-

Key Takeaways

-

How Non-Towered Airports Work

- Mastering CTAF Communication

- Understanding Traffic Patterns

-

Common Communication Mistakes

- Failing to Announce Positions and Intentions

- Using Improper Phraseology or the Wrong Frequency

- Overlooking Non-Radio-Equipped Aircraft

- Speaking Too Much or Too Little

- Failing to Update Intentions

- Interrupting or Overlapping Transmissions

-

Traffic Pattern Errors

- Misjudging Entry or Exit Points

- Flying Incorrect Altitudes or Patterns

- Cutting Into the Pattern

- Neglecting Other Traffic

-

Runway Selection and Incursions

- Determining the Active Runway

- How Runway Incursions Happen

- Avoiding Runway Incursions

-

Special Considerations: VFR, SVFR, and Departures

- Special VFR at Non-Towered Airports

- Safely Exiting the Pattern

- Transitioning to Controlled Airspace

-

Conclusion

Flying at non-towered airports can feel like stepping into a space where you’re both the pilot and air traffic controller.

Without the guidance of an ATC, it’s up to you and your fellow aviators to keep safe operations through proper communication and adherence to the standard procedures.

you’ll need to master the basics of situational awareness, traffic patterns, and CTAF communication can make non-towered operations not only manageable but smooth and predictable.

Let’s explore the common mistakes pilots make at these airports and how you can avoid them.

Key Takeaways

- Situational awareness and coordination help you safely navigate a non-towered airport.

- Communication and traffic pattern issues put everyone at risk, but they’re easily preventable.

- Runway incursions are caused by lapses in awareness and communication.

- Follow procedures when requesting an SVFR clearance or departing a non-towered airport.

How Non-Towered Airports Work

Flying at a non-towered airport takes some serious coordination and situational awareness. There’s no air traffic controller, unlike in towered airports. It’s just you and other pilots doing your own communications.

Does this sound intimidating? Well, you might be surprised that these airports run smoothly every day.

Mastering CTAF Communication

That’s because pilots follow a system to keep everyone on the same page–and it all starts with the Common Traffic Advisory Frequency (CTAF).

The CTAF is a radio frequency where pilots communicate with each other. It’s usually used in airports without an ATC.

Pilots coordinate their arrivals, departures, and ground movements in this frequency. It’s like an open radio station where every pilot announces and listens for updates about traffic in the area.

So, how do you use the CTAF?

You’ll need to properly transmit where you are and what you plan to do. At the same time, you also have to listen carefully to other pilots’ announcements.

The IPI format is a handy template for your transmissions. It’s the most efficient way to get information across as clearly as possible.

What does IPI stand for?

- Ident: Shorthand for identification, this is your callsign. In some cases, you’ll need to state your type of aircraft, current flight rules, and airport of origin.

- Position: Your position and altitude.

- Intention: What you plan to do or where you plan to fly.

Flying at a non-towered airport isn’t about doing everything on your own—it’s about working together with other pilots. Everyone shares the responsibility for keeping things safe and organized.

To operate safely, you need to scan for other aircraft visually and actively listen to the CTAF. You should also communicate clearly and follow established rules.

In short, follow the procedures and always use your eyes, ears, and mouth.

Understanding Traffic Patterns

The traffic pattern gives traffic structure and predictability at non-towered airports. This standard procedure spells out how you’ll approach, enter, and exit the airspace around the airport.

What are the parts of a traffic pattern? Its key elements include:

- Upwind leg: After takeoff, you fly straight out, climbing away from the runway.

- Crosswind leg: You turn 90 degrees to the upwind leg, flying perpendicular to the runway.

- Downwind leg: You fly parallel to the runway in the opposite direction of landing.

- Base leg: You turn at another right angle, heading toward the runway.

- Final approach: This is the straight path leading to your landing.

Common Communication Mistakes

We’ve established that good communication is the backbone of safe operations. Miscommunication creates chaos and confusion, which can lead to dangerous situations.

These mistakes are actually easier to make than you think, but they’re also easy to avoid.

So, what communication issues should you watch out for? Let’s dive in and discuss how you can avoid them.

Failing to Announce Positions and Intentions

One of the most frequent mistakes is neglecting to announce your status on the CTAF. Skipping a call when making a turn leaves others guessing. If other pilots don’t know where you are or what you’re planning, how can they adjust accordingly?

You should transmit every time you enter and exit the traffic pattern, make turns, and prepare to take off or land. Even if you think the airspace is empty, always assume that there’s someone who hasn’t called in yet.

Using Improper Phraseology or the Wrong Frequency

We practice using standard terms in aviation for a reason: to ensure communication is clear and consistent. Instead of saying something like, “I’m about to land on the runway,” you should say, “Springfield traffic, Cessna 1234, final runway 27, Springfield.”

Here’s another dangerous mistake: tuning in to the wrong frequency. If you’re on the wrong CTAF, no one will hear your calls, essentially leaving you invisible to other traffic. Always double-check the airport’s frequency before your flight.

Overlooking Non-Radio-Equipped Aircraft

Take note that not all aircraft in the pattern will be using the CTAF. Some older aircraft or ultralights might not have radios. Plus, even pilots with radios may not always monitor the frequency.

How do you handle this? By relying on your eyes as much as your ears.

Always keep a vigilant visual scan of the airspace. Look for aircraft entering the pattern without making radio calls. You might also spot them moving silently on the ground.

Once you spot them, try to identify any potential collision points, and take action to avoid them.

Do you remember the right-of-way rules? Under 14 CFR 91.113, you still follow “see and avoid” even if nobody is talking on the radio. Balloons sit at the top of the list, followed by gliders, then airships, and finally airplanes and rotorcraft. An aircraft towing or refueling another aircraft has priority over other engine-driven aircraft.

When you’re converging at the same altitude, you yield to the aircraft on your right. When you’re approaching head-on, both pilots should alter course to the right. And an aircraft on final or landing (and especially an aircraft in distress) has the right-of-way over other traffic in the area.

Speaking Too Much or Too Little

You might find yourself either rambling on the CTAF or keeping your calls too vague. Both extremes can be problematic.

Why is this? Long-winded transmissions clog the frequency, while overly brief or unclear ones leave others guessing your intentions.

Strike the balance of concise yet informative. The IPI format makes sure you don’t miss out on important details while still leaving time for other pilots to speak.

Failing to Update Intentions

Making an initial call is a good start, but it’s not enough if you don’t follow up on your next intentions.

For instance, if you announce entering downwind but fail to update on turning base, another pilot on the ground might think it’s safe to enter the runway. Keep everyone informed through each stage of the pattern.

Interrupting or Overlapping Transmissions

Are you quick to press the mic button? Jumping onto the frequency without listening first can lead to overlapping transmissions. Always pause and listen out to ensure the frequency is clear before speaking.

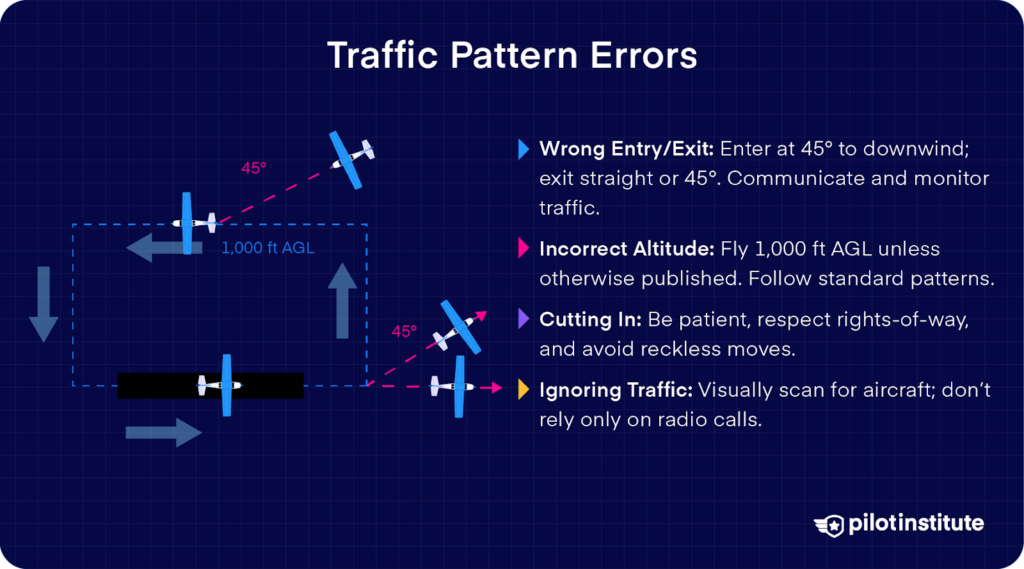

Traffic Pattern Errors

Aside from communication errors, you might also get in trouble for getting the procedures wrong, especially in the traffic pattern. Unfortunately, traffic pattern errors are common and can lead to conflicts or worse–accidents.

Now, let’s discuss the most common traffic pattern errors and how to avoid them.

Misjudging Entry or Exit Points

One of the most common mistakes is entering or exiting the traffic pattern incorrectly.

For instance, instead of entering at a 45-degree angle to the downwind leg, you might head straight to downwind without realizing it. Straight-in approaches or improper entry points often cause conflicts with other aircraft already in the pattern.

You should plan your approach to enter at the proper point and altitude. Pay close attention to the airport’s published traffic pattern in the Chart Supplement (formerly known as the Airport/Facility Directory or A/FD), since sectional charts do not display traffic pattern altitudes (TPAs).

Standard TPAs can often be derived using the airport elevation, but non-standard TPAs require verification in the Chart Supplement.

Actively monitor traffic by listening to radio communications, watching for aircraft visually, and using tools like TIS-B (Traffic Information Service – Broadcast), which is part of ADS-B In, if available.

At the same time, maintain situational awareness by understanding the pattern’s flow, anticipating where other aircraft might be, and adjusting your speed and position as needed.

Lastly, clearly communicate your intentions on the radio.

When exiting the pattern, continue straight out or turn 45 degrees to the pattern’s heading. Double-check that you’re clear of traffic and communicate before making additional maneuvers.

Flying Incorrect Altitudes or Patterns

Do you know the correct pattern altitude for your airport? Be careful not to get this wrong, or else you’ll disrupt the flow of traffic.

Pattern altitudes are typically 1,000 feet above ground level (AGL) for piston aircraft. Note that this depends on terrain, noise abatement areas, or specific airport requirements. Pattern altitude information is not shown on sectional charts but can be found in the Chart Supplement.

Flying non-standard patterns, like right traffic when the airport specifies left traffic, might also land you in trouble. Always follow the published pattern unless otherwise required, like when avoiding noise-sensitive areas or obstacles.

Cutting Into the Pattern

Patience is a virtue, but you might forget this in the heat of the moment.

Have you ever been tempted to race another pilot or cut ahead to save time? This often happens when you let impulsive or macho attitudes take over.

This mindset can lead to reckless decisions. While you may think you’re in full control, the truth is that pushing limits puts everyone in danger. You should respect other pilots and observe the rights-of-way rules.

Neglecting Other Traffic

How often do you focus only on your aircraft without paying attention to others? Getting tunnel vision can lead to dangerous situations, especially in a busy pattern. Not all pilots communicate their positions, so relying solely on CTAF calls isn’t enough.

Maintain a vigilant visual scan, looking for aircraft entering or already in the pattern. Check blind spots before turns, especially onto base or final, to avoid conflicts with unseen traffic.

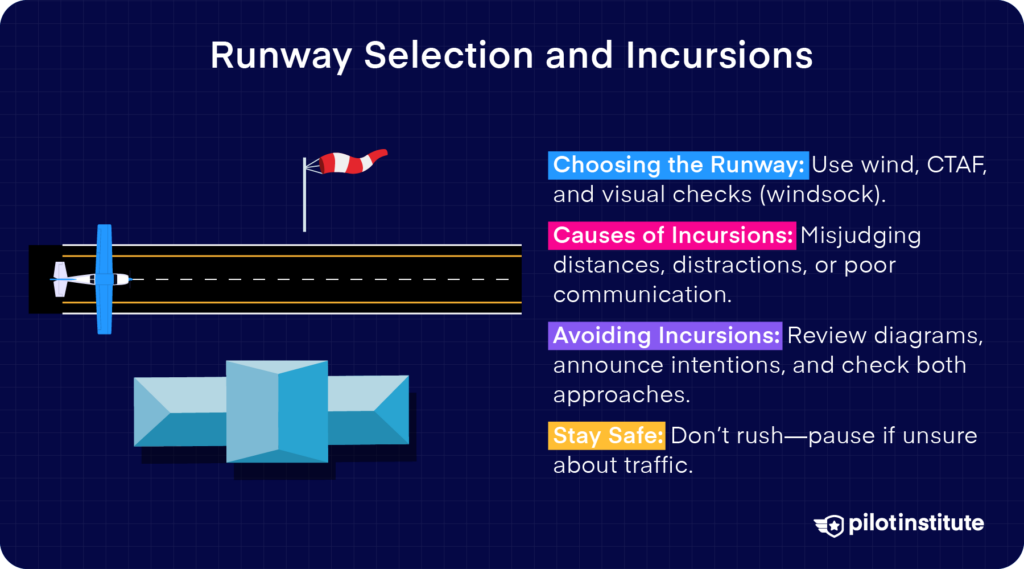

Runway Selection and Incursions

Another essential part of flying at a non-towered airport is choosing the correct runway. But without an ATC, this task is all up to you.

So, how can you make the best decisions?

Determining the Active Runway

Where is the active runway based? Wind direction.

Remember that aircraft perform best when flying into the wind because it reduces groundspeed, allowing for shorter takeoff and landing distances. Be sure to assess the conditions carefully.

Here’s a step-by-step checklist to find out which runway to use:

- Listen to CTAF traffic. Start by tuning in to the CTAF frequency. If other pilots are already using a particular runway, it’s usually best to follow their lead. This shouldn’t be the sole factor, though. You also have to–

- Determine the wind condition. Check the airport’s windsock or automated weather observation system (AWOS). A steady wind blowing from 210 degrees? Runway 21 is likely your best option.

- Consider obstacles or terrain. Some runways may have specific challenges for approach or departure that make them less ideal, even with favorable winds.

- Monitor sudden changes. Keep an eye out for shifting winds, which can make another runway more appropriate mid-flight.

Once you’ve determined the active runway, announce your intentions clearly on CTAF so others know your plan.

How Runway Incursions Happen

Sounds simple enough, right? Not so fast.

Even with a good system in place, complications can still occur. One of the worst possible consequences is a runway incursion. According to FAA Order 7050.1, a runway incursion is defined as “any occurrence at an aerodrome involving the incorrect presence of an aircraft, vehicle, or person on the protected area of a surface designated for the landing and takeoff of aircraft.”

Imagine rolling onto the runway while another aircraft is on short final. Incidents like this happen when pilots fail to announce their movements.

What other mistakes can lead to a runway incursion?

- Misjudging distances: You might assume you have enough time to cross a runway or take off before an approaching aircraft arrives.

- Losing situational awareness: Distractions in the cockpit or confusion about airport layout can lead to unintended incursions.

- Skipping communication: Failing to call out your position and intentions can leave others in the dark, increasing the risk of conflicts.

Avoiding Runway Incursions

You have to be vigilant and disciplined to avoid incursions. The good news is that there are many ways to stay safe.

Review the airport diagram before every taxi, even if the airport is familiar, and especially if it’s unfamiliar. Take note of the locations of runways, taxiways, and any hotspots where incursions are most likely to happen.

During your flight, always announce your intentions on CTAF. For example, you might say,

“Springfield traffic, Cessna 1234 back-taxiing Runway 15 for departure, Springfield traffic.”

When you’re about to cross or enter a runway, you should visually check both approaches, even if no one has announced their presence. And don’t rush into taking off or crossing if you’re unsure about other traffic. It’s better to wait a moment than put yourself and others at risk.

Special Considerations: VFR, SVFR, and Departures

Special VFR at Non-Towered Airports

Special VFR (SVFR) cannot be requested at non-towered airports because there’s no ATC to grant you the clearance. SVFR is only available in controlled airspace (Class B, C, D, or E surface areas) where ATC services are available.

You can contact Flight Service, but they cannot give you an SVFR clearance. Flight Service will contact the Air Traffic Control facility that oversees the airspace of your intended destination.

Safely Exiting the Pattern

So, you’ve done the procedures and are ready to exit the pattern. What do you do next?

Even if you’re departing from a non-towered airport, you should still plan ahead and coordinate before leaving. Here are the steps you should take:

- Announce your intentions. Call out your departure direction and runway on CTAF before starting your roll.

- Climb to pattern altitude. Maintain your position within the pattern until you reach pattern altitude before making turns.

- Depart efficiently. Exit the pattern in the direction you announced. If continuing straight out, climb to 500 feet above pattern altitude before turning on course to avoid conflict with inbound or crosswind traffic.

- Stay alert. Even if you’ve announced your intentions, don’t forget to scan and listen for other aircraft. You should adjust accordingly if there’s inbound traffic since they have the right-of-way.

Transitioning to Controlled Airspace

If your flight plan takes you into controlled airspace shortly after departure, follow these procedures:

- Plan your route. Determine the boundaries and altitudes of controlled airspace in advance. Use your sectional chart or GPS for a smooth transition.

- Monitor the appropriate frequency. Tune to the approach or center frequency as you exit the pattern and listen briefly before making your call.

- Contact ATC. Announce yourself clearly using the IPI format. For example:

“Approach, Cessna 1234, five miles west of Smithville, climbing through 3,500 feet, requesting flight following.” - Follow instructions. Acknowledge and comply with any squawk codes, headings, or altitude restrictions provided by ATC.

Note: While entering Class E airspace is common shortly after departure, ATC communication is not required for VFR flight in Class E. However, transitioning into Class B, C, or D airspace does require two-way communication and clearance.

Conclusion

Navigating at non-towered airports will require discipline, proper communication, and vigilance.

Perfecting your CTAF etiquette and avoiding common pitfalls like miscommunication or procedural errors helps you increase safety.

Flying at these airports is a collective effort based on mutual respect and clear communication.

Keep studying, and you’ll be well-equipped to handle the unique challenges of non-towered airport operations.