-

Key Takeaways

-

What Is a Deadstick Landing?

- Why It's Called “Deadstick”

-

How Pilots Handle Engine-Out Emergencies

- Basic Safety Concepts

- Engine Failure After Takeoff (Single-Engine)

-

Can Large Aircraft Perform Deadstick Landings?

- The Gimli Glider

-

Practicing Deadstick Landings

- The Importance of Scenario-Based Training

- Handling Engine Failures in Multi-Engine Aircraft

- The Role of Flight Simulators

-

Differences Between Deadstick Landings and Normal Landings

- Approach Control

- Glide Ratio

- Pilot Training: Preparing for No-Power Landings

- Risk Factors

-

Other Types of Landings

- Emergency / Abnormal

- Technique / Performance

- Ops / Procedure

- Water Clarifier

-

Conclusion

In July 1983, Air Canada Flight 143 was flying from Ottawa to Edmonton when the Boeing’s left engine quit halfway through the flight. The pilots decided to make an emergency landing in Winnipeg until, just moments later, the right engine also gave out.

The aircraft had run out of fuel and was gliding without power from 35,000 feet.

If you were the pilot in the cockpit, what would you do?

This scenario is known as a deadstick landing, where a pilot must land an aircraft without engine power.

In this article, we’ll explore how pilots handle engine failures, FAA procedures for emergency landings, and how deadstick landings compare to routine operations.

And later on, we’ll find out what happened the fateful flight of Air Canada Flight 143.

Key Takeaways

- Deadstick landings require pilots to glide and land without engine power.

- Training prepares pilots to handle engine-out emergencies.

- FAA standards emphasize practicing no-power landings for safety reasons.

- Glide control and approach management are life-saving without engine thrust.

What Is a Deadstick Landing?

A deadstick landing is an emergency landing performed without engine power. When your aircraft loses thrust, you’ll have to glide it safely to the ground using only aerodynamic control.

There can be many reasons why you’d have to make a deadstick landing. It can be caused by an engine failure, fuel exhaustion, or mechanical issues.

But unlike in a normal landing, where you can fine-tune the approach with power adjustments, a deadstick landing requires precise energy management.

Training for deadstick landing includes understanding the best glide speeds and identifying safe landing zones to make a smooth touchdown.

In pilot certification programs, simulated engine-out landings are a routine part of training. The FAA requires pilots to practice power-off approaches to ensure they can handle real-world emergencies.

Why It’s Called “Deadstick”

But why is it called a deadstick landing? The term originates from early aviation, and it refers to the aircraft’s wooden propeller.

When the engine is running, the propeller is in motion, actively generating thrust. However, when the engine fails, the propeller stops spinning and becomes a dead stick. The name has stuck ever since, even as aircraft technology has evolved.

And to clarify, if the pilot decides to land as a precautionary measure, even with engine power, it’s called a precautionary landing, not a deadstick landing.

How Pilots Handle Engine-Out Emergencies

Surviving a forced landing isn’t just about skill; it’s about making the right choices. What should you do if the engine fails just after takeoff?

Basic Safety Concepts

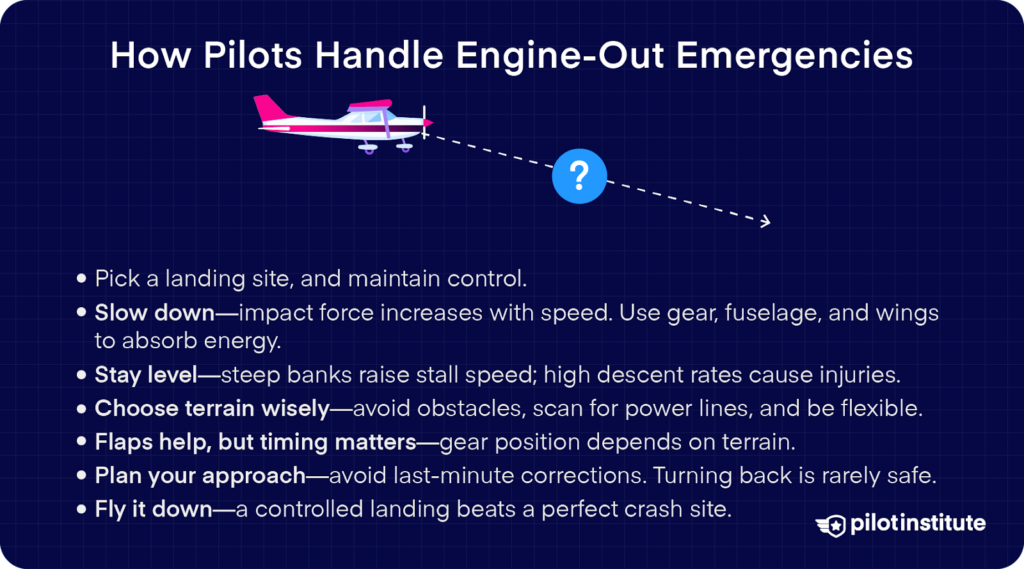

Without engine power, every tiny decision can decide your landing’s outcome. The FAA recommends these basic safety principles to maximize your chances of a safe touchdown.

Energy Management

One of the most important principles is energy management. You should keep the cabin intact, which could mean sacrificing other structures to absorb impact forces.

You can rely on the landing gear, fuselage bottom, and wings to take the brunt of a crash while keeping you and your passengers safe inside the cabin.

But perhaps the most critical factor is your speed. Do you know why? Doubling your groundspeed quadruples the impact force.

The safest touchdown happens at the lowest controllable airspeed, and you’ll be using aerodynamic devices to slow down.

While you might want to go for large open fields, stopping distance matters less if your deceleration is uniform. Aircraft carriers use this concept with arresting gear for controlled stops.

Although light airplanes are designed to withstand crash forces up to 9G, keep in mind that higher speeds add up to the stopping distance.

Attitude and Sink Rate Control

Another important factor is controlling attitude and sink rate. A nose-low touchdown on flat terrain could dig the nose into the ground. On the other end, with a steep bank angle, you could increase stall speed and the chance of a wingtip strike.

Since vertical velocity drops to zero at touchdown, it’s important to keep on top of your sink rate. A hard, flat landing at a high descent rate can still cause injury, even if the cabin remains intact. Keep a controlled descent and a level attitude to avoid any structural damage or injury.

Terrain Selection

Where do you plan to touch down? While of course, a runway is ideal, even rough terrain can be survivable if approached correctly.

Terrain appearances can be very misleading, and you may already lose some altitude before you pinpoint a landing spot. And if a safer landing spot appears up close, don’t hesitate to discard your original plan.

As a general rule, though, you shouldn’t change your mind more than once. You’d much rather have a well-executed crash landing in poor terrain over an uncontrolled touchdown on an established field.

Once you’ve determined your touchdown point, it’s better to force the aircraft down on the ground than to delay touchdown until it stalls. Yes, even if the open space is limited.

A river or creek can be a great plan B; just make sure that you can make it without snagging the wings. This also applies to road landings with one extra reason: you might not see manmade obstacles until the final portion of your approach.

Most highways–even rural dirt roads–are paralleled by power or telephone lines. Only a sharp lookout for the supporting structures could give you a timely warning.

But let’s imagine the worst-case scenario, where you can only land in trees. What should you do?

According to the FAA, you should first use full flaps with the gear down. Then, head into the wind to reduce groundspeed and “hang” the airplane in the branches in a nose-high attitude.

The first contact with the trees should be on the fuselage and both wings. This will give you a positive cushioning effect and prevent branches from breaking into your windshield.

You should avoid direct contact with heavy tree trunks. But if it can’t be helped, it’s best to involve both wings simultaneously between two properly spaced trees. And if you’re still airborne, never try to do this maneuver.

Aircraft Configuration

How should you configure your aircraft for a dead stick landing? You can use flaps since they improve maneuverability and reduce stall speed. But if you use them too early, your glide distance might come up short.

Landing gear position also depends on the terrain. In rough areas, extended gear can protect the cabin. In soft fields, a gear-up landing might reduce damage.

However, you should always follow manufacturer guidelines. If time allows, deactivate electrical systems before touchdown to minimize fire risk.

Approach

Approach planning can feel like a balancing act between wind direction, field dimensions, and obstacles. Since these factors rarely align perfectly, the safest call is to prioritize an unobstructed final approach.

Overestimating glide range can lead to dangerous last-minute maneuvers, so it’s better to clear obstacles early, even if it means letting go of a potential headwind. Careful planning guarantees you a controlled, survivable landing.

Engine Failure After Takeoff (Single-Engine)

An engine failure just after takeoff is one of the most dangerous situations a pilot can face. You have little time to react, and your altitude is often too low for a safe turn back to the runway.

So, what should you do?

- Lower the nose immediately. Your natural reaction might be to pull back, but your top priority should be to maintain airspeed. A stall at a low altitude is almost always fatal.

- Pick a landing site ahead. If the aircraft is below 1,000 feet, turning back is usually impossible. You are trained to land straight ahead or slightly to the side.

- Maintain control. A controlled crash landing is far better than losing control. Focus on keeping the wings level and touching down as gently as possible.

- Avoid obstacles. If possible, aim for open areas and avoid power lines, buildings, and traffic.

Turning back to the runway—often called the impossible turn—is rarely a safe option. A 180-degree turn at a low altitude takes up a lot of altitude you’ll have to sacrifice. Any small error or miscalculation could end up in a crash.

Those who attempted it often stalled and crashed before reaching the airport. That’s why the FAA strongly advises against it unless a pilot has mastered their skills and their aircraft’s performance.

Can Large Aircraft Perform Deadstick Landings?

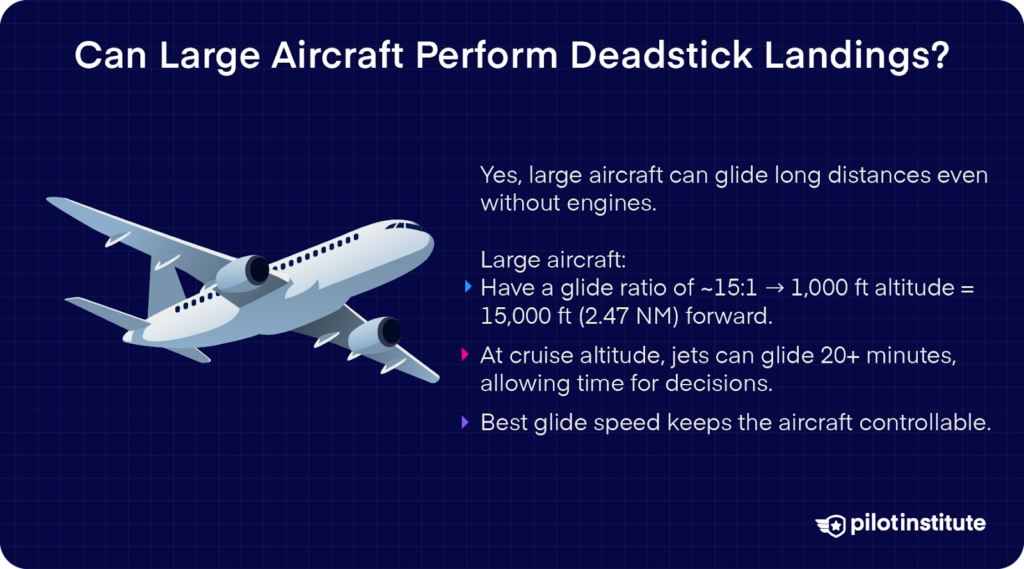

Can a massive commercial jet, like a Boeing, glide safely if all its engines fail? Seems unlikely, but yes, it can.

Large aircraft have exceptional glide capabilities. They can fly great distances even without engine power. But even so, successfully landing a commercial jet in a deadstick scenario takes skill and quick decision-making.

Aircraft glide ratio plays a huge role in engine-out situations. Most commercial jets have a glide ratio of around 15:1, meaning that for every 1,000 feet of altitude, they can glide roughly 15,000 feet (2.47 nautical miles) forward.

This gives you a lot of precious time at cruising altitude—often 20 minutes or more. You can troubleshoot, communicate with air traffic control, and find a suitable landing site.

While jets can’t sustain flight indefinitely without power, they don’t simply fall from the sky. Instead, you can follow best glide speed procedures to stay in control.

The Gimli Glider

One of the most famous cases of a dead stick landing is Air Canada Flight 143. The Boeing 767 ran out of fuel mid-flight because of a fuel miscalculation. Both engines quit, the aircraft lost all thrust, and the 767 became an enormous glider.

Captain Robert Pearson and First Officer Maurice Quintal looked at their options and determined that an abandoned airstrip turned racetrack in Gimli, Manitoba, was within reach.

It was a tough situation. They were managing altitude, controlling descent, and attempting a safe landing—all without engine power.

So, what happened? Well, Captain Pearson and First Officer Quintal successfully performed a deadstick landing. They touched down over the racetrack in Gimli Motorsports Park, and all 69 occupants survived without any major injuries.

The flight soon became an aviation legend and has since been known as “The Gimli Glider.”

This landing was anything but routine. Despite the challenges, the pilots successfully landed the aircraft and avoided disaster.

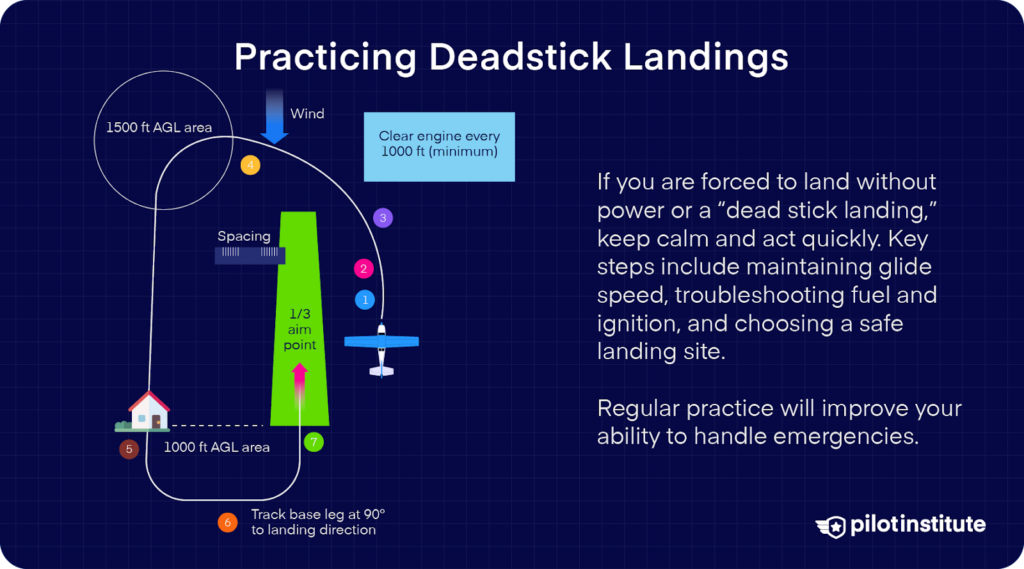

Practicing Deadstick Landings

So, how can you train to land an aircraft without engine power? Engine failures and inflight emergencies often happen when you least expect them, which is why preparation and training are highly essential.

The Importance of Scenario-Based Training

Emergencies require more than just memorized procedures. They demand real-world problem-solving skills. The FAA highlights SBT as an effective method to prepare pilots for inflight emergencies.

Instead of learning procedures in isolation, SBT places you in realistic, complex situations that require judgment and decision-making under pressure.

The beauty of SBT is that it contextualizes your traditional checkride tasks in missions that mimic the type of flying you will actually do.

This kind of operational environment also has another benefit: You’ll develop the habit of carefully and thoughtfully considering all aspects of the flight as it progresses.

SBT will also teach you to make and carry out realistic contingency plans to deal with unexpected events.

Handling Engine Failures in Multi-Engine Aircraft

Losing an engine in a multi-engine aircraft presents unique challenges. The FAA warns that mismanaging single-engine operations in light twins has led to many fatal accidents.

How do they happen? Here’s an example: If your critical engine fails during takeoff, you may be close to minimum control speed (Vmc). Any less speed or increase in angle of attack can result in an uncommanded yaw and roll toward the dead engine.

In contrast, an engine failure during cruise or approach is less risky since you typically have more altitude and airspeed to work with.

But even so, you should avoid go-arounds with only one working engine. In an engine failure, even though you lose 50% of available power, there’s an 80% loss of performance.

If you’re a multi-engine pilot, you should practice single-engine operations and emergency landings as much as you can.

The Role of Flight Simulators

Flight simulation is one of the most effective ways to practice engine-out procedures without real-world risks.

Modern training devices let you experience various emergencies in a controlled environment. You can practice dealing with an engine failure after takeoff or practice your reaction to a primary or multi-function flight display failure.

Even home flight simulators can reinforce emergency training by allowing you to practice deadstick landings, electrical failures, and other scenarios. With simulator software, you develop muscle memory and improve your ability to handle real emergencies.

Do you need an expensive simulator to get adequate training? No. Great instructors and great SBT programs equal excellent training in any aircraft or simulator.

Just remember that in emergency training, there are three keys to success:

- Plan for emergencies before takeoff. Always know your runway length, calculate accelerate/stop distances, and identify alternate landing sites in case of an engine failure.

- Review your plan before each flight. Just as professional pilots brief every takeoff and landing, you should mentally rehearse your emergency procedures before you fly.

- Practice regularly with an instructor. SBT with a qualified instructor is the best way to improve your emergency response skills.

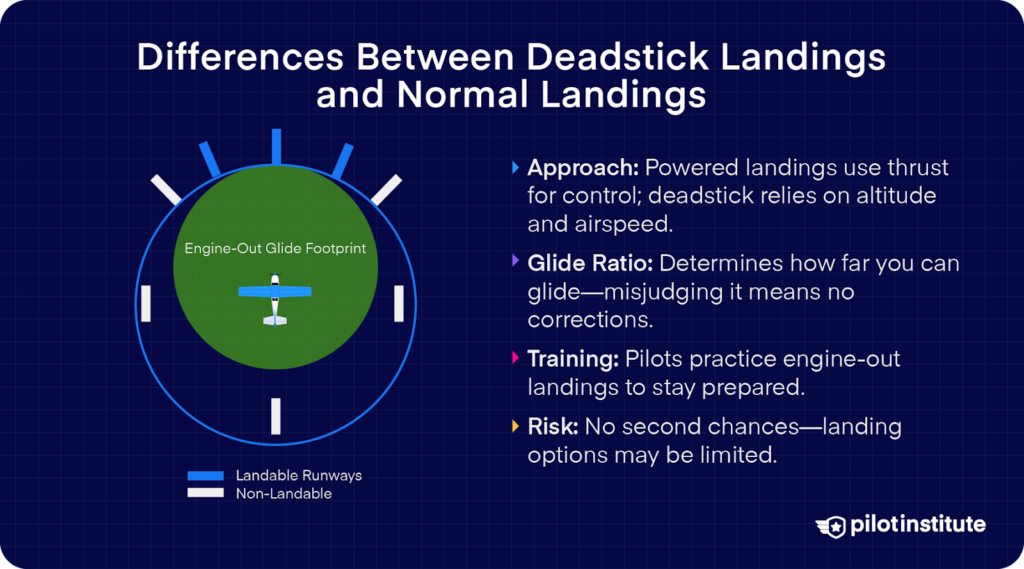

Differences Between Deadstick Landings and Normal Landings

How does a landing without engine power compare to a routine landing with full control?

They’re fundamentally different from normal landings. They involve precise energy management and quick decision-making.

Even though all aircraft can glide to some extent, deadstick landing presents unique challenges you should know how to handle.

Approach Control

One key difference is how you control your approach. In a powered landing, you can adjust thrust to fine-tune your descent angle. You have the tools to land precisely where you want. With just a few power adjustments, you can make last-minute corrections easily.

You don’t have that same flexibility in a deadstick landing. Once the engine quits, you’re relying entirely on altitude and airspeed to reach a suitable landing area.

How can you make sure the aircraft and everyone in it land in one piece? The moment you lose power, you must immediately establish the best glide speed to maximize distance.

There’s no second chance—every decision, from selecting a landing site to setting up the approach, must be made quickly and precisely.

Glide Ratio

Your aircraft’s glide ratio determines how far you can travel after an engine failure. For example, a Boeing 747-200 has a glide ratio of about 15:1. It can glide 150,000 feet (around 25 NM) from a cruising altitude of 10,000 feet.

The glide ratio isn’t a major concern in normal landings. You can always adjust power to compensate for altitude loss.

But in a deadstick landing, you must constantly manage your glide path to ensure you reach your target safely. If you misjudge the descent, you could come up short or overshoot the landing area with no way to correct it.

Pilot Training: Preparing for No-Power Landings

You train extensively for both powered and deadstick landings, but there’s a difference in focus. Normal landings involve learning approach techniques and power adjustments for various conditions.

With deadstick landings, you’ll need an added emphasis on situational awareness and energy management.

Private pilots practice simulated engine-out landings to build confidence, while glider pilots refine deadstick skills on every flight.

Commercial pilots train in simulators to handle complex scenarios, such as an engine failure at high altitude. These exercises ensure that when an actual emergency occurs, pilots remain calm and execute a controlled landing.

Risk Factors

Deadstick landings come with higher risks because success depends on variables beyond your control. The availability of suitable landing sites is a significant factor.

Landing on a smooth runway is ideal, but you might not have the same flexibility in an emergency. You could be forced to land in a field, on a road, or even on water.

Unlike a normal landing, where you can go around or make adjustments, a deadstick landing is final. Once you commit, you have to land.

But while normal landings are generally safer, you could still be at risk of an engine failure during critical phases if not managed properly. That’s why you are trained to always follow procedures.

Other Types of Landings

There are other types of landings to be aware of:

Emergency / Abnormal

- Forced (engine-out) landing.

- Precautionary landing.

- Partial-gear landing.

- No-flap / flapless landing.

- Off-airport landing.

- Contaminated-runway landing.

- Belly (gear-up) landing — touchdown with gear retracted.

- Bounced landing — hard rebound; risk of porpoising—execute a go-around if unstable.

Technique / Performance

- Short-field landing.

- Soft-field landing.

- Crosswind landing.

- Power-off 180 / accuracy landing.

- Downwind/tailwind landing.

Ops / Procedure

- Touch-and-go.

- Stop-and-go / full-stop.

- Circle-to-land (IFR).

- Autoland / CAT II–III.

Water Clarifier

- Water landing (seaplanes, normal).

- Ditching (emergency water landing in a non-seaplane).

Conclusion

Deadstick landings are a fundamental skill to learn in aviation safety. When you know what to do, you’ll be able to respond effectively to engine failures.

But the benefits go beyond just an emergency. You’ll also develop your skills in decision-making and aircraft control. Plus, you’ll know how to stick to FAA procedures.

There are plenty of resources out there that might just save your life, so equip yourself with knowledge and always fly safe.