-

Key Takeaways

-

What Does Airworthiness Mean?

- The Two Conditions for Airworthiness

-

Regulatory Basis for Airworthiness

- Airworthiness Certificates

-

Pilot and Owner/Operator Responsibilities

- Pilot-in-Command (PIC) Responsibilities

- Owner/Operator Responsibilities

-

Required Aircraft Documentation (ARROW)

- Airworthiness Certificate (A)

- Registration Certificate (R)

- Airplane News Update

- Radio Station License (R)

- Operating Limitations (O)

- Weight and Balance Data (W)

-

Maintenance and Inspection Requirements

- Transponder, Altimeter, and Pitot-Static Inspections

- Emergency Locator Transmitter (ELT) Inspection

-

Airworthiness Directives (ADs)

- What Are ADs?

- Compliance With ADs

- Difference Between ADs and Service Bulletins

-

Inoperative Equipment and Minimum Equipment Lists (MEL)

- Minimum Equipment Lists (MELs)

- Procedures Without an MEL

-

Determining Airworthiness Before Flight

- Preflight Inspection

- Decision-Making

-

Consequences of Operating an Unairworthy Aircraft

- Safety Risks

- Legal Implications

- Impact on Insurance and Financial Liability

-

Conclusion

Airworthiness is one of those parts of pilot life we tend to take for granted. We check documents and sign off on inspections almost out of habit. Once we see the airworthiness certificate, we carry on with our preflight check without a second thought.

But for a good pilot, following the rules isn’t enough. They try to understand why we have these rules in the first place.

So together, let’s dig deeper into what “airworthy” really means, who’s responsible for keeping an aircraft that way, and how those requirements shape our decisions in the cockpit.

Key Takeaways

- An airworthy aircraft conforms to its type design and is in a condition for safe operation.

- The rules for airworthiness are written in Title 14 of the Code of Federal Regulations.

- Make sure your aircraft’s required inspections are up-to-date.

- Pilots are responsible for determining their aircraft’s airworthiness before flight.

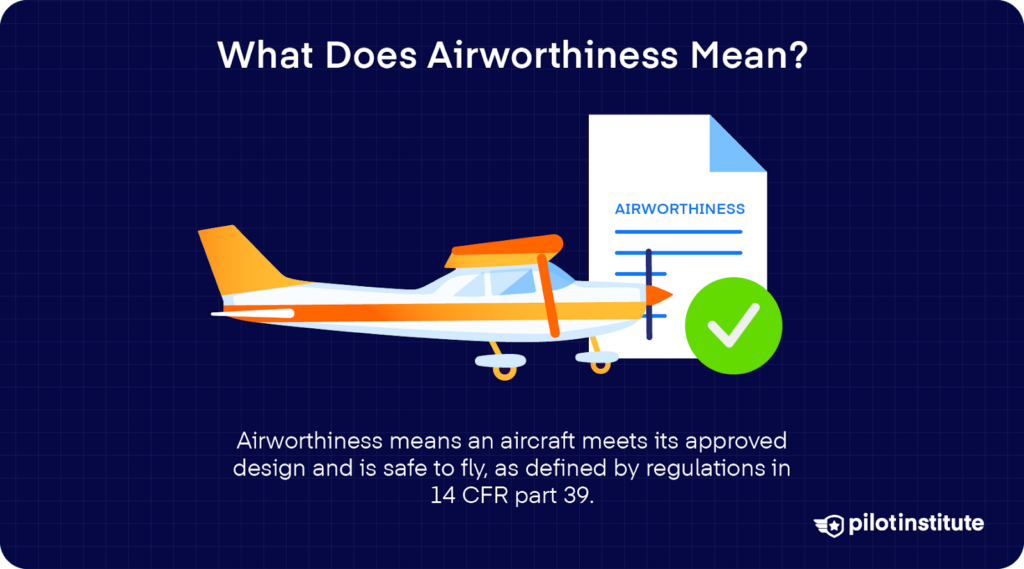

What Does Airworthiness Mean?

We pilots have our licenses and ratings to certify that we’re fit to fly. For aircraft, they have airworthiness. It’s the legal and practical standard that tells us an aircraft is truly approved for flight.

The United States federal government publishes a Code of Federal Regulations (CFR). This code describes 50 titles for areas subject to regulation.

Title 14 contains the rules covering aeronautics and space, which we call the Federal Aviation Regulations, or FARs. This is where we find the basis of airworthiness.

How does Title 14 define airworthiness? Under 14 CFR 3.5(a), an “airworthy” aircraft conforms to its type design and is in a condition for safe operation. You can find the details pertaining to airworthiness directives under 14 CFR part 39.

In other words, two key conditions must be met before an aircraft is considered airworthy. Let’s talk about them.

The Two Conditions for Airworthiness

Conformity to Type Design

While it seems obvious, your aircraft must first be what it is.

These specifications and more are all laid out in your aircraft’s Type Certificate Data Sheet (TCDS). Here, you’ll find the correct structure, systems, and safety equipment as approved for your specific aircraft.

So if you make any changes, they must be backed by FAA‑approved data. These could be from Supplemental Type Certificates (STCs) or FAA Field Approvals.

Condition for Safe Operation

But even if your aircraft fits perfectly in its design type, it can become unsafe if you don’t take care of it. Is your aircraft well-maintained? It needs to be free from damage, corrosion, or mechanical issues that could put safety at risk.

This means all components in your aircraft must function reliably. It must pass its scheduled inspections—annual, 100‑hour, or others—as required.

Regulatory Basis for Airworthiness

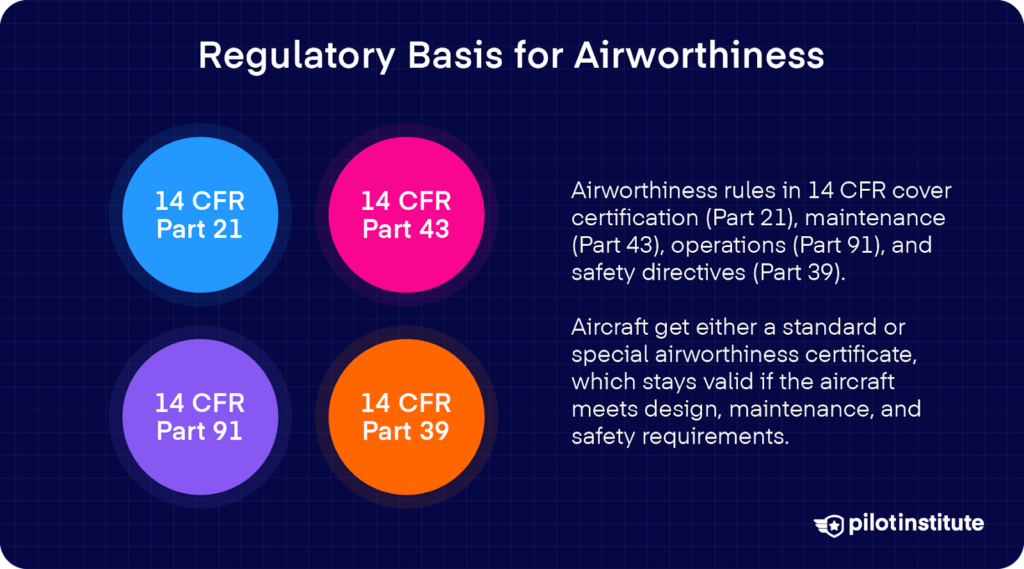

We’ve established that 14 CFR is our foundation of airworthiness. But where is this discussed, exactly?

In the U.S., airworthiness rules are spread across several parts of the code. Together, they make the foundation of how aircraft are certified, maintained, and operated.

To find how aircraft and parts earn their certification, read through Part 21. It sets procedures for type certificates, production certificates, and design approvals.

Are you looking for maintenance rules? Read through Part 43.

14 CFR Part 91 covers operational rules for flying certified aircraft. It talks about inspections like annual and 100‑hour checks.

The authority of the FAA to issue Airworthiness Directives (ADs) is written in Part 39. These directives are issued to fix known safety issues in aircraft or components.

Airworthiness Certificates

Because not all aircraft are made and used the same way, the FAA issues two types of airworthiness certificates: standard and special.

Which one does your aircraft need? Well, it’ll depend on its design and intended use. Let’s talk about it.

Standard Airworthiness Certificate

A standard airworthiness certificate applies to aircraft that hold type certification in the following categories:

- Normal

- Utility

- Acrobatic

- Commuter

- Transport

- Manned Free Balloons

- Special Classes of Aircraft

Special Airworthiness Certificate

The special airworthiness certificate covers aircraft that don’t meet requirements for standard certification. This includes categories such as:

- Primary

- Restricted

- Limited

- Light-Sport

- Provisional

- Experimental

- Special Flight Permits

For example, the experimental certificate covers aircraft used for things like research and development, showing compliance with regulations, crew training, exhibition, air racing, or market surveys.

On the other hand, a restricted certificate is given to aircraft used for specific jobs such as crop dusting, towing banners, or aerial surveying.

Validity

How long is the validity of an airworthiness certificate? While they have different uses, both standard and special certificates remain valid under the same conditions.

Your aircraft needs to:

- Conform to the approved design.

- Be in a safe operating condition.

- Have preventative maintenance and alterations be performed under 14 CFR parts 21, 43, and 91.

- Be registered in the United States.

As long as these requirements are met, the certificate stays active.

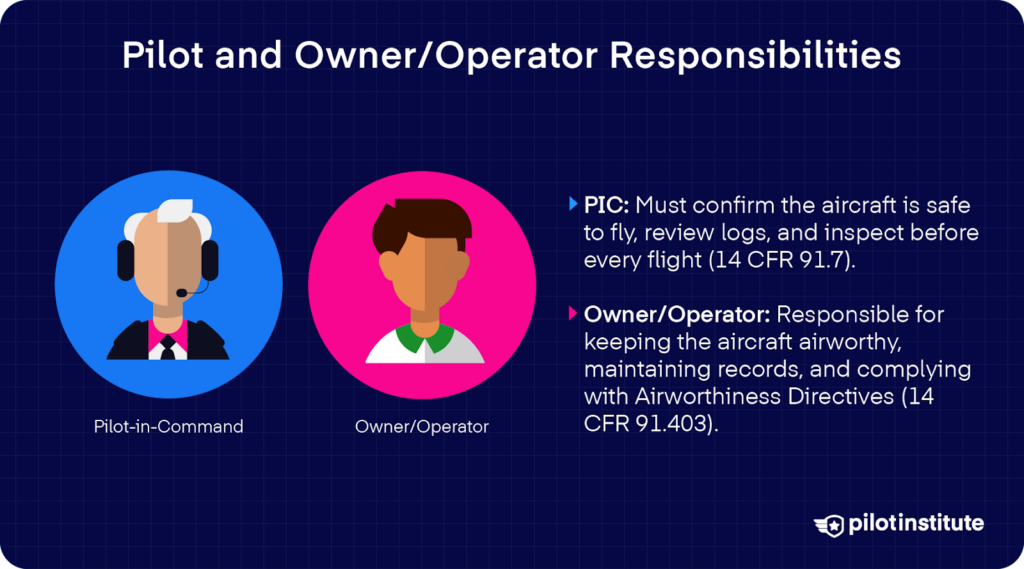

Pilot and Owner/Operator Responsibilities

Pilot-in-Command (PIC) Responsibilities

14 CFR 91.7(b) states that, “The pilot in command of a civil aircraft is responsible for determining whether that aircraft is in condition for safe flight”.

Notice how this doesn’t mention a mechanic or an operator. According to the law, this responsibility is all up to you.

So, how can you meet this duty? You need to carefully review maintenance logs, flight manuals, and required inspection records. Then, perform a thorough preflight inspection guided by the AFM/POH checklist.

Hopefully, you’ve been doing these thoroughly before every flight.

If any unairworthy mechanical, electrical, or structural condition occurs in the air, you are required by regulation to discontinue the flight. In such situations, wise decision-making and safety are your top priorities.

Owner/Operator Responsibilities

As outlined in 14 CFR 91.403(a): “The owner or operator of an aircraft is primarily responsible for maintaining that aircraft in an airworthy condition, including compliance with part 39.”

What does this mean? If you’re an owner or operator, the primary responsibility for keeping the aircraft airworthy falls on you.

In line with that, you should also keep clear records of any maintenance, repairs, or changes as required by 14 CFR 91.417. You should also follow all applicable Airworthiness Directives (ADs) within the deadlines.

Required Aircraft Documentation (ARROW)

You’re probably familiar with the acronym ARROW. This is a handy mnemonic for the documents that need to be onboard before every flight.

But why must we have these documents in the first place? And what does regulation say about these requirements? Let’s find out.

Airworthiness Certificate (A)

Remember that the airworthiness certificate proves that your aircraft meets design requirements. It also guarantees that the aircraft has been evaluated by authorities and considered safe for flight.

Your aircraft’s current airworthiness certificate must be on board and displayed at the cabin or cockpit entrance. It also needs to be legible to passengers or crew upon boarding.

Registration Certificate (R)

For U.S. aircraft, no one is allowed to operate a civil aircraft unless it carries proper proof of registration on board. This means your aircraft must have a valid U.S. registration certificate issued to the owner.

In any case, the key requirement is that your U.S.-registered aircraft must have valid U.S. registration documentation during flight.

It’s also important that your aircraft’s registration be current. The certificate used to expire every three years, though recent changes now extend it to seven years, so check your current renewal date carefully.

Radio Station License (R)

If you fly internationally or need to communicate with foreign stations, you must carry a current FCC-issued radio station license on board. Having one lets you operate your radio equipment abroad, and it’s valid for ten years. But if you’re only flying within the U.S., a radio station license is not required.

Operating Limitations (O)

Operating limitations are another mandatory document. They define the approved and safe operational boundaries of your aircraft.

Where can you find them? They’re usually in the POH/AFM, cockpit placards, and instrument markings. Your aircraft’s operating limitations are there as a reference for the certified safety margins of your aircraft.

Inspectors check for them routinely, and failing to have them onboard can lead to serious consequences. These limits must be current and accessible onboard; otherwise, your flight is not legally permitted.

Weight and Balance Data (W)

Since they’re established as operating limitations, current weight and balance documentation must also be on board your aircraft. This should include any recent changes made to affect weight and balance.

Remember the impact of weight and balance on your aircraft’s performance. 14 CFR 91.9 requires you to comply with the operating limitations specified in the approved Airplane Flight Manual/Pilot’s Operating Handbook.

These limits ensure that the airplane can operate properly without overloading any part of the structure. If specific loading patterns could affect safety, those should also be clearly defined.

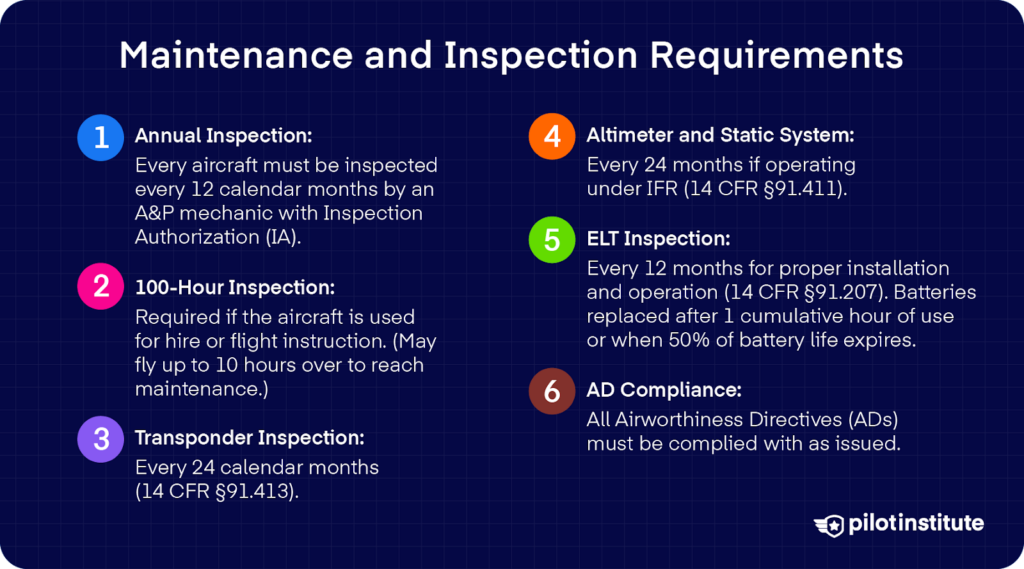

Maintenance and Inspection Requirements

To make sure every aircraft in the air is in shape to fly, they need to be regularly inspected and pass those inspections.

Every aircraft must undergo a full annual inspection no later than 12 calendar months after the last one.

Who should do this inspection? An A&P mechanic with Inspection Authorization (IA) must conduct this thorough check to legally return the aircraft to service.

If your aircraft is used for hire or flight instruction, it must get a 100-hour inspection every 100 flight hours. You’re allowed up to 10 extra hours to reach the inspection facility, but those hours count toward the next interval of the 100-hour inspection.

Transponder, Altimeter, and Pitot-Static Inspections

Under Instrument Flight Rules (IFR), you must have your altimeter, static system, and automatic altitude reporting system tested every 24 calendar months.

On top of that, your transponder needs to be inspected at the same 24‑month interval for any operation in controlled airspace requiring a transponder. This should be done by an authorized repair station.

Emergency Locator Transmitter (ELT) Inspection

Your Emergency Locator Transmitter (ELT) must also be inspected every 12 calendar months. The inspection includes checks for proper installation, corrosion, functional controls (including the crash sensor), and signal strength.

Your ELT has batteries that need to be replaced or recharged when 50% of their useful life is used, or after one hour of transmitter operation, whichever comes first.

Airworthiness Directives (ADs)

What Are ADs?

Sometimes, issues in aircraft, engines, propellers, or related equipment only show themselves after they’ve been rolled out to the market.

To address these problems, the FAA enforces Airworthiness Directives under Part 39. These directives take effect when the FAA finds a safety issue in a design that likely affects other similar aircraft.

Compliance With ADs

How can you stay updated? You can check FAA AD databases regularly, review notices from the manufacturer, and stay in close contact with your maintenance personnel.

You can even sign up for email delivery of new ADs and Special Airworthiness Information Bulletins (SAIBs), based on your aircraft type and make.

Once you comply with the directives in the AD, you’ll have to log it in your maintenance record. That entry should include:

- The AD number and revision date.

- The method you used to comply.

- The date and total aircraft time at completion.

- The signature with the certificate number of the person who performed the work.

Difference Between ADs and Service Bulletins

Manufacturers sometimes issue Service Bulletins (SBs) to inform operators about potential issues, upgrades, or safety-related concerns.

But how are they different from ADs? Service bulletins are manufacturers’ recommendations. They are not legally binding unless they are:

- Incorporated into an Airworthiness Directive (AD).

- Are part of the FAA-approved Airworthiness Limitations section of a maintenance manual.

- Are part of an FAA-approved inspection program.

But even though they’re technically not mandatory, it’s good practice to treat an SB the same way you would an AD.

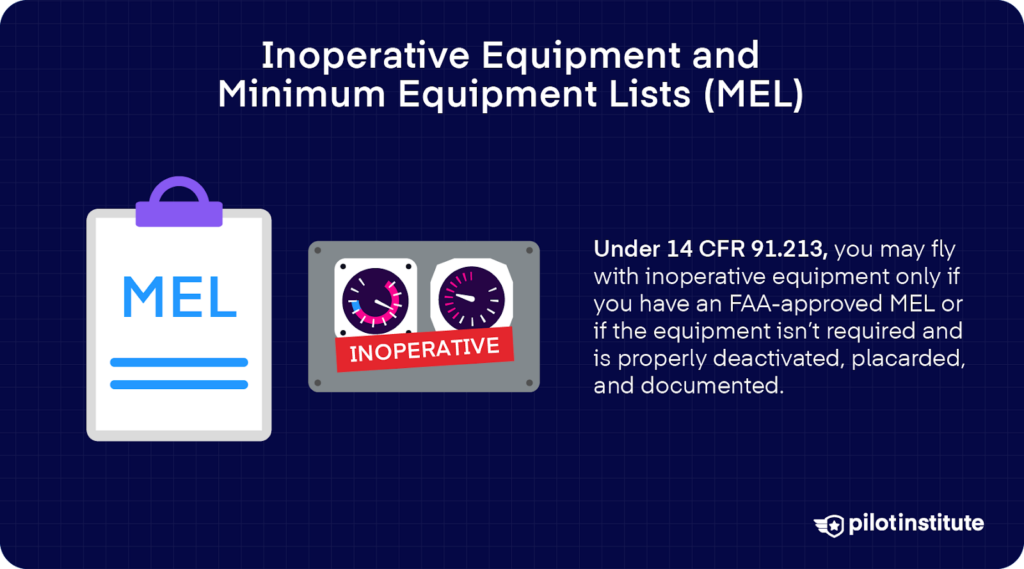

Inoperative Equipment and Minimum Equipment Lists (MEL)

14 CFR 91.213 was written so that even though different aircraft have different equipment, they at least have all of the essentials to operate safely.

You may operate an aircraft with missing or inoperative equipment, but only under two conditions:

First, you can use a FAA‑approved Minimum Equipment List (MEL) specific to that aircraft.

And second, if you don’t have an MEL, you must follow the provisions under 14 CFR 91.213(d). The inoperative or missing equipment must not be required by the type certificate, the aircraft’s equipment list, or any applicable performance equipment list.

It also must not be required by 14 CFR 91.205 or an Airworthiness Directive.

There might also be additional equipment needed depending on your type of flight. So make sure that any inoperative equipment also comply with the Kinds of Operation Equipment List (KOEL), if your aircraft has one.

The KOEL indicates the specific equipment you’ll need for different types of operation, such as Day‑VFR, Night‑VFR, IFR, or flight into known icing. You’ll typically find this in your aircraft’s POH or AFM.

But if your aircraft doesn’t have a formal KOEL, then only the operating limitations in the POH apply.

Minimum Equipment Lists (MELs)

What’s an MEL? It is a document tailored to a specific aircraft listing which items can be inoperative while still being able to fly legally.

It is built from the Master Minimum Equipment List (MMEL) provided by the FAA and developed together with the manufacturer. The MEL needs to get FAA approval and a Letter of Authorization (LOA). Without the approved MEL and LOA, you must comply with 91.213(d) instead.

Once approved, the MEL functions like a Supplemental Type Certificate.

When using the MEL, you’ll need to follow the procedures strictly. Make sure the components your aircraft does have are all in good working condition before taking off.

Procedures Without an MEL

Now, if your aircraft doesn’t have an MEL, you’ll need to follow the guidelines written in 14 CFR 91.213(d). So, how can you be sure you’re flying legally?

According to the rule, the malfunction must be removed or deactivated. It must also be clearly marked with an “Inoperative” placard.

If the removal or deactivation of the equipment constitutes maintenance, an entry describing the work performed must be made in the maintenance records in accordance with 14 CFR 43.9.

And finally, a pilot who is certificated and appropriately rated for the aircraft, or a person who is certificated and appropriately rated to perform maintenance on the aircraft, must determine that the inoperative item does not present a hazard to the flight’s safety.

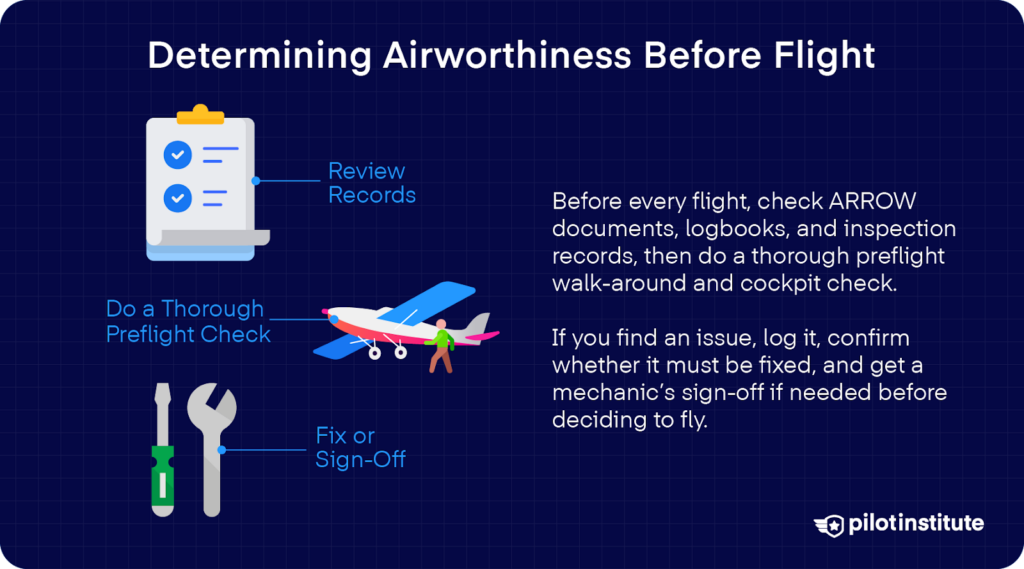

Determining Airworthiness Before Flight

You’re just as responsible for your aircraft’s condition—and that starts before every flight. Begin with the ARROW documents, then review the logbooks for the airframe, engine, propeller, and appliances.

Check if all inspections (annual, 100-hour, ADs, and maintenance) are current. Look at the date, total time, and type of the last inspection, including any service bulletins.

Make sure the entry is signed with the mechanic’s name, certificate number, and type. Finally, confirm there are no missing signatures and that deferred items are properly documented.

Preflight Inspection

Once that’s done, it’s time for your walk-around. Each pilot has their own system depending on their style. But to keep things organized, you can divide this into two parts.

After you head to your aircraft, while you’re still outside, begin with an external check. You should walk around the aircraft and inspect structural areas. Can you spot any damage, corrosion, or wear?

Check the tires, brakes, and landing gear for condition. And as you confirm the fuel and oil levels, check for any leaks and properly secure the caps.

Once you get inside the cockpit, test that all instruments, avionics, switches, and controls are functioning correctly. Make sure that the circuit breakers are all in.

Decision-Making

Based on what you’ve gathered so far, you’re now equipped to make an informed decision about your aircraft’s airworthiness. Remember that this includes whether the aircraft conforms to its type design.

So, what if you spot an issue? Stop and assess the situation immediately. Log the discrepancy clearly in the maintenance or discrepancy log so it’s officially documented.

If the component in question is required by regulations (like for type certification, equipment lists, ADs, or MEL), then it needs to be fixed before you fly.

On the other hand, if it’s non-essential for that flight, you should follow the steps we discussed under 14 CFR 91.213(d).

After repairs or deactivation are completed, it should get a sign-off from an authorized mechanic. Only then is it safe and legal to proceed.

But with that said, airworthiness is just one factor in making a sound go/no-go decision. You should also consider the weather, your proficiency, and aircraft performance limitations.

Consequences of Operating an Unairworthy Aircraft

Whether they were aware of it or not, some pilots have flown unairworthy aircraft in the past. And oftentimes, their choice to proceed has led to some serious consequences.

Safety Risks

The main purpose of certifying airworthiness is to ensure all aircraft in the air are in good and safe operating conditions. Flying without it automatically means that you’re putting your safety at risk.

Your chances of running into mechanical failure, loss of control, or any other catastrophic accident increase significantly. Any issues that would’ve been caught during an inspection go unchecked, and that makes it much more likely for something to go wrong in flight.

If this happens at the worst possible time, you’ll have little to no margin to recover. This doesn’t just endanger you and your passengers; it also puts people on the ground at risk.

Legal Implications

But even if you manage to land safely, you’re not off the hook just yet. Legally speaking, flying an unairworthy aircraft is a violation of FAA regulations.

When you get caught—which you most likely would—the FAA has a wide range of enforcement tools it can use.

This can include civil penalties (fines), or the suspension or revocation of your pilot certificate. In severe situations, law enforcement and criminal charges are a real possibility.

Impact on Insurance and Financial Liability

Flying an unairworthy aircraft is dangerous and illegal. But on top of these, it is also expensive.

Insurance policies often include strict clauses that require compliance with airworthiness standards. If you’ve flown an unairworthy aircraft, insurance companies may refuse to honor claims.

Think of the costs you’ll have to shoulder out of pocket. You’ll need to pay for repairs, liabilities from passenger or third-party injuries, and legal defense expenses.

Conclusion

The aviation industry wouldn’t be as safe as it is now without airworthiness. It guarantees that every aircraft in the sky—from a tiny Cessna to an enormous Boeing—meets the highest standards of safety.

While it may seem overwhelming, the FAA has defined airworthiness for us as clearly as possible. After reading through the rules, one thing becomes evident: Airworthiness is a team effort.

The FAA, mechanics, operators, and pilots alike are responsible for creating a safe and productive airspace.