-

Key Takeaways

-

What Is a Power-on Stall?

-

Recognizing the Signs of a Power-on Stall

- Reduced Airspeed

- High Pitch Attitude

- Stall Warning Horn

- Buffeting

- Poor Control Feel

-

Steps to Recover From a Power-on Stall

- 1. Lower the Nose (Pitch)

- 2. To the Firewall (Power)

- 3. Clean Up

- 4. Climb Out

-

Differences Between Power-on and Power-off Stalls

- Power Setting

- Configuration

- Recovery

-

How to Practice Power-on Stall Recovery Safely

- Altitude

- Traffic

- Coordination

-

Conclusion

Power-off stalls can be anxiety-inducing for student pilots when they first experience them. They might feel scary at first, especially on your stomach. But mastering recovery techniques is a skill that helps keep you safe in the sky.

A power-on stall occurs when the airplane’s nose rises too high, and the angle of attack becomes too steep, disrupting the airflow over the wings.

A sudden drop can feel alarming. But knowing what to do next is life-saving. It can mean the difference between a safe flight and a dangerous one.

This guide will show you how to spot a power-on stall. We’ll then walk you through the recovery process. This will help you handle it like a pro if it ever happens.

In aviation, the sooner you react, the better. It means everything.

Key Takeaways

- Power-on stalls mimic a stall during the flight’s takeoff, departure, and go-around phases.

- Ability to readily identify the signs of an impending stall, including the buffet and stall warning horn.

- The angle of attack must be reduced to recover from a power-on stall.

- Ensure the aircraft is coordinated during the entire maneuver to prevent a spin.

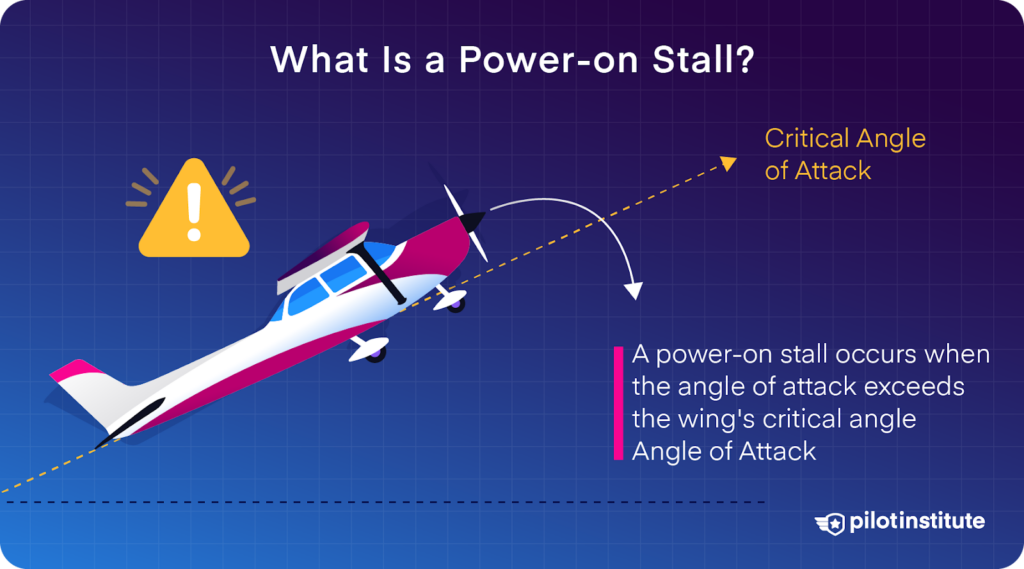

What Is a Power-on Stall?

Like any stall, a power-on stall occurs when the angle of attack exceeds the wing’s critical angle. This creates boundary layer separation, resulting in a loss of lift. Remember that a wing can stall at any altitude and airspeed as long as the critical AOA is exceeded.

According to the Airmen Certification Standards (ACS), a power-on stall occurs when an aircraft pitches up at a high angle of attack with at least 65% engine power. This maneuver is important and must be performed during your check ride.

It simulates a stall during the takeoff or departure phase when the aircraft has a high power setting and pitch attitude. So, it is usually performed with only takeoff flaps.

A clean configuration is preferred when practicing power-on stalls, allowing the aircraft to stall more quickly.

Stalling with a high-power setting takes more effort since there is thrust and a high-energy slipstream from the propeller, which prevents boundary layer separation. This increases the effective pitch angle of the stall when compared to a power-off stall.

As a result, a power-on stall is nerve-wracking for student pilots because it features a very high pitch angle, especially with full engine power.

The idea behind this maneuver is to show that the aircraft can be stalled when you least expect it and how to recover from a dangerous situation.

Recognizing the Signs of a Power-on Stall

An aircraft doesn’t stall out of the blue. There are very obvious indications the pilot receives of an impending stall.

Reduced Airspeed

Power-off stall occurs at low airspeed. So, the airspeed slowly bleeds off as the aircraft’s pitch angle increases. Remember that an aircraft will stall at Vs with flaps up and Vso with full flaps.

High Pitch Attitude

As power is available during a power-on stall, the pitch attitude will be much higher than that of a power-off stall. The slipstream from the propeller will energize the airflow over the wing. Then the slipstream prevents boundary layer separation, allowing for a higher pitch attitude than a power-off stall.

Stall Warning Horn

The most obvious sign of a stall is the aural warning produced by the stall warning horn at high angles of attack.

The horn activates due to the change in pressure at the wing’s leading edge. It is not dependent on airspeed or altitude and is a surefire indication of an impending stall.

The stall warning horn might not activate if debris, bugs, or ice blocks the opening. You should always test the stall warning system on the ground to ensure it works.

Buffeting

Buffeting occurs when the boundary layer begins to separate from the wing surface. The turbulent air hits the horizontal stabilizer, which causes a vibration that can be felt throughout the aircraft.

Buffeting is like flying in rough, choppy air. You should be able to identify buffeting when flying to prevent the impending stall.

Poor Control Feel

When the aircraft approaches a stall, the boundary layer separates from the wing. It starts to separate from the trailing edge to the leading edge and from the wingtip to the wing root.

The lack of airflow over the ailerons results in a loss of control authority and mushy and ineffective controls. This applies to the elevator as well.

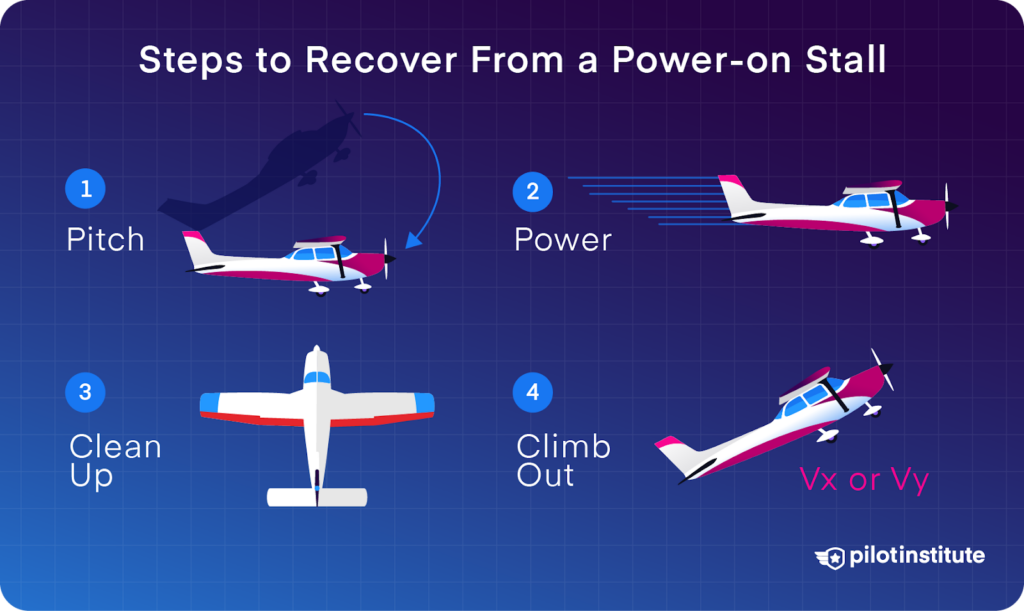

Steps to Recover From a Power-on Stall

Practicing power-on stalls can be daunting for students. The combination of a high-pitch attitude and low visibility can make you feel uneasy.

To get over this feeling, make sure to practice the maneuver often with your instructor. If you’re uncomfortable, ask your instructor to demonstrate the maneuver to get used to it.

1. Lower the Nose (Pitch)

Getting the wing flying again is the key to recovering from any stall. To do this, we have to reduce the angle of attack to less than the wing’s critical angle.

Simply put, you must reduce the aircraft’s pitch attitude by reducing backpressure on the controls.

Remember that when recovering from a stall, we want to limit the loss in altitude. As a result, you only have to reduce the angle of attack to increase airspeed, not pitch down completely. Aim to get the nose level with the horizon. This pitch attitude will allow the airspeed to increase smoothly.

2. To the Firewall (Power)

Quick and smooth power application is also required to minimize altitude loss during stall recovery. Depending on your stalling configuration, you may already be at full throttle. If so, you don’t need to worry about this step.

If you stalled with less power, add full power after reducing the angle of attack.

Watch out for torque effect (especially if you are in high-powered aircraft) since the increase in power can cause the nose to yaw to the left. This requires rudder input to maintain directional control.

It’s important to get the best performance from the aircraft possible when recovering from any stall.

3. Clean Up

Setting your aircraft up in the best configuration possible for a climb is important. While takeoff flaps improve performance, they also add unwanted drag. So, as soon as airspeed stabilizes and you’re at a positive rate of climb, gradually retract the flaps.

Be careful because retracting the flaps causes the center of the lift to move forward. This causes a pitching moment in certain aircraft. Also, retracting the flaps increases stall speed, so you could go into a secondary stall if you’re not careful.

4. Climb Out

Once you lower the pitch attitude and are at full power, focus on increasing your airspeed to Vx or Vy while maintaining attitude. Then climb at your chosen speed to return to your previous altitude, and voila! You’ve successfully recovered from a power-on stall.

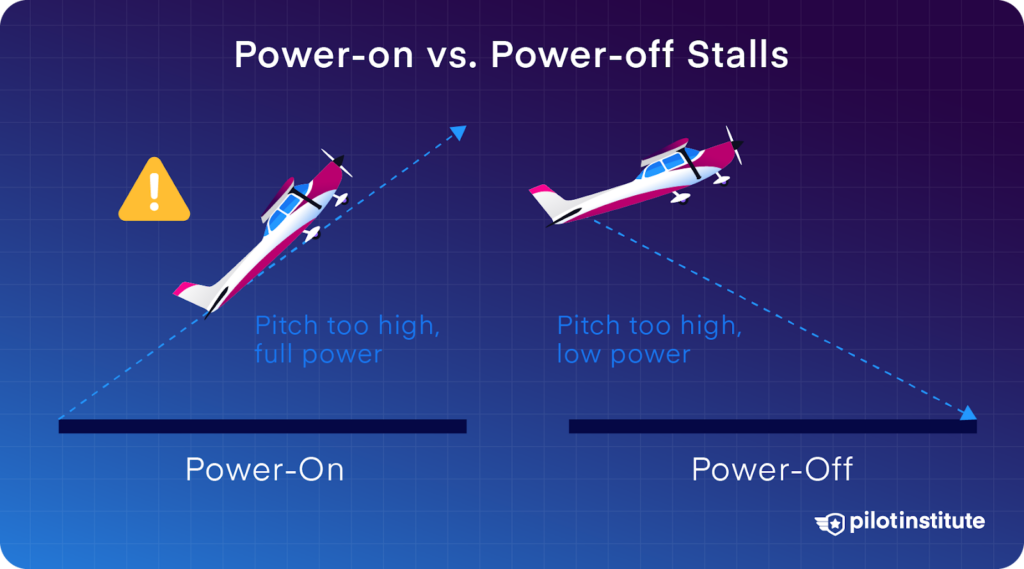

Differences Between Power-on and Power-off Stalls

Power-on and power-off stalls are very different. Power-on stalls emulate inadvertent stalls during takeoff, departures, and go-arounds. But, power-off stalls represent the landing phase of the flight.

Power Setting

The power setting is the main and most obvious difference between the two stalls. You will have at least 65% power throughout the stall process in a power-on stall. In a power-off stall, no power is available until the nose drops.

Configuration

During the power-on stalls, you will most likely be in a clean configuration or have only a single notch of flaps. But, for a power-off stall, you will be in a landing configuration with the greatest possible flap setting, which leads to extra steps during the recovery.

Recovery

We discussed the recovery process for a power-on stall above. The main difference between it and the recovery procedure for a power-off stall is the immediate and smooth addition of full power, which must be done while simultaneously reducing the pitch.

Furthermore, you must immediately remove one notch of the flaps to reduce the wing’s drag. Then, steadily clean up as the recovery goes on.

For example, in a C172, you would clean up as follows:

- Immediately after adding full power, reduce flaps from full to 20 degrees.

- As the aircraft stabilizes at level attitude, reduce flaps to 10 degrees.

- Reduce flaps to 0 when transitioning to level flight.

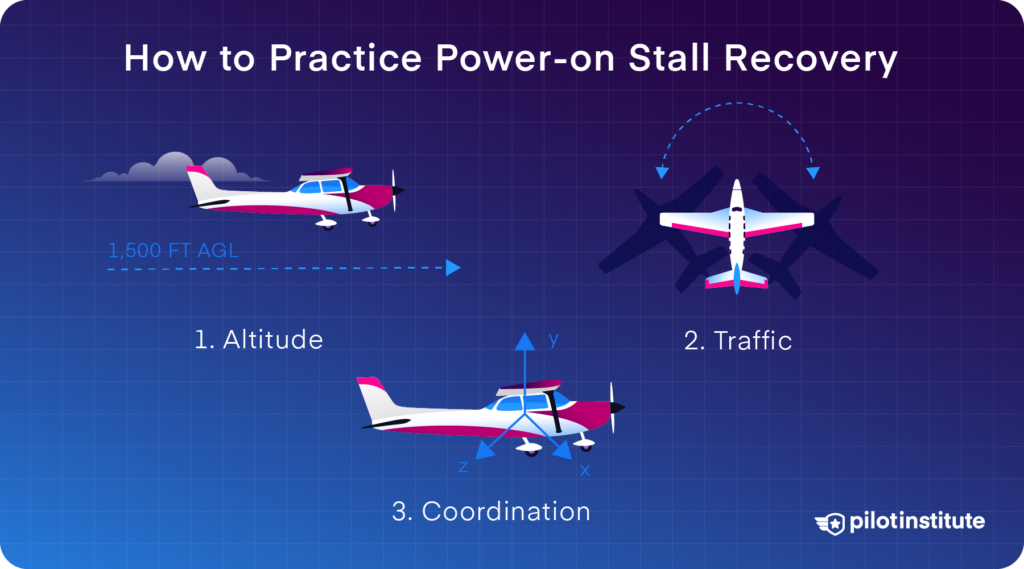

How to Practice Power-on Stall Recovery Safely

There are many safety considerations to consider when performing any kind of stall. Here are the main ones you should focus on.

Altitude

Whenever you perform a stall, always ensure that there is enough altitude for you to recover. The FAA recommends that stalls should be practiced no lower than 1,500 ft AGL. This figure is for single-engine airplanes, it could be higher for multi-engine airplanes.

You should always check the AFM or POH to see what altitude your aircraft manufacturer recommends for stall practice. Different aircraft lose different altitudes during a stall.

You should also consider the possibility of an inadvertent spin during stall recovery. An aircraft can lose up to 2000 ft of altitude in a one-turn spin and recovery. So, it’s better to err on the side of caution when choosing an altitude at which to perform a stall.

Traffic

Before performing a practice maneuver, always ensure that you are clear of traffic in the area. Check the UNICOM frequencies of nearby airports, and if your aircraft is equipped with ADS-B, use it.

Visually check for traffic before each maneuver by performing either one 180-degree or two 90-degree clearing turns.

Coordination

The last and most important safety factor to consider is coordination. Ensure that the aircraft is coordinated during stall and recovery. This is especially important at high pitch attitudes and when adding power.

The left-turning tendencies of single-engine aircraft can lead to a spin, which can be deadly if not corrected.

Conclusion

Recovering from a power-on stall can seem scary at first. But, after a few practice attempts, you’ll see it’s simple.

Just remember: reduce that angle of attack. Get those wings flying again.

By adding power and leveling out, you’re back on track before you know it. The more you get used to the process, the more confident you’ll feel when flying, even in dicey situations.

Next time you feel the airplane start to lose lift, you’ll know exactly what to do.

You’ve got this.