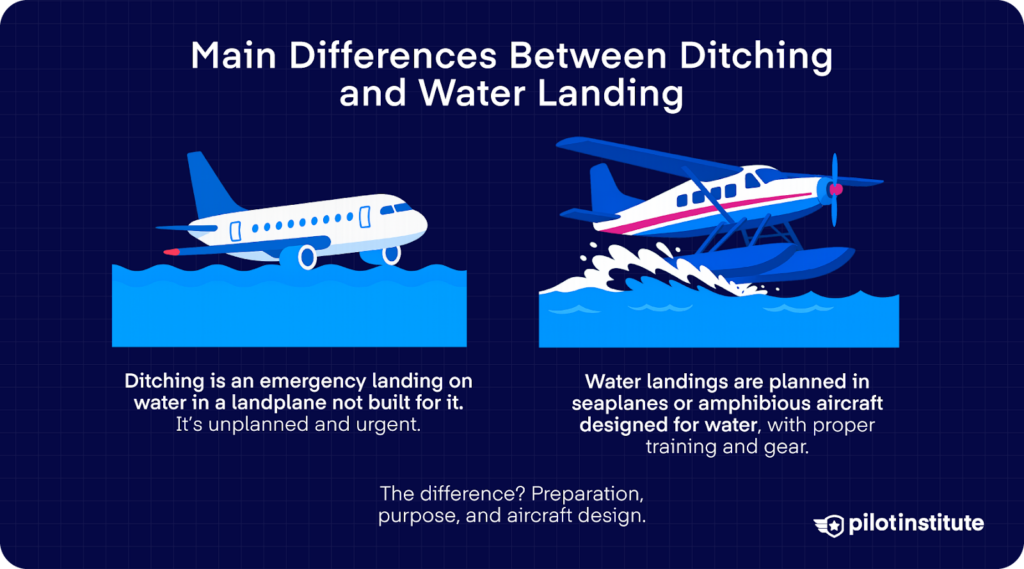

Main Differences Between Ditching and Water Landing

When you break it down, ditching and water landing couldn’t be more different, even though both end up in water.

Ditching comes out of nowhere. It’s an unplanned emergency that forces you into action with little time to prepare. As your aircraft falls, every second counts.

On the other hand, water landings are planned and done on purpose. They’re performed under controlled conditions where everything in your aircraft and your landing field is set up ahead of time.

Aircraft Design and Equipment

The differences also come down to the equipment your aircraft has. With ditching, you’re flying a landplane not designed for water. It lacks the equipment needed to land safely on water. Instead, you’re relying on emergency gear like life jackets and rafts in case things go sideways.

By contrast, water landings happen in seaplanes or amphibious aircraft. These rely on floats, hulls, and skis, complete with watertight compartments to land and float safely.

You’re operating an airplane equipped to handle water, not hoping your aircraft comes with a life raft.

Training and Certification

How can you know how to handle both? If you’re preparing for ditching, you’ll get basic emergency training, often as part of overwater flight preparations. You’ll be studying survival skills and ditching checklists.

But for water landings, you need the specialized seaplane rating and must train extensively on water operations. You learn how to manage floats or hulls and maneuver in water.

All of your actions must follow strict regulatory procedures laid out in the FAA seaplane handbook. It’s comprehensive training that goes far beyond basic overwater survival drills.

Ditching Procedures and Equipment

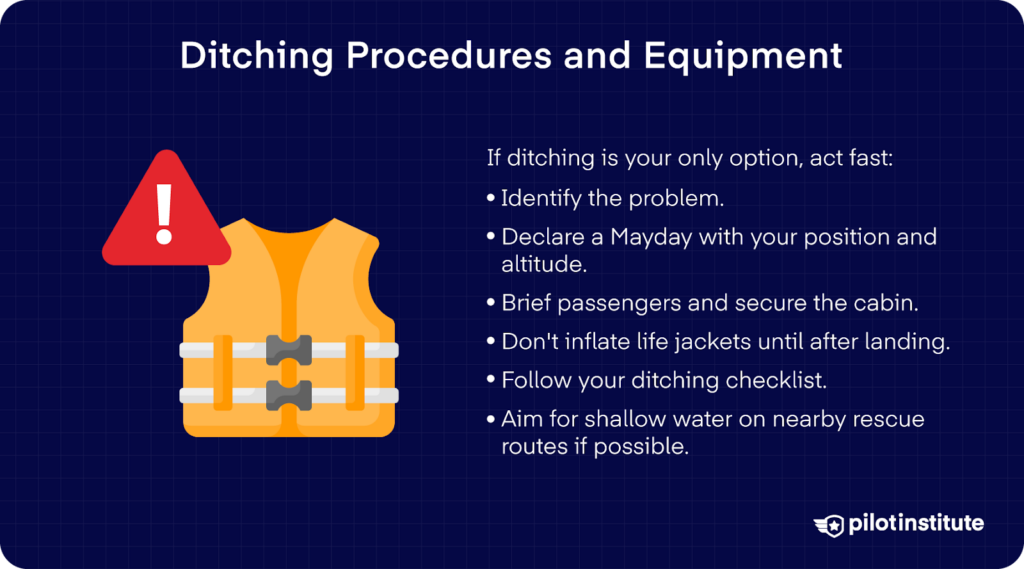

So let’s say an emergency happens in flight, and you look around to see only water below. You’re left with no choice but to ditch; what do you do next?

Pre-Ditching Preparation

When you realize a ditching is imminent, there’s no time to waste. You need to assess the situation fast. Are you having engine or control trouble? Perhaps you’ve run out of fuel? Nail down the issue, then get moving.

Declare the Emergency

First, you contact air traffic control or flight service with a Mayday call. Be concise. You have to state your callsign, position, altitude, and the nature of the emergency. That lets search and rescue begin gearing up.

Secure Passengers and Cabin

Then, you shift focus to the cabin. You or the cabin crew should instruct passengers into brace positions.

Have them buckle up and put on life jackets, but do not inflate the jackets just yet! Otherwise, they’ll block the exits during evacuation. Any and all secure loose items must also be stowed so nothing turns into a projectile on impact.

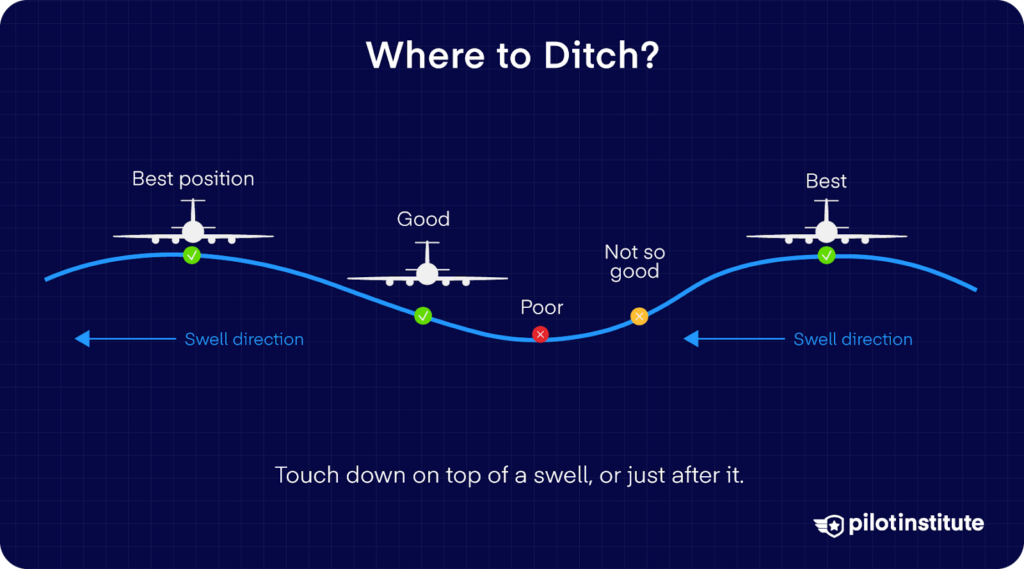

Where to Ditch?

Once everything is secure, it’s time to prepare the aircraft for the ditch. Follow the ditching checklist as described in the POH/AFM of your aircraft, if it has one.

But just because it’s all water below doesn’t mean you can just ditch anywhere in any configuration. So, what’s the best way to make your approach?

If possible, aim for shallow water. You should glide towards a beach, a ship, or along a shipping lane to improve your chances of rescue.

Ideally, if the water is smooth or has a long, smooth swell, then you should aim to land into the wind. But if you’re facing large swells or a rough sea, it’s safer to land along the swell, even if that means accepting a crosswind. This reduces the risk of your aircraft’s nose digging into a wave.

Remember that waves usually move with the wind, except near shorelines or fast-moving estuaries. Swells, however, can move in any direction and may have little to do with the surface wind.

Aircraft Configuration

A well-executed ditching or water landing is usually less jarring than crashing into trees or landing on rough terrain, although this is still a debate among pilots.

If your engine is still running, use it to make a powered approach when ditching. Having power gives you much better control over where you touch down, so try not to run out of fuel before you’re ready.

From high up, water often looks calmer than it really is, so fly low first and take a good look at the surface before you commit.

Another thing to watch out for is the loss of depth perception over smooth, wide water. It can trick you into flying straight into the water or stalling too high.

To avoid that, the airplane should be “dragged in” when possible. If you’re flying a low-wing aircraft, stick to intermediate flaps. Also, keep the landing gear up unless your AFM or POH tells you otherwise.

Touchdown and Evacuation

When it’s time to land, aim for the slowest flying speed you can manage without stalling. If you ditch at minimum speed and keep the aircraft in a normal landing attitude, it likely won’t sink right away.

In fact, intact wings and empty fuel tanks can keep you afloat for several minutes.

Be ready for a double impact during ditching. You’ll feel the first when the tail hits the water, followed by a stronger second jolt when the nose makes contact. The aircraft might also veer to one side on impact.

Aircraft Ditching Equipment

When you’re planning for a water emergency, the right gear aboard your aircraft can make all the difference. With the equipment you have at your disposal, how can you make the most of them?

For certain operations, such as extended overwater flights in transport category aircraft, the FAA requires specific equipment. This includes an approved flotation device (like a life jacket) for each occupant and enough approved life rafts to accommodate everyone on board.

Requirements for general aviation aircraft vary based on the type of operation and are outlined in regulations such as Part 91.

ELTs are designed to activate automatically. Upon impact, they should send a distress signal that helps rescuers find you.

Importance of Training

But even with all the right gear, your best tool in a ditching is your training. Regular emergency drills will help you and your crew become familiar with how to use the flotation gear.

Cabin drills ensure that everyone knows their roles. Coordinated responses mean you’re not scrambling at the moment. Practice them both on land and water so you’re ready for any challenge.

Survival After Ditching

So you’ve stuck the landing–or the ditching, and everyone has made it alive. What do you do next?

With water slowly flowing into your aircraft, there is no time to waste. But don’t panic; survival is very possible as long as you take your next steps properly.

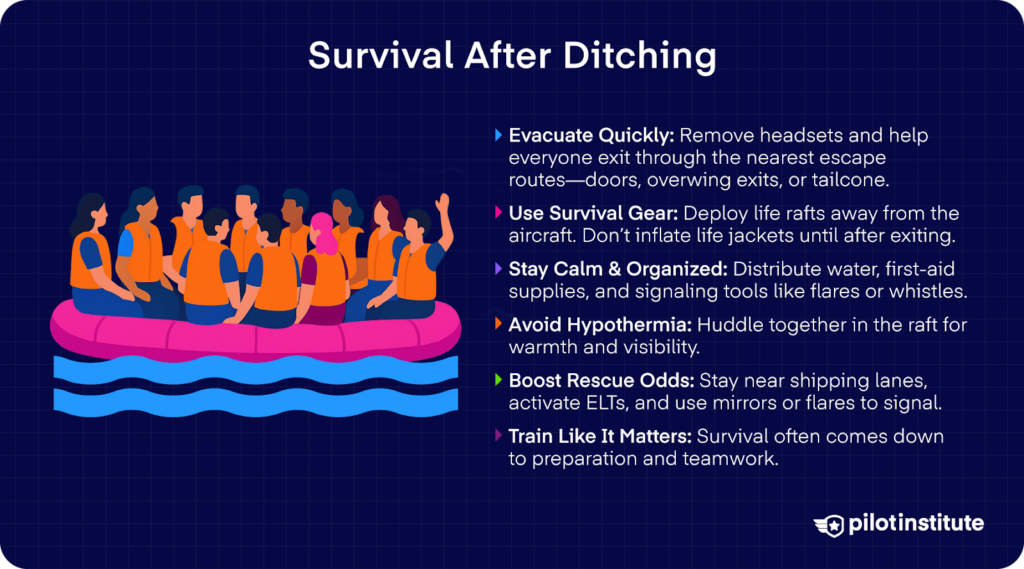

Immediate Actions Post-Ditching

Once you’ve landed on the water, your top priority is getting everyone to safety. First, you must help your passengers and crew find their way out.

Remove headsets and anything else that may get in the way during the evacuation. Take charge and direct your passengers to the nearest escape routes.

Are you familiar with the ones in your aircraft? You can evacuate through the doors, ventral exits, or the tailcone. If your aircraft has them, you can even use slides or overwing exits.

On many airliners like the A320, the overwing exit hatches are designed to be completely removed. The critical component is the slide. Overwing slides are often not detachable and cannot be used as rafts, unlike the slide-rafts at the main doors.

Use of Survival Equipment

Your aircraft is designed to float for a long enough time for everyone to evacuate and get onto the liferafts. While this is happening, you should emphasize staying calm to avoid delays or any more injuries.

Afterwards, deploy the life rafts away from the sinking fuselage. Help your passengers board and keep the atmosphere as stable and controlled as possible.

Once they’ve made their way out, only then can your passengers inflate their life jackets.

Next, it’s time to tap into survival gear: distribute water, first‑aid supplies, and signaling tools. Use locator transmitters (ELTs) already activated on impact. You should also hand out extras like flares, mirrors, or whistles to boost your chances of being spotted by rescuers.

Managing Environmental Challenges

Once outside, your biggest threats will be cold water and exposure. How can everyone stay warm? Coach everyone to huddle and share body heat in the raft. A simple act like this is a lifesaver; it will help stave off hypothermia.

Forming a large huddle will also make you more visible to rescuers. But more than that, it’s a source of emotional support in a very frightening situation.

Factors Influencing Survival

Many variables can make a difference in how well you and your passengers fare after ditching.

First, there’s your environment. Cold, rough waters dramatically increase the risk of hypothermia and drowning, while calmer, warmer conditions improve your chances.

Next, a rapid rescue response is absolutely vital. How can you signal for help? A strong ELT signal, along with visible flares or mirrors, can make a big difference in getting noticed quickly.

Staying close to rescue resources like ships or shipping lanes can also cut down your time in the water.

Lastly, preparation and training matter more than you might expect. When you and your crew are well-practiced in evacuation procedures, everything runs more smoothly.

It dramatically improves how quickly and efficiently you can get everyone out. It also keeps the team coordinated under pressure.

Did you know that drowning remains the leading cause of post-ditching fatalities? This means survival comes down to how efficiently crews and passengers work together.

Case Studies of Ditching

When it comes to ditching, the past reminds us: it can go either way.

Some crews have made textbook ditchings and walked away to become aviation legends. But for others who faced the same split-second decisions, they weren’t as lucky.

US Airways Flight 1549 (“Miracle on the Hudson”) – 2009

Right after take-off from LaGuardia, US Airways Flight 1549 encountered a flock of Canadian geese. The birds entered the fan and core sections of each engine, resulting in a near-total loss of thrust.

With the Airbus A320 rapidly falling and LaGuardia five miles away, Captain “Sully” Sullenberger declared, “My aircraft.” His decision? Aim for the Hudson River.

In less than four minutes, he flew the aircraft into the water in a controlled descent. Once the aircraft touched down, crew coordination took over. There was more work to be done.

Sully and First Officer Jeffrey Skiles kept things calm and focused, while the cabin crew led an orderly evacuation via slides and overwing exits. Nearby ferries, along with the Coast Guard and NYPD, arrived within minutes to pull all 155 people to safety.

Thanks to swift decision-making and procedures done smoothly, everyone survived with only 5 severe injuries and 95 minor injuries. It’s now regarded as one of the most successful ditchings in history. But more than that, Flight 1549 reshaped training and safety protocols for aviation in the future.

Ethiopian Airlines Flight 961 – 1996

On November 23, 1996, Ethiopian Airlines Flight 961 was hijacked just 20 minutes after departing Addis Ababa. Three kidnappers stormed the cockpit of the Boeing 767 and demanded that the aircraft be flown to Australia.

The other problem, though, was that the aircraft didn’t have enough fuel for such a journey.

Captain Leul Abate tried to reason with them. He pointed out that they’d only fueled for a few hours, but the hijackers insisted. As fuel ran dangerously low, the hijackers continued to interfere. They vied for control and prevented a proper landing.

Then, at just 500 yards off Grande Comore’s coast, both engines failed.

The captain performed a forced ditching onto shallow water, and even tried to align parallel to the waves. But seconds before touchdown, the left wingtip clipped a coral reef. The impact caused the aircraft to yaw violently and break apart.

Tragically, 125 of the 175 onboard perished. Some passengers are also thought to have drowned after inflating life jackets inside the cabin and became trapped.

For us pilots, Flight 961 is a tough reminder of three important elements in ditching:

- Control of the cockpit.

- Environmental awareness.

- Crew coordination.

Importance of Understanding the Difference

For Pilots

From what we’ve seen, there are important distinctions between ditching and water landing. Why should we know the difference?

As a pilot, it will sharpen your decision-making skills during overwater emergencies. You’ll have better judgment when a ditching is truly unavoidable.

You’ll also be more prepared for ditching when you understand the protocols. Along with this comes a mastery of the different requirements set by the FAA, like carrying life jackets and rafts.

But perhaps most importantly, knowing the difference will give you motivation to practice emergency drills regularly. They will strengthen your decision-making and the coordination of the crew, so that everyone can act instantly even under stress.

For Passengers

Passengers benefit from this knowledge, too. Awareness of the difference helps them appreciate safety briefings. They’ll be more encouraged to pay attention to the exit routes and how to use their life jackets.

When passengers know how to assist in their own evacuation, they become active participants in safety. This effort will greatly impact everyone’s collective chance of surviving an emergency.

Conclusion

Ditching and water landings may both involve water, but that’s where their similarities end.

Ditching is an unplanned emergency where every second counts. And oftentimes, it involves an aircraft that is not built for water.

Water landings, on the other hand, are planned operations. They’re for aircraft with specialized equipment flown by trained and rated pilots.

If you’re a pilot, keep sharpening your skills. Know your aircraft, run the checklists, and rehearse your emergency responses.

If you’re a passenger, don’t tune out the safety briefing. Those few minutes of attention can save your life.

In aviation, preparation simply isn’t optional, and this goes for every situation in the cockpit. Know the difference and train like it matters. Because one day, it just might.