-

Key Takeaways

-

Why Friction Matters Long After Touchdown

- Lubrication vs. Hydroplaning

-

The Physics of Hydroplaning

- Building the Water Wedge

- Dynamic Lift vs. Tire Pressure

-

Three Modes Pilots Must Recognize

- Dynamic Hydroplaning

- Viscous Hydroplaning

- Reverted-Rubber Hydroplaning

-

Factors That Tip the Scales

- Aircraft & Tire Variables

- Runway & Weather Variables

- Operational Variables

-

Calculating and Predicting Hydroplaning Speed

- Horne/NASA Formula Walk-Through

- Quick-Reference Table

-

Consequences: What Happens When Contact Is Lost

- Loss of Directional Control

- Braking Effectiveness Drop

-

Detecting Hydroplaning in Real Time

- Cockpit Cues

- External Cues

-

Mitigation Starts Before Takeoff Roll

- Pre-Flight & Dispatch Actions

- Tire Maintenance & Inflation

-

Techniques During Approach, Touchdown, and Rollout

- Approach Setup

- Touchdown Tactics

- Braking Strategy

-

Regulatory & Training Guidance

- FAA / EASA Documents Pilots Must Know

-

Common Misconceptions Debunked

- “Grooved runways eliminate hydroplaning.”

- “Heavier airplanes hydroplane less.”

- “Hydroplaning only matters above 100 knots.”

-

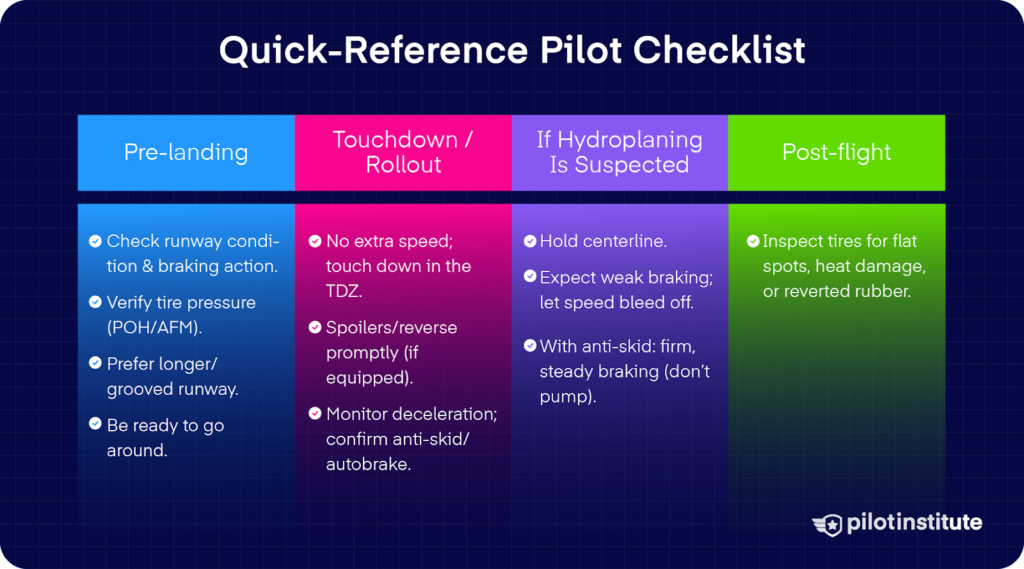

Quick-Reference Pilot Checklist

- Pre-landing

- On Touchdown

- If Hydroplaning Is Suspected

- Post-flight

-

Conclusion

In 1999, a Qantas 747 overran the runway in Bangkok during heavy rain. The aircraft touched down fast, met standing water, and lost braking effectiveness.

But hydroplaning doesn’t care if you fly a widebody or a trainer. Hydroplaning can affect anything with tires, from trainers to transport jets. Smaller aircraft aren’t immune, because lower tire pressures mean hydroplaning can begin at surprisingly low speeds.

Let’s break hydroplaning down step by step. You’ll see the physics, the modes, the speeds, the risk factors, and what you can do to stay ahead of it.

Key Takeaways

- Hydroplaning happens when water lifts the tire off the runway, reducing braking and steering friction.

- It occurs as dynamic, viscous, or reverted rubber hydroplaning.

- Hydroplaning depends on tire pressure, water depth, and speed.

- You can prevent it with proper tire inflation, speed control, firm touchdown, and effective braking technique.

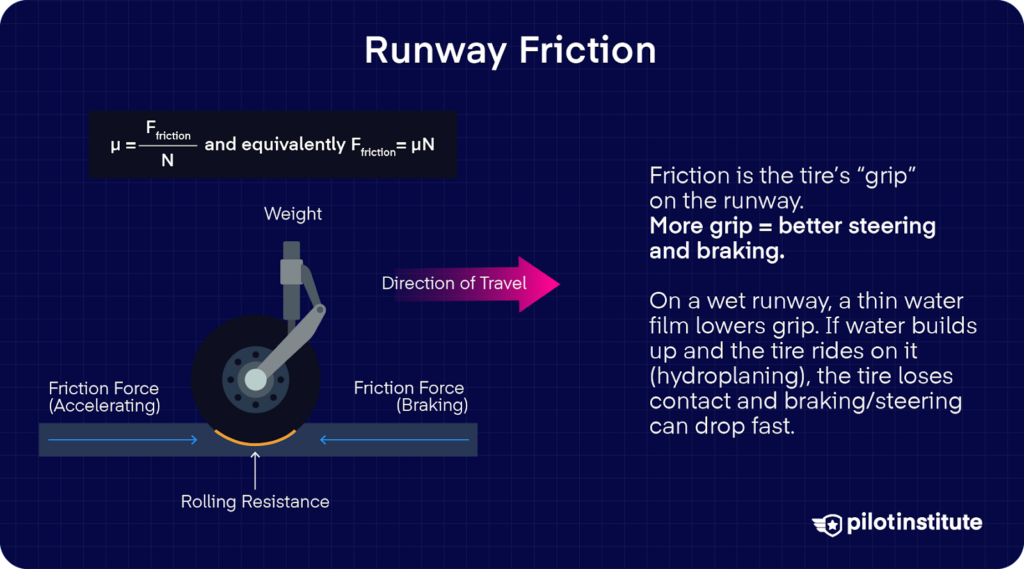

Why Friction Matters Long After Touchdown

It all starts with friction, which you can think of as how “sticky” the tires are to the runway, especially right after you touch down.

In physics, we can describe friction with a simple formula: μ = F/N.

Here, μ represents how much friction is available. F is the braking or sideways force from the tires, and N is how hard the wheels are pressed into the runway.

So what does that actually mean for you? Less friction means less aircraft braking coefficient and less aircraft braking response.

Lubrication vs. Hydroplaning

Water complicates all of this. You already know that a wet runway feels slicker. A thin film of water lowers friction but still allows some grip.

What happens when it gets worse? Hydroplaning is the tipping point where grip nearly disappears.

Water builds up under the tire and lifts it off the pavement. Braking can fade fast, and pilots often report a sudden loss of deceleration and control.

The Physics of Hydroplaning

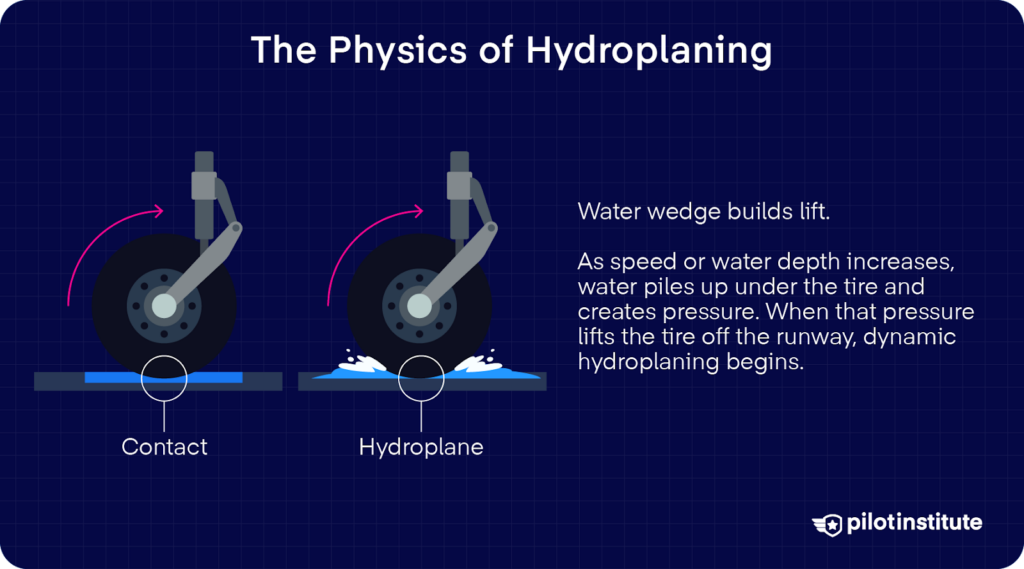

Building the Water Wedge

Before hydroplaning begins, water has to get pushed out of the way. But as your aircraft rolls faster, or as the water gets deeper, that water doesn’t go away as easily.

The water starts to pile up in front of the tire and forms what pilots call a water wedge. That wedge can create pressure in front of the tire that resists being pushed aside.

Eventually, that pressure gets so strong that it lifts the tire up off the surface.

Dynamic Lift vs. Tire Pressure

When does dynamic hydroplaning begin? When that upward water pressure equals the downward force from the tire pushing into the pavement. At the instant they match, the tire lifts, and hydroplaning takes over.

It is this hydrodynamic pressure that lifts the tire.

Three Modes Pilots Must Recognize

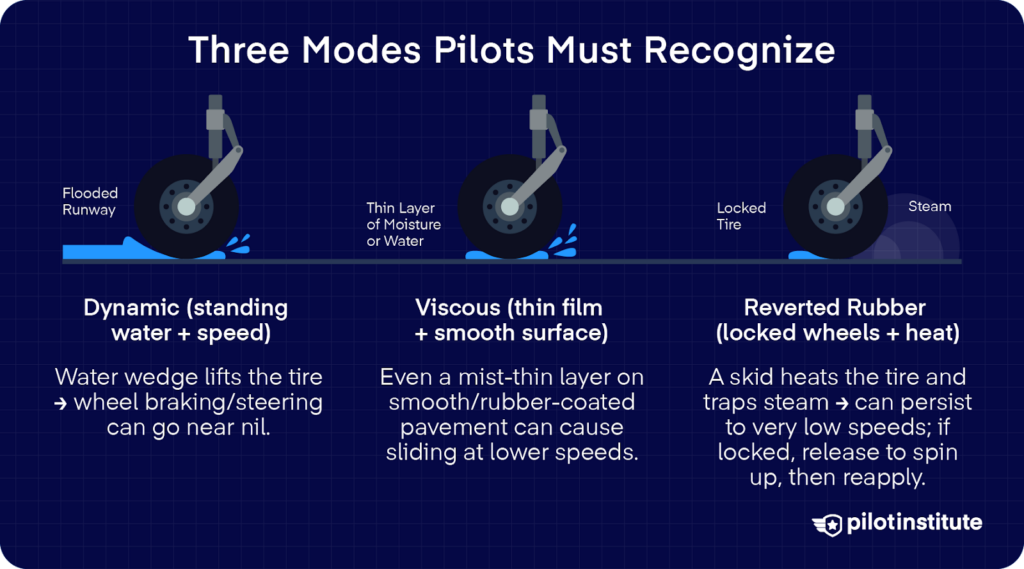

Dynamic Hydroplaning

Dynamic hydroplaning is a high-speed problem. You need a thin but considerable layer, about one-tenth of an inch, spread across the runway.

As your airplane rolls faster and the water gets deeper, the water resists being pushed aside. Then, it builds pressure in front of the tire and forms a wedge of water underneath it.

What happens when that pressure keeps rising? At a certain speed, called the hydroplaning speed, the water pressure matches the load the tire normally carries. The tire lifts off the runway.

Once that happens, the rubber is no longer touching pavement. Wheel braking and steering effectiveness can drop to near zero while the tires ride on a water wedge

But keep in mind that that speed only marks the start of hydroplaning. The condition can continue even as you slow down.

Viscous Hydroplaning

Viscous hydroplaning is a quieter, sneakier problem, and it doesn’t need much water at all. You’re dealing with the thickness of a mist, about one-thousandth of an inch.

But even at that thickness, the water’s viscosity is enough to keep the tire from cutting through to the pavement.

What actually happens under the tire? The tire rides on top of the fluid instead of pushing it aside.

The rubber never really reaches the runway surface, even though the water layer is extremely thin. Because of that, viscous hydroplaning can happen at much lower speeds than dynamic hydroplaning.

Surface texture has a lot to do with viscous hydroplaning. Smooth or rubber-contaminated touchdown zones can behave like polished pavement when wet.

So does a touchdown zone coated with rubber from countless previous landings. Rubber fills in the runway’s tiny grooves and pores, which makes the surface behave like polished pavement when it gets wet.

Reverted-Rubber Hydroplaning

Reverted rubber, sometimes called steam hydroplaning, can start with just a thin film of water on the runway.

Heavy braking locks the wheels, and the tires stop rolling and begin to skid. That skid creates intense heat right at the contact point.

What does that heat do? It changes the rubber itself. The rubber touching the runway softens and reverts toward its uncured state. That softened rubber forms a tight seal against the surface.

Water can no longer escape from beneath the tire. Trapped water heats up, turns into steam, and that steam lifts the tire off the runway.

This type often shows up after dynamic hydroplaning. You touch down fast, hydroplane, and instinctively hold the brakes to slow the airplane.

But as speed drops, the tires finally touch the runway again. They stay locked. Heat builds, and reverted rubber hydroplaning takes over.

Why is this one so dangerous? You may not realize it has started. The airplane keeps sliding, and braking still feels ineffective.

Worse, this condition can persist to very low groundspeeds, sometimes 20 knots or less. You might expect traction to return by then, but it does not.

Luckily, the remedy is simple. Release the brakes and let the wheels spin back up. Then, reapply moderate braking.

That break in braking allows water and steam to escape and lets the tires regain contact with the runway.

Factors That Tip the Scales

Aircraft & Tire Variables

Dynamic hydroplaning is closely tied to tire inflation pressure. How so? Tire pressure sets how hard it is for water to lift the tire.

According to the formula by Walter Horne, the hydroplaning speed, vP, equals 9 times the square root of the tire pressure in PSI, p.

But not all types of tires behave the same. Newer bias-ply designs, type-H tires, and radial-belted tires can hydroplane at speeds lower than what Horne’s equation predicts.

So when does Horne’s formula actually apply? It applies to smooth or closed-pattern tread tires. Those treads do not give water many escape paths. It also applies to rib-tread tires when the runway is covered by enough water to flood the grooves completely.

Why does this still matter if the formula is imperfect? Horne’s equation gives you a conservative estimate of hydroplaning speed.

While not entirely precise, it pushes you to think in terms of risk. Use it to stay well clear of the point where water can start lifting the tire.

Runway & Weather Variables

Runway slope affects your chances of hydroplaning because water can pool on flatter surfaces. That’ll give more depth for water to interfere with contact.

Pavement texture makes a difference, too. Grooved surfaces and porous friction courses are designed to let water drain quickly from the footprint of the tire.

Smooth or worn surfaces trap water and increase that risk. Intense rainfall can replenish water faster than it drains. Cool pavement temperatures slow evaporation, leaving water on the surface longer.

Operational Variables

Your touchdown speed relative to your reference landing speed (vREF) matters a great deal. If you carry extra speed into the flare and don’t get onto the runway soon, you spend more time at higher groundspeed before the weight is fully on the wheels.

That means your tires are still rolling up to speed over standing water in the tread. They spend longer in a speed range where hydroplaning forces are strongest.

A deep layer of water in the touchdown zone should immediately get your attention. Why that area? That is where you need tire grip the most, right at the moment you touch down.

If conditions suggest aquaplaning is likely and you notice this before landing, the safest move is to fly the go-around.

Thrust reversers, spoilers, and autobrake don’t stop hydroplaning by themselves. They do influence how quickly you get out of the high-speed band.

Just be mindful not to exceed normal EPR levels when you deploy reverse thrust. Otherwise, you put yourself at risk of rudder blanking, which complicates directional control, especially when you’re dealing with a crosswind.

Finally, a controlled and smooth but firm touchdown puts the aircraft’s weight onto the wheels as close to the touchdown zone and as soon as possible.

Private Pilot

Study Sheet

Grab a printable PDF that highlights must-know PPL topics for the written test and checkride.

- Airspace at-a-glance.

- Key regs & V-speeds.

- Weather quick cues.

- Pattern and radio calls.

Calculating and Predicting Hydroplaning Speed

Horne/NASA Formula Walk-Through

Now, let’s go back to Horne’s formula for calculating the minimum hydroplaning speed. Let’s look at two examples, one for a Cessna 172 and one for a Boeing 737.

If a small aircraft like a Cessna 172 has tires inflated to about 29 psi, take the square root of 29 as roughly 5.4. Multiply that by 9, and you get about 48.47 knots vp.

If a larger transport like a Boeing 737 has main tire pressures near 200 psi, the square root of 200 is about 14.1. Multiply by 9, and the hydroplaning speed comes out to about 127.27 knots vp.

Quick-Reference Table

| Tire Pressure (psi) | Vp (kt) | Typical Aircraft |

| 29 | 48 | Cessna 172 |

| 87 | 84 | King Air 350 |

| 200 | 127 | Boeing 737 NG |

| 241 | 140 | Airbus 350 main |

Remember that landing at higher than recommended touchdown speeds will expose you to a greater potential for hydroplaning. And once hydroplaning starts, it can continue well below the minimum, initial hydroplaning speed.

Consequences: What Happens When Contact Is Lost

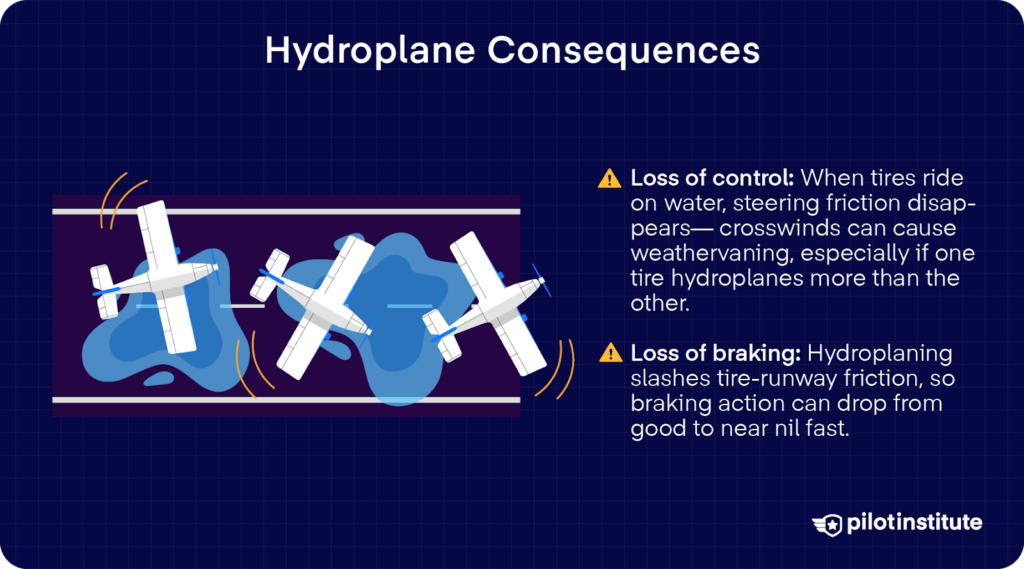

Loss of Directional Control

When your aircraft wheels are floating on a sheet of water instead of gripping pavement, they can’t provide the static friction you need to steer.

This becomes especially obvious in a crosswind. And if one tire hydroplanes more than the other, the aircraft can start to weathervane into the wind. The wind pushes the tail around toward the upwind side while the forward motion carries you downwind.

Braking Effectiveness Drop

The classic way pilots describe this with numbers is by referring to braking action reports. Pilots use terms like good, medium, poor, and nil to describe how much deceleration they actually get when braking on a given surface condition.

These terms correlate with friction coefficients. Good indicates a relatively higher braking coefficient and nil means negligible braking.

When hydroplaning happens, the friction coefficient between the tires and the runway drops dramatically. Hydroplaning can reduce braking action to nil because the tires are no longer pressing on the surface where brakes can work effectively.

Detecting Hydroplaning in Real Time

Cockpit Cues

You feel physical feedback when hydroplaning starts. If you don’t feel the usual resistance when you apply the brakes even though your speed is still high, that’s a strong clue.

Rudder or nosewheel steering inputs do not produce the expected response. You try to correct the direction, but the aircraft seems slow to respond or continues sliding without turning as you’d expect.

Groundspeed doesn’t bleed off the way it should. Based on runway length and expected performance, you should be slowing by now. Instead, deceleration feels weak. In some cases, it can even feel like you’re picking up speed.

External Cues

Outside the cockpit, you can see brake skid marks. If you apply brakes and the main gear tires leave no regular rubber skid marks on a wet runway, it may indicate the wheels are not gripping the surface because they are hydroplaning.

Also, water spray behavior is telling. If you see a continuous “rooster tail” rising and trailing behind the main gear even as you slow down, that can indicate the tires are “plowing” water.

Mitigation Starts Before Takeoff Roll

Pre-Flight & Dispatch Actions

FAA guidance and some operating rules use an added 15% margin for wet/slippery runways in planning/TOA assessments, but the FAA cautions that this still may not reflect real-world wet stopping performance.

But what if you don’t have wet or contaminated runway landing data to work with? Take the dry, factored landing distance from your preflight planning, calculated under the applicable operating rule.

Then, you apply the factors from the table below.

| Runway Condition | Reported Braking Action | Factor to Apply to (Factored) Dry Runway Landing Distance* |

| Wet runway, dry snow | Good | 0.9 |

| Packed snow, compacted snow | Fair / Medium | 1.2 |

| Wet snow, slush, standing water, ice | Poor | 1.6 |

| Wet ice | Nil | Landing is prohibited |

That step only applies when no specific wet or contaminated data exist. Note also that these factors already account for the additional 15 percent margin.

Tire Maintenance & Inflation

An underinflated tire changes shape as soon as it touches the runway. The contact patch gets wider and flatter.

What does that do? The flattened shape blocks the tread grooves, and water has nowhere to escape. As water piles up under the tire, pressure builds.

That pressure pushes upward against the airplane’s weight. The large, flat contact patch actually makes this easier.

The weight is spread over a larger area, which means less pressure pushing down through the water. Less downward pressure makes it easier for the tire to lift off the surface.

So is it better to just overinflate your tires? Absolutely not. Too much air makes the center of the tire bulge outward, and the contact patch shrinks.

With less rubber touching the runway, there is less tread available to move water out of the way. The tire also becomes stiff. It cannot flex and conform to small runway irregularities, which further reduces grip on a wet surface.

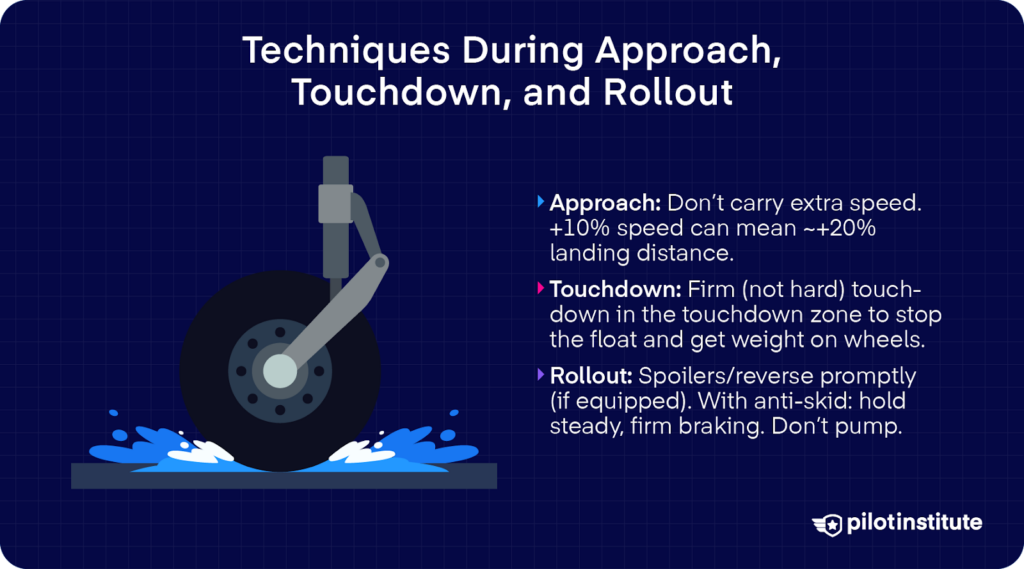

Techniques During Approach, Touchdown, and Rollout

Approach Setup

Extra speed has consequences. Even a slight excess over vREF turns into extra energy crossing the threshold. That energy pushes the touchdown point farther down the runway.

And on a wet surface, that means less runway remaining for braking and a higher risk of hydroplaning.

Touchdown Tactics

A firm, positive landing beats a greaser every time, especially on a wet surface.

How do you do that? You accept a higher touchdown sink rate and a slightly steeper approach. A firm, positive landing on a wet surface makes sure the wheels make solid contact.

This is more important than a soft touchdown, since it helps break through the water layer and puts weight on the wheels for effective braking.

That shortens the distance spent flying while the runway slides by underneath you.

Once the wheels are down, transition quickly to stopping. Maximum manual braking, applied as soon as conditions allow, minimizes the braking distance.

Extra knots mean extra energy, and extra energy demands more runway. That extra distance can quietly set you up for an overrun.

On both dry and wet runways, a 10 percent increase in final approach speed leads to about a 20 percent increase in landing distance.

Braking Strategy

You need to move quickly once the main gear touches down. Full lift spoiler deployment should happen right away.

Start de-rotation and deploy thrust reversers. They put weight on the wheels, which allows the brakes to work effectively.

Spoilers and speed brakes are especially important. They dump the lift and transfer the airplane’s weight onto the landing gear. That weight is what gives braking bite.

Manual spoiler deployment, though, comes with a hidden cost. At about 118 knots, the airplane is covering roughly 200 feet every second. A two-second delay adds almost 400 feet to the stopping distance.

And if your aircraft has autobrakes, it also has anti-skid. The proper braking technique with anti-skid is firm pressure. Hold it, increase it if needed, but do not pump the brakes.

What happens if the wheels start to lock? The anti-skid system should step in.

It releases brake pressure for a moment and reapplies it as soon as the tire regains grip. The system reacts far faster than any human can.

Regulatory & Training Guidance

FAA / EASA Documents Pilots Must Know

- AC 91-79B talks about landing on wet and contaminated runways. It explains landing risks, braking action reports, RCAM use, and landing performance planning. It also guides SOPs and training to reduce runway excursions.

- AC 25-31 explains how takeoff performance data must account for wet and contaminated runways.

- AC 150/5320-12C focuses on runway design and maintenance. It was made to help airport operators reduce hydroplaning risk and keep tires in contact with the surface during wet operations.

- SAFO 19001 helps pilots and operators apply consistent surface condition codes in landing performance planning.

- EASA certification specifications, such as CS 25.1591, detail how contaminated runways affect large aircraft performance. These standards are in line with ICAO and FAA practices.

Common Misconceptions Debunked

“Grooved runways eliminate hydroplaning.”

Grooved runways are great, but they don’t eliminate hydroplaning. Grooves increase drainage and let water escape from under the tires more quickly, which reduces the buildup of a water wedge that can lift the tire.

But grooves cannot remove all the water instantly. They can’t guarantee zero hydroplaning risk, especially in very heavy rain or standing water conditions.

“Heavier airplanes hydroplane less.”

You may have heard pilots say that heavier weight helps prevent hydroplaning because it supposedly presses the tire harder into the runway. That is a myth.

Hydroplaning is governed primarily by tire inflation pressure and speed, not by the aircraft’s weight on the wheels.

When hydroplaning begins, it’s because the water pressure under the tire equals the pressure the tire is exerting on the surface from its inflation and load.

The water lifts the tire off the surface and removes contact, no matter how heavy the aircraft is.

“Hydroplaning only matters above 100 knots.”

That idea comes from confusing dynamic hydroplaning with the other types of hydroplaning.

Dynamic hydroplaning typically happens at higher speeds when a substantial water layer builds under the tire, but there’s also viscous hydroplaning.

Viscous hydroplaning can occur at low taxi and rollout speeds when a very thin film of water exists on a smooth or rubber-coated runway surface.

Even a tiny layer of water, especially over micro-smooth areas or rubber buildup, can prevent the tread from making solid contact and allow sliding with much lower speeds.

Quick-Reference Pilot Checklist

Pre-landing

- Verify tire pressure against the POH/AFM, so you know your estimated hydroplaning speed (vp) from tire psi and runway condition.

- Compute or review the hydroplaning estimate based on tire inflation.

- Check RCAM and braking action reports in NOTAMs or ATIS.

- If available, plan to use a grooved and/or longer runway.

- Be ready for a go-around or missed approach if you are still airborne, and the hydroplaning risk or runway overrun risk looks high.

On Touchdown

- Deploy spoilers/speed brakes right after the wheels touch.

- Engage reverse thrust promptly as configured aircraft systems allow to supplement wheel braking, especially where wet runway performance data counts reverse thrust in stopping distance.

- Confirm autobrake engagement if your aircraft has it.

- Monitor deceleration cues versus expected performance. If braking feels weak or deceleration is much lower than expected, stay alert for hydroplaning.

If Hydroplaning Is Suspected

- Maintain heading and track centerline with rudder.

- Keep touchdown speed as slow as possible.

- Once the nose-wheel is lowered to the runway, apply moderate braking.

- Raise the nose and use aerodynamic drag to decelerate to a point where the brakes become effective.

- Apply brakes firmly until reaching a point just short of a skid. At the first sign of a skid, release brake pressure and allow the wheels to spin up.

- Hold brake pressure with anti-skid logic where available.

- Continue to use reverse thrust within limits to decelerate while the brakes lack grip. Follow AFM/QRH reverse-thrust limits and directional-control procedures.

Post-flight

- Inspect tires for flat spots or heat damage caused by skidding or prolonged sliding on water.

- Look for signs of reverted rubber, which happens when locked wheels get hot and trap water under the tire.

- Check the fuse plug thermal relief on wheels that may have overheated during a high-energy rejected take-off or hard braking.

Conclusion

Hydroplaning is not a rare edge case. It is a predictable result of physics. It is also something you can manage.

You do that by respecting your aircraft’s limits and staying in control before and after touchdown. You also do it by using every tool and data available.

The encouraging part is this: the science is well-understood, and the techniques are trainable.

Review your procedures. Practice them in the simulator. Brief them before every wet runway operation.