Let’s imagine that you are the pilot of an upgraded Cessna 421C. You are flying with friends on what should have been a simple trip from Texas to Florida.

You’ve checked the weather and planned your route. You’re confident in your skills and the advanced tools in your aircraft.

But then you start noticing something troubling—there are storms on the horizon, and they’re heading your way faster than expected.

It doesn’t take long for the situation to spiral out of control. Now, as you fight turbulence and radio for help, you must make life-or-death decisions.

This is the true story of N4467D and its ill-fated encounter with severe weather. This is a story that teaches us a lesson about the balance between technology and human factors in every flight.

Key Takeaways

- Weather can change faster than your technology can show.

- Good decision-making is more important than pushing through dangerous conditions.

- Weather tools are helpful, but you can’t rely on them alone.

- ATC advice is valuable, but as a pilot, you are responsible for your flight’s safety.

- View the NTSB accident report here (PDF download).

The Flight and Weather Concerns

The date is July 8, 2009, and the day was already hot by mid-morning in McKinney, Texas.

Five eager passengers boarded a sleek, upgraded Cessna Golden Eagle, which was the pride of the company fleet.

The pilot had already filed an IFR flight plan to Tampa, Florida, and reviewed the weather reports.

Thunderstorms loomed in the distance. But with his well-equipped aircraft, the pilot felt more than confident that he could navigate through this weather easily.

Besides, he had handled storms before, and his equipment provided him with the real-time data he needed to stay out of harm’s way—or so he thought.

At first, everything went well.

For over two hours, N4467D glided effortlessly through the skies. But then, as they approached the Florida panhandle, the weather ahead started to worsen.

The pilot informed ATC that he might need to deviate around the storms. ATC reassured him. They said the storms weren’t as bad as they looked. And they told him that other airplanes were making it through without trouble.

This put the pilot at ease.

But what the pilot didn’t know was that the worst of the weather was still ahead.

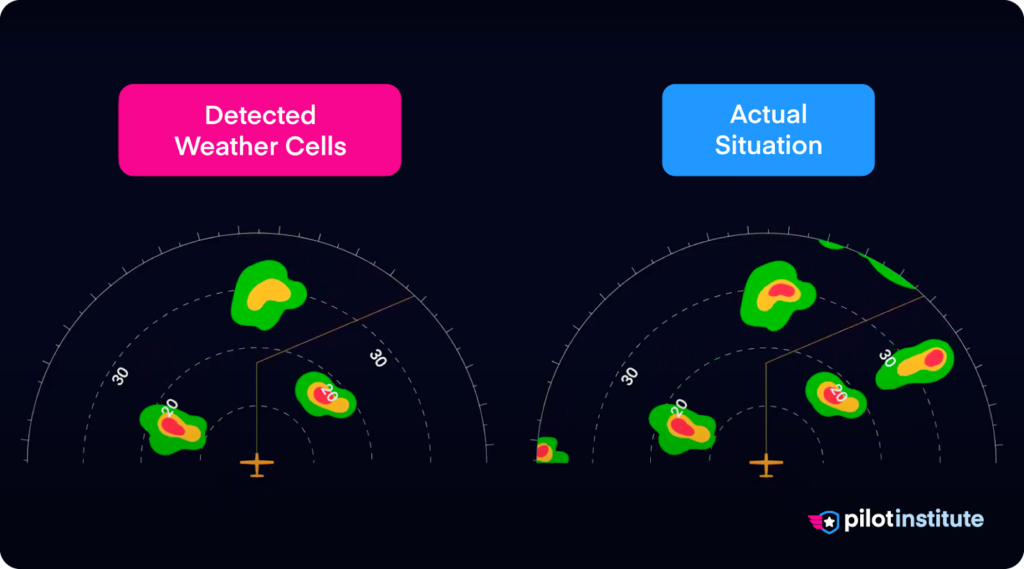

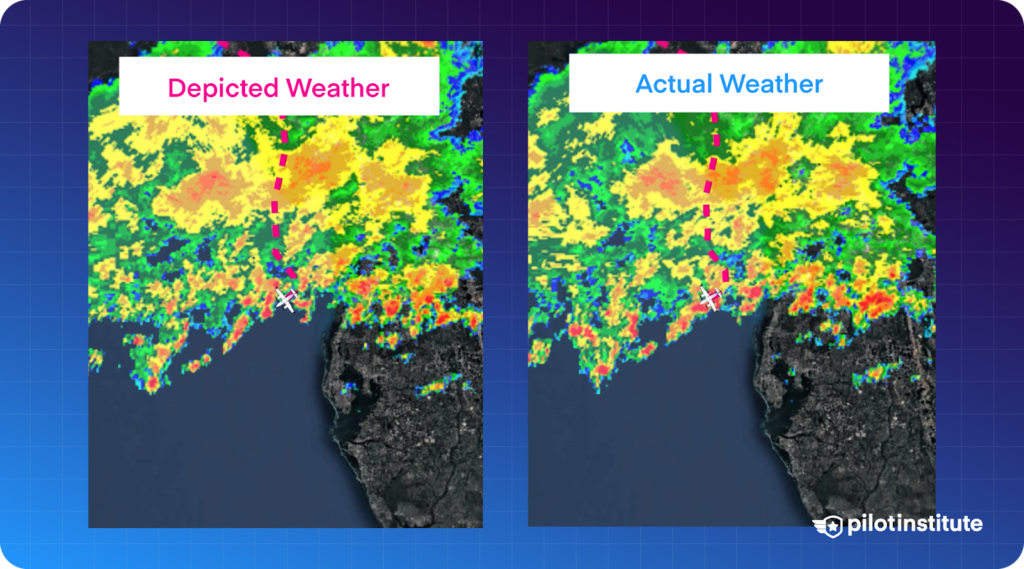

A massive storm cell was heading his way. His XM Weather showed an orange or red zone. But, its delay meant the true intensity of the weather was not yet visible on his screens.

Technological Factors in Aviation Weather Monitoring

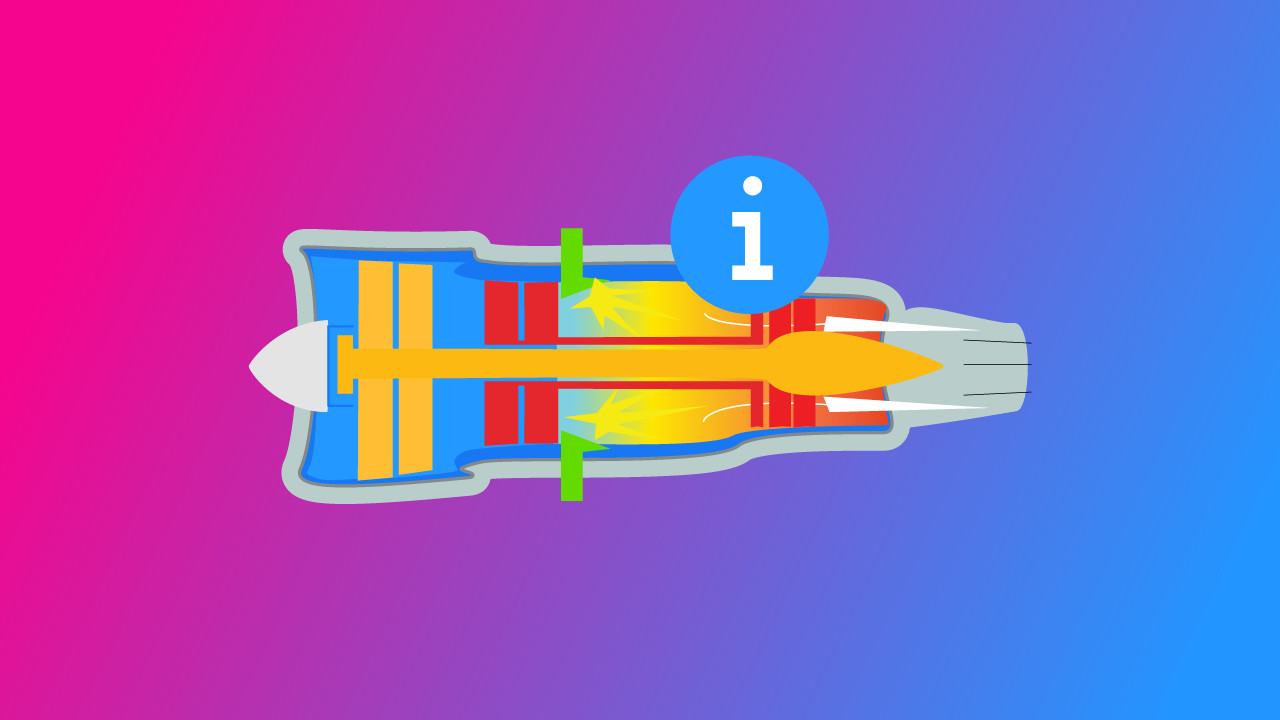

N4467D was a modern airplane. It had advanced weather tools, like a radar, Stormscope, and XM weather satellite receiver. And while these fancy things were helpful, they had limitations the pilot may not have appreciated.

Onboard radar can show precipitation, color-coded by intensity. But, it can also be incredibly deceptive.

Precipitation attenuation occurs when heavy rain weakens the radar signal. And in the case of N4467D, it made the storm seem less intense than it was.

Radar shadows are blind spots created by dense storms. They can give pilots a false sense of security about what lies ahead of them.

And even when radar is accurate, it’s most reliable within 40 to 80 miles. Beyond that, its accuracy starts to diminish.

The XM weather system on board N4467D made things even more complicated. It provided aviation weather updates. But, they could be up to 15 minutes behind the real-time conditions.

In aviation, a lot can change in 15 minutes, especially in a fast-moving storm.

The pilot’s XM system showed moderate to heavy rain. But, by the time he flew into it, the storm had grown far more dangerous than the technology could relay to him.

Decision-Making Under Pressure

Even with these advanced tools at his disposal, the human element was the biggest part of this unfolding disaster.

The pilot had seen other aircraft navigate the storm. So, he may have been influenced by expectation bias, which is within the scope of a hazardous attitude to have as a pilot.

He believed that if others could get through the storm, so could he.

N4467D was a Cessna 421C, not a large airliner. It didn’t have the same ability to withstand the forces of extreme weather.

Then, there’s “get-there-itis.” The pilot had a strong urge to finish the flight because of the pressing obligations.

Diverting would have been a safe(and wise) choice, but it would have also been an inconvenience. For a pilot flying colleagues and friends, turning back or saying “unable” to ATC might have felt like admitting defeat.

ATC itself also attributed to the situation. Though the controllers tried to guide the pilot safely, one decision proved fatal. When the pilot reported severe turbulence, ATC suggested turning around.

The course reversal pushed N4467D into the storm’s heart. And this decision would ultimately lead to disaster.

The Fatal Chain of Events

At 2:41 PM, just 50 miles from Tampa, the aircraft encountered severe turbulence.

The pilot requested help from ATC. They advised him to continue straight ahead, where they saw clear skies.

Moments later, the pilot made a chilling report: he was losing control. The aircraft began a rapid descent, and ATC suggested turning around.

But it was too late. Just seconds later, the pilot radioed a desperate mayday call:

“We’re upside down!”

Radar contact was lost, and the aircraft broke apart mid-air. All five souls on board were lost.

What Can Pilots Learn From This Case?

The tragedy of N4467D teaches us the importance of balancing technology with good decision-making skills as a pilot.

Yes, weather tools are valuable, but they are not infallible. Pilots must know their equipment’s limits and they must always prioritize safety, even when under pressure.

When flying into adverse weather, knowing when to divert or say “unable” to ATC can save lives. A well-planned deviation or an early decision to land instead could prevent accidents like this from happening.

Technology and instruments should assist, not replace, good decision-making and situational awareness.

Conclusion

The NTSB determined that the accident of N4467D was a tragic case of human error. This was made worse by the pilots’ technology’s limits.

The pilot relied on old weather data and the advice of controllers who didn’t fully grasp the severity of the situation.

The result was an in-flight breakup that sadly claimed the lives of all onboard.

For all pilots, the lesson is this: don’t push the limits of what your aircraft and its technology can do.

Know when to divert, when to question your tools, and most importantly, when to put the safety of human life above all else.

Fly safely fellow pilots, and always remember that no flight is worth the risk of cutting corners.