-

Key Takeaways

-

Who This Guide Helps

-

Regulatory Basics Made Simple

- Timeline of Changes

-

Defining the Airplanes

- Complex Aircraft: Old School Complexity

- Technically Advanced Aircraft: Glass Rules

- Quick-Reference Comparison

-

Meeting the 10-Hour Requirement

- Three Acceptable Paths

- Logging It Correctly

-

Frequently Asked Questions

-

Skills & Checkride Implications

- What the DPE Will Expect If You Flew a TAA

- If You Train Only in a Complex

- Bridging the Gap

-

Choosing the Right Aircraft Strategy

- Cost & Availability Analysis

- Risk Management & Insurance

-

Training Tips for Success

- Scenario-Based Avionics Practice

- Avoiding Typical Errors

-

Beyond the Checkride

- Staying Current in Both Worlds

- Monitoring Evolving FAA Definitions

-

Conclusion

The Arrow is down for maintenance again, but the G1000-equipped Cessna 172 is wide open. Will those hours still move you closer to the ride?

Since 2018, the FAA’s rule change has started to include the capability of advanced avionics. And yet, many applicants and even instructors are still unsure how that affects their commercial pathway.

Are you one of these pilots? Let’s break it all down. We’ll define each aircraft type and show you how to plan wisely.

Key Takeaways

- Complex aircraft have retractable gear, flaps, and a controllable-pitch prop

- TAA aircraft have a glass cockpit, GPS, and a two-axis autopilot

- Complex time builds mechanical and systems skills, but costs more to train and maintain

- TAA time boosts automation and situational awareness but reduces hands-on mechanical practice

Who This Guide Helps

You’re likely a private pilot trying to juggle a full-time job and a tight budget. There’s that looming goal of hitting 250 hours required for the commercial certificate. You may find yourself asking, “Do I hustle into complex aircraft time now or later?” You need guidance that respects your time, your wallet, and your goals.

You could also be a CFI hunting for talking points you can use during student consults or stage checks.

When students ask if they must fly retractables or whether logbook entries will stand up to a Designated Pilot Examiner’s (DPE) scrutiny, you’ll need clear and reliable answers.

On a larger scale, school owners or FBO operators might be trying to decide whether to refurbish an existing Arrow or upgrade the fleet with G1000-equipped Cessna 172s.

Which choice gives you the most flexibility, return on investment, and student appeal?

You don’t have to guess your way through these issues. We’ll give you the clarity you need.

Regulatory Basics Made Simple

Let’s dissect the regulations and see what rules really affect your decision. We’ll look at each part to understand how they all fit together.

14 CFR 61.129(a)(3)(ii): The “Special Aircraft” (10-Hour) Bucket

When you apply for a commercial certificate, 14 CFR 61.129(a)(3)(ii) says you need 10 hours of training in any combination of these aircraft:

- A complex airplane.

- A turbine-powered airplane.

- A Technically Advanced Airplane (TAA).

Essentially, whichever aircraft you fly and for how many hours each is up to you.

This rule gives you flexibility and freedom. You can use one or all of them for the 10 hours, as long as whatever you use meets the qualifications.

14 CFR 61.1: What “Complex” Means

What makes a complex airplane? 14 CFR 61.1 defines it as an airplane that has all three of these features:

- Retractable landing gear.

- Flaps.

- Controllable-pitch propeller.

This includes airplanes with a digital engine and propeller control system, like a Full Authority Digital Engine Control (FADEC).

14 CFR 61.31(e): Your Complex Endorsement

Thinking of flying a complex airplane? To act as pilot in command (PIC), 14 CFR 61.31(e) requires both ground and flight training in a complex airplane, or in a simulator or training device that accurately represents one.

Your instructor must also find you proficient in operating its systems, and they need to give you a one-time logbook endorsement.

There are, however, a couple of exceptions. You don’t need this training or endorsement if you logged pilot-in-command time in a complex airplane or an equivalent simulator before August 4, 1997.

You’re also exempt if you completed approved ground and flight training under a Part 135 program. You must pass a Part 135 competency check in a complex airplane or equivalent simulator. Just make sure it’s documented correctly in your logbook.

Timeline of Changes

While it’s great to have flexibility now, it wasn’t always this way. Earlier Practical Test Standards (PTS) once required the initial commercial pilot checkride to be done in a complex airplane. So, how did we get here?

In 2016, the FAA issued a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) to change commercial training rules to allow TAA in place of (or alongside) complex or turbine aircraft.

They also issued Notice N 8900.463 on April 2018. It directed Designated Pilot Examiners (DPEs) and training providers to follow the new policy even before the ACS revisions.

The FAA published the Final Rule that adopted those changes on June 27, 2018, and the ACS (Airman Certification Standards) was revised to reflect the new policy.

So, why this shift? One of the main reasons is that glass cockpit/advanced avionics skills are now far more relevant for pilots heading into Part 121 or Part 135 operations.

Many commercial operations rely on sophisticated avionics and navigation systems. This is the FAA’s way of evolving the training pipeline with the real world.

At the same time, it eased the burden of finding or maintaining complex aircraft for every student.

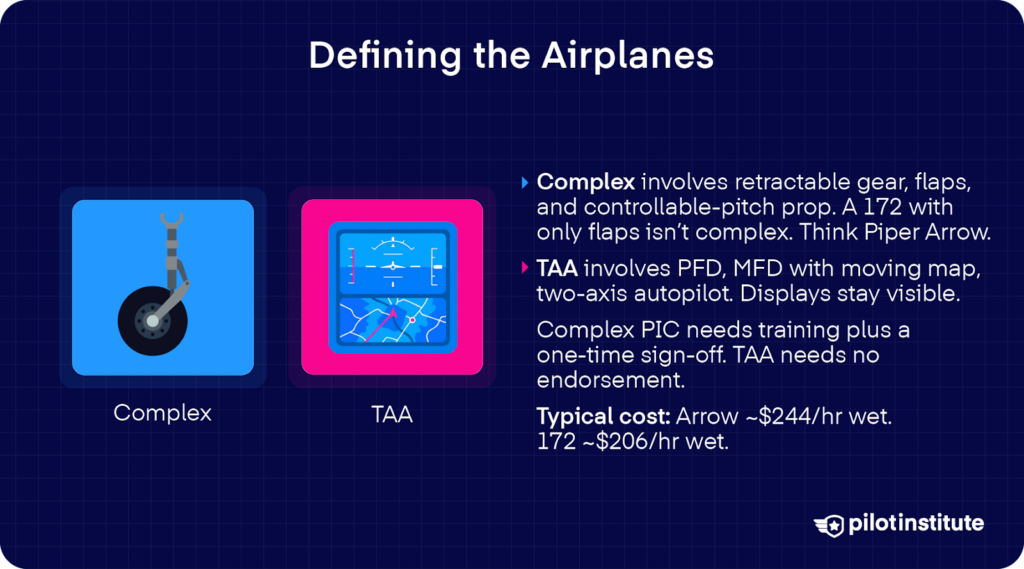

Defining the Airplanes

We’ve seen what the regulations say, but what are these airplanes you might fly? Let’s put faces and gear on the rules so you can ask better questions when deciding.

Complex Aircraft: Old School Complexity

Remember that a complex airplane has all three: retractable landing gears, flaps, and a controllable-pitch propeller. So, if your Cessna 172 has flaps, does that make it a complex airplane? Not unless it also has the other two requirements.

Complex airplanes are like mechanical systems calling for your attention. You’ll deal with retractable gear driven by electric motors or hydraulic actuators.

Then there’s the controllable-pitch propeller, which lets you change blade angle to get the best efficiency in cruise or climb.

Ever seen a Piper PA-28R Arrow? That’s a complex airplane. Other examples are the Cessna 172RG and the Beechcraft Sierra.

Technically Advanced Aircraft: Glass Rules

If a complex airplane feels vintage, a technically advanced airplane is all about avionics and automation. So, what makes a TAA? Under 14 CFR 61.129(j), it should have:

- An electronic Primary Flight Display (PFD) showing, at minimum, the standard flight instruments (airspeed, attitude, heading, altimeter, vertical speed, turn coordinator)

- An electronic Multifunction Display (MFD) with at least a moving-map GPS navigation that continuously shows the airplane’s position

- A two-axis autopilot, integrated with the navigation/heading system

Also, the display elements from the PFD and MFD must be continuously visible. Pretty self-explanatory, it should not be hidden behind menus or toggled screens.

How does an aircraft become a TAA? Just as an example, many older airframes upgrade their panels by adding a Garmin G3X display plus a GFC 500 autopilot.

Quick-Reference Comparison

| Feature | Complex | TAA | Both Possible? |

| Retractable gear | Yes | Not required | Yes (e.g., C182RG with G1000) |

| Two-axis autopilot | Optional | Required | Yes |

| Endorsement needed | Yes (14 CFR §61.31(e)) | No | If both: still need Complex |

| Typical rental rate | ~$244/hr wet | ~$206/hr wet | Varies by aircraft/avionics |

Seeing as you can fly either a TAA or a complex airplane, the choice of where you’ll log your hours is entirely up to you. Let’s look at them side-by-side to make a better comparison.

FAA Requirements

When it comes to FAA requirements, a complex airplane must have retractable landing gear, flaps, and a controllable-pitch propeller.

TAA, on the other hand, is not required to have retractable gear or a controllable-pitch prop. But what it does require is a two-axis autopilot, which is not mandatory for most complex aircraft.

Endorsement

Flying complex aircraft as PIC requires specific ground and flight training plus a logbook endorsement, whereas flying a TAA does not.

The Cost

In terms of rental and operating costs, complex aircraft tend to carry a premium. Rental rates vary significantly based on location and operator, but a Piper Arrow is often more expensive per hour than a Cessna 172.

For example, renting a Piper Arrow could set you back by US$244 per hour wet. Non-complex 172s often rent for around US$206 per hour wet.

Meeting the 10-Hour Requirement

Three Acceptable Paths

You’ve read the regulations, and now it’s time to make a game plan. How will you meet that 10-hour special aircraft requirement? You’ve got plenty of options, let’s talk about them.

All Complex

You could choose to fly all 10 hours in a complex airplane. It’s easy to see the benefits. First, you become deeply familiar with the systems early, so you won’t have to switch later in a time crunch.

If your checkride or job path will require complex operations, this gives you more confidence.

The downsides are cost and availability. Complex aircraft are often in high demand, with higher rental and maintenance rates.

That can make scheduling harder, not to mention heavier on your wallet.

All TAA

A second option is to fly all 10 hours in a TAA (non-complex) aircraft. In this case, you rely purely on your advanced avionics without dealing with retractable gear or prop systems.

Another big advantage is that many TAA aircraft are more available. They tend to be less expensive and easier to maintain.

However, you’ll be missing out on hands-on experience with mechanical complexity. Also, you’ll still need to upgrade your training later to cover gear/prop systems if you want experience in a complex aircraft.

Hybrid Path

Why not fly both? You split your 10 hours between TAA and complex airplanes (or even turbines). Maybe 6 hours in a fixed-gear TAA, then 4 hours in a complex.

Splitting your time helps you manage costs while still getting exposure to different systems. Scheduling will be more flexible, and you’ll be less at risk of being locked out if a complex is unavailable.

That said, though, you’ll have to switch between aircraft types and juggle learning two aircraft types at the same time for only a short while. You could end up not mastering one type to the depth you’d like.

Turbine-Powered Airplane

Finally, there’s the turbine-powered airplane route, also allowed under 14 CFR 61.129.

If you can access a turbine aircraft (or turbine complex), that time counts. Turbine time often brings credibility and strengthens your experience in jet aircraft.

If you have access to a turbine aircraft (such as a turboprop) and suitable instructor support, you could log all or part of the 10 hours there.

Turbine time might count for other job pipelines. But while it’s seen as high value, the price tag for your training will be considerably higher.

If complex airplanes are hard to come by, turbine-powered ones are even harder. Training in these aircraft is less practical for many students unless your school or club already has them in its fleet.

Logging It Correctly

The DPE will take a look at your logbook before your checkride. You want to make sure they’ll clearly see that you’ve met the requirements, so how can you log your hours properly?

Let’s say you flew a technically advanced Cessna 172S equipped with a Garmin G1000. The flight time was 01+12, and this was made in compliance with the 10-hour requirement. Your entry could look something like:

Aircraft type: C172S

Dual received: 1.20

Remarks: TAA (C172S G1000) per 14 CFR 61.129(a)(3)(ii), Maneuvers: chandelles, eights-on-pylons

That entry does several things. It states the amount of dual instruction and identifies the aircraft and avionics. It cites the regulatory basis and mentions which maneuvers were performed.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Is a G5 plus iPad a TAA?

Simply having a Garmin G5 paired with an iPad does not satisfy the FAA’s definition of a technically advanced airplane. Remember, a true TAA has all the required components installed, and all with continuous visibility.

The G5 is a versatile instrument display, and the iPad is supplemental. But they’re not part of the certified avionics needed to qualify as TAA.

- Can simulators or flight training devices substitute for the 10-hour complex/TAA/turbine requirement?

The 10 hours of “special aircraft” training under 14 CFR 61.129 must be in an actual airplane (whether complex, TAA, or turbine). Simulator or flight training device time cannot count toward that requirement.

But that’s not to say that simulators don’t have a place in your training. Up to 50 hours of training in an approved full flight simulator or flight training device representative of the airplane class can be credited toward the overall aeronautical experience.

Skills & Checkride Implications

Even though you’re no longer required to fly a complex aircraft during your commercial checkride, your DPE may still grill you on special-aircraft systems during the oral. And if you’re applying for a multi-engine or type rating, this is almost certainly guaranteed.

What the DPE Will Expect If You Flew a TAA

What if most or all of your training has been in a TAA? The DPE will likely expect you to demonstrate mastery of automation and fallback procedures.

You should be able to fly a coupled climb. You could first be tasked to engage the autopilot with navigation guidance, then hand-fly raw data when the autopilot is disconnected. Your biggest challenge here is to climb without losing situational awareness.

Be ready to diagnose a failure of the AHRS (Attitude/Heading Reference System) and transition to “reversionary mode.” This is where the system consolidates or shifts displays to a single functioning screen to preserve flight data.

If You Train Only in a Complex

If you focused on classic retractable-gear aircraft, expect questions about mechanical systems and failure modes.

The oral exam might dive into emergency gear extension procedures and what happens if a prop governor fails.

Before the flight, be ready to show the manual gear extension procedures. That could be how you’d hand-crank or use mechanical backup to extend the landing gear.

Bridging the Gap

If you want to be ready for anything the examiner throws at you, try splitting your training between TAA and complex aircraft.

You’ll get the best of both worlds. This strategy gives you hands-on experience with automation and solid skills in mechanical systems. It also shows the examiner that you’re adaptable and well-rounded.

Choosing the Right Aircraft Strategy

Cost & Availability Analysis

So, TAA or complex? One of the things it’ll come down to is the cost. We’ve talked about how complex rental rates tend to be higher than those of TAAs, but there’s more to costs than that.

Dispatch reliability is another factor you need to think about. Which one will help you save time?

Complex aircraft have more systems that can fail. They’ve got landing gear motors, actuators, and prop governors. If the gear system fails, the aircraft may be grounded for days or weeks for maintenance.

Risk Management & Insurance

Then, there’s the insurance requirement. Many flight schools and rental operators enforce these rules because their insurance policies demand it.

For instance, you could be required 25 hours of complex time and a 2-hour dual checkout for a retractable 172RG. And for a glass-panel 172S G1000, the same policy allows solo only after 5 hours in G1000 plus a 1-hour dual checkout.

So, why the big difference? One word: risk. Retractable-gear aircraft have more complex mechanical systems, which means more chances for things to go wrong. Insurers and operators know this, so they take a more conservative approach when it comes to solo privileges.

Training Tips for Success

Let’s talk about practical drills and habits you can build so your time in TAA or complex doesn’t feel like trial by fire. You want to keep your workload manageable.

Scenario-Based Avionics Practice

One powerful drill you can run is to program the missed approach while hand-flying in turbulence.

Can you also practice at home? By all means! You can use a G1000 desktop simulator or virtual cockpit trainer.

Avoiding Typical Errors

Many pilots forget small things that can cause big trouble.

One common mistake is leaving the CDI source on GPS instead of switching to the localizer during an ILS or LOC approach. What happens next? The navigation needle drifts, and final guidance becomes confusing, right when precision matters most.

Touch-and-goes in retractable-gear aircraft bring another classic error: forgetting to lower the gear. Calling out “gear down, three green” could just save you from a belly landing.

And don’t forget flap limits. Deploying flaps too early, before you’re under VFE, can do more harm than good.

Beyond the Checkride

Your checkride is just the beginning. To maximize value from both complex and TAA flying, here’s how to keep building on your progress.

Staying Current in Both Worlds

Consider alternating your aircraft usage to keep both retractable-gear and TAA skills fresh. Just to give you an idea, you can fly a steam-gauge or classic retractable every third flight to keep your instincts sharp.

Low-cost simulators and desktop trainers go a long way. Devices like the Redbird TD (trainer device) or home cockpit setups help you practice buttonology without the expensive rental fees.

Try to do approach programming, autopilot mode changes, and logic drills at home or in a sim. You’ll build confidence so that your skills come naturally during a real flight.

Monitoring Evolving FAA Definitions

The regulatory landscape is not static, and you’ve got good reason to keep your eyes peeled. Because technology evolves fast, there’s always the potential for refinements to what “electronic advanced avionics” means.

Stay alert for future NPRMs and FAA policy changes. What counts as a “technically advanced airplane” today might expand tomorrow. If the definition shifts again, you’ll be ready to adapt your training.

Conclusion

You’ve now got a clear idea of how “complex” and “TAA” compare. How will you meet the 10-hour requirement? Pick the strategy that fits your budget and goals.

However you map out your logbook, every hour is a chance to sharpen your judgment and gain valuable experience. Go schedule that training and log that endorsement. Keep both your mechanical instincts and automation instincts alive.

You’ve got the roadmap, and now it’s time to fly your own path and build a skillset to be proud of.